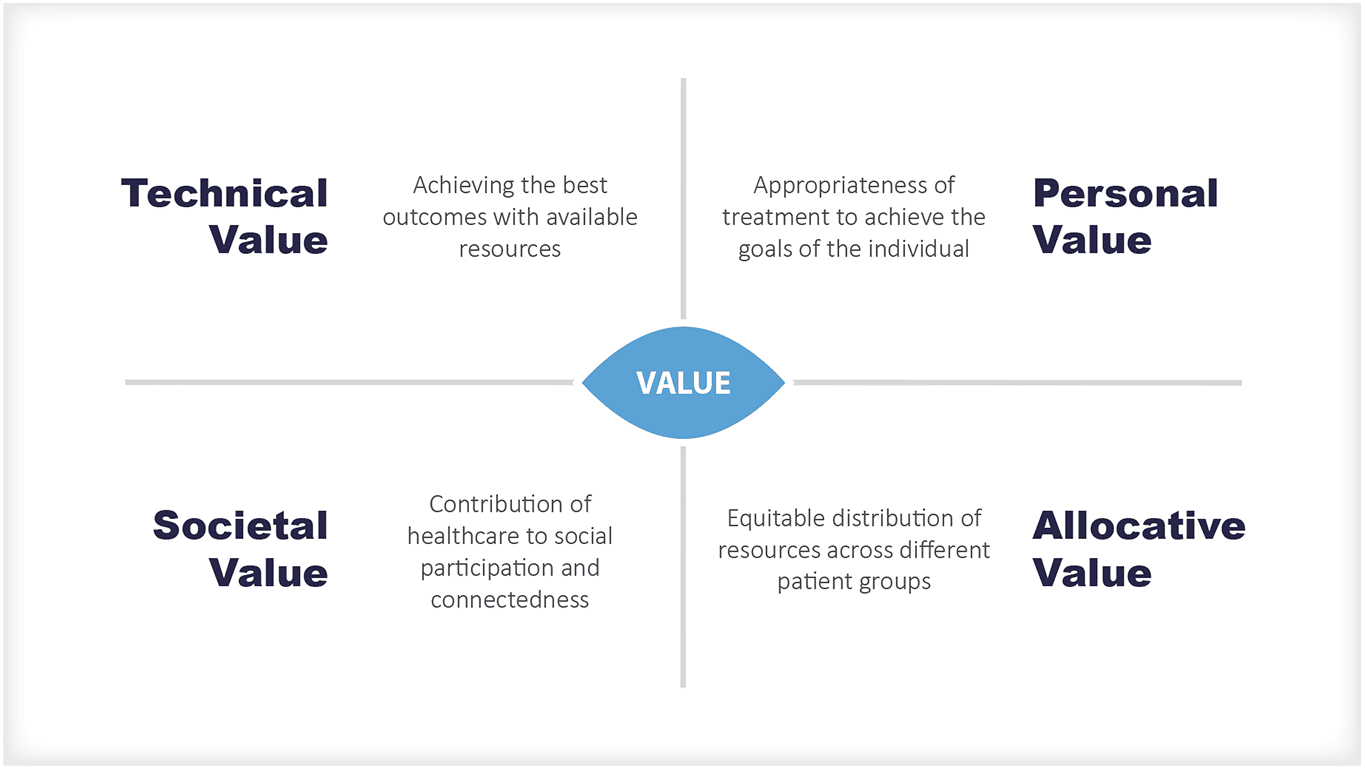

When setting health system goals, let’s think beyond the value based healthcare triple aim and look at personal value, technical value, allocative value, and societal value.

Market Pricing

Economists generally think the value of a good or service is synonymous with the market price. In traditional, neoclassical economics, markets are an efficient way of allocating resources between buyers and sellers. Goods and services are traded using a common medium of exchange, usually a currency. In general, markets work well when:

- Individuals behave rationally

- There is a balance of information between the buyer and the seller – perfect information

- Resources are mobile, allowing suppliers and customers to enter or exit the market with ease

- There is choice for both consumers and suppliers

- The good or service can be uniquely consumed by the customer (it is not a public good)

- The value is limited to the buyer and seller (there are no externalities).

In this model, the market price for a good or service reflects the point at which its value to consumers equals the value to suppliers. All other things being equal, this is also the value to society. Lovely. In theory.

Anyone who has read Doughnut Economics by Kate Raworth will see how these basic constructs can be challenged [1]. Not least the concept of a rational individual. The work by Ehsan Masood on why GDP measurement needs to change re-enforces the issue that economic success is not just about valuing those goods and services that have a market price [2].

Healthcare Markets

In healthcare, markets fail badly. Really badly. In fact, pretty much all of the conditions for unregulated markets to be efficient at allocating resources fail. Taking each of the six points of failure shown earlier it is easy to show where the problems lie:

- Health is a fundamental human right indispensable for the exercise of other human rights (OHCHR)

- The Doctor – Citizen knowledge relationship is asymmetrical and complex

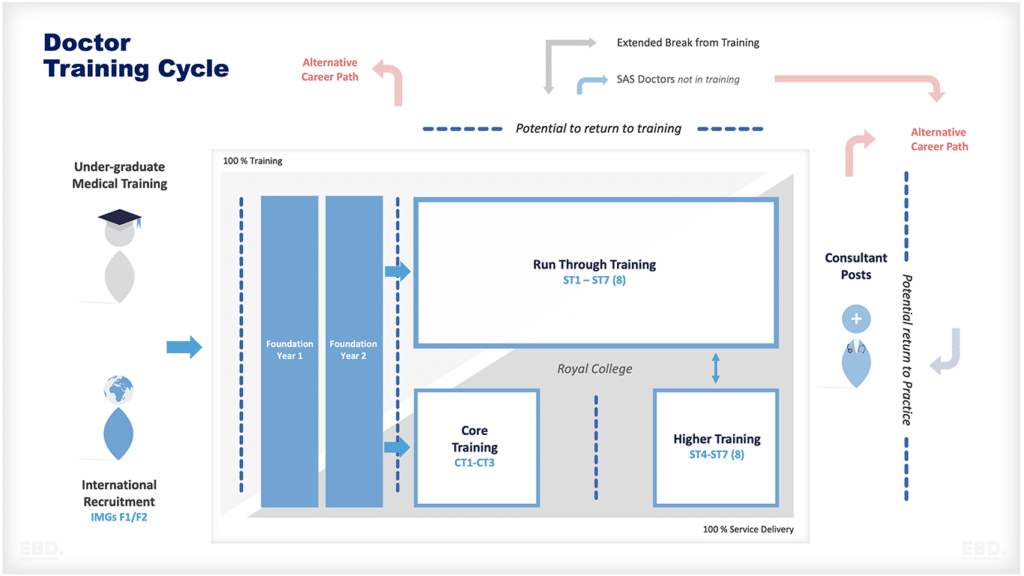

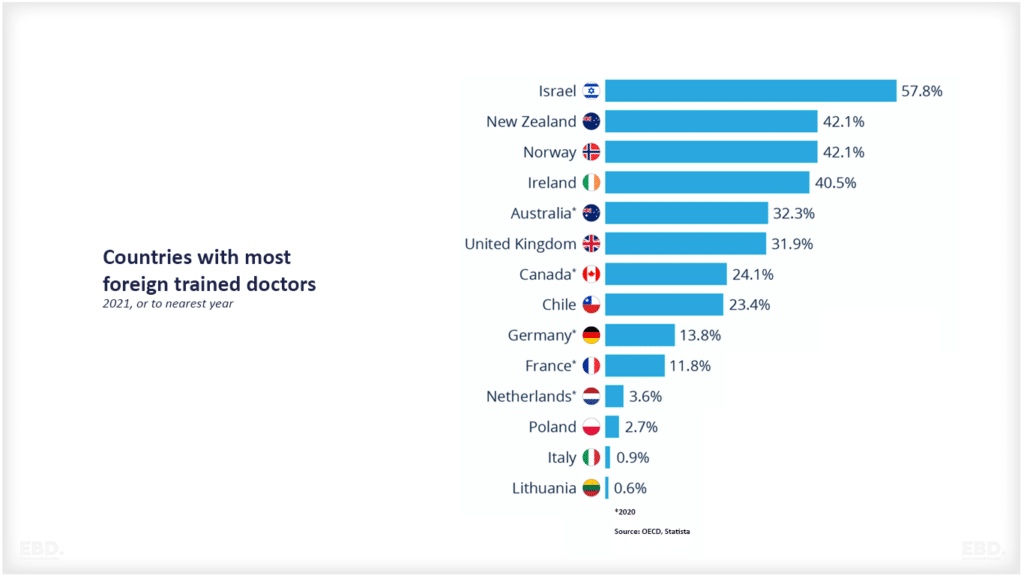

- It takes >15 years to train a doctor, hospital infrastructure is expensive, inflexible and immobile, pharmaceutical investment is high risk and takes time

- Economies of scale in health, especially secondary care services, restrict choice for consumers except in large cities

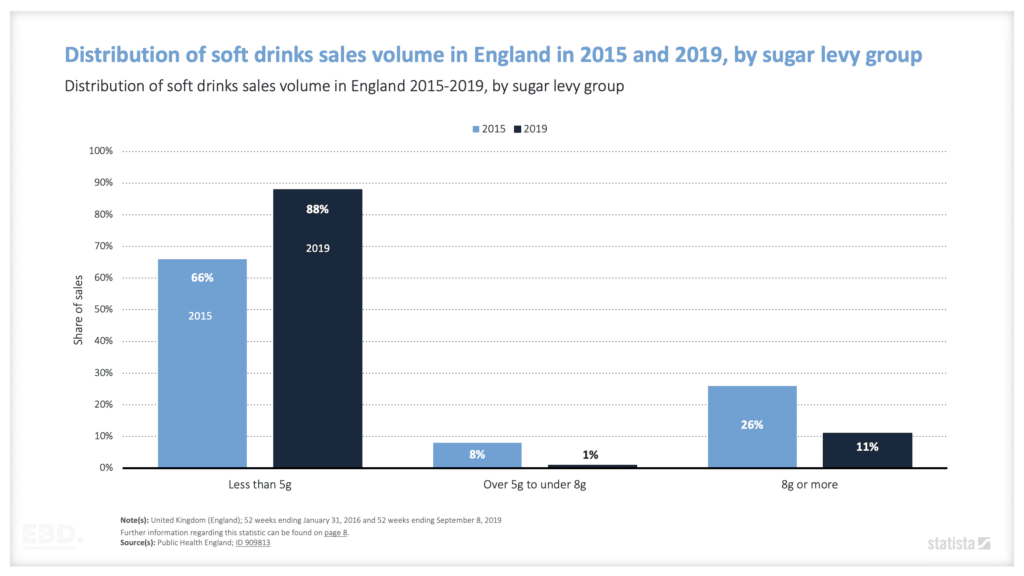

- Prevention services are often public goods (think clean air, clean water, community vaccination)

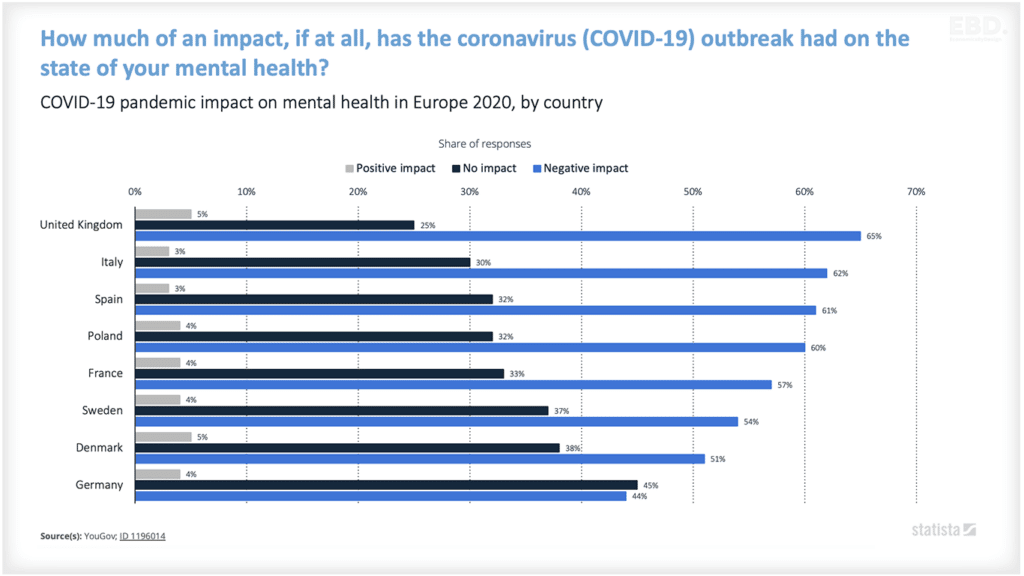

- Poor health impacts on society not just individuals (think COVID-19).

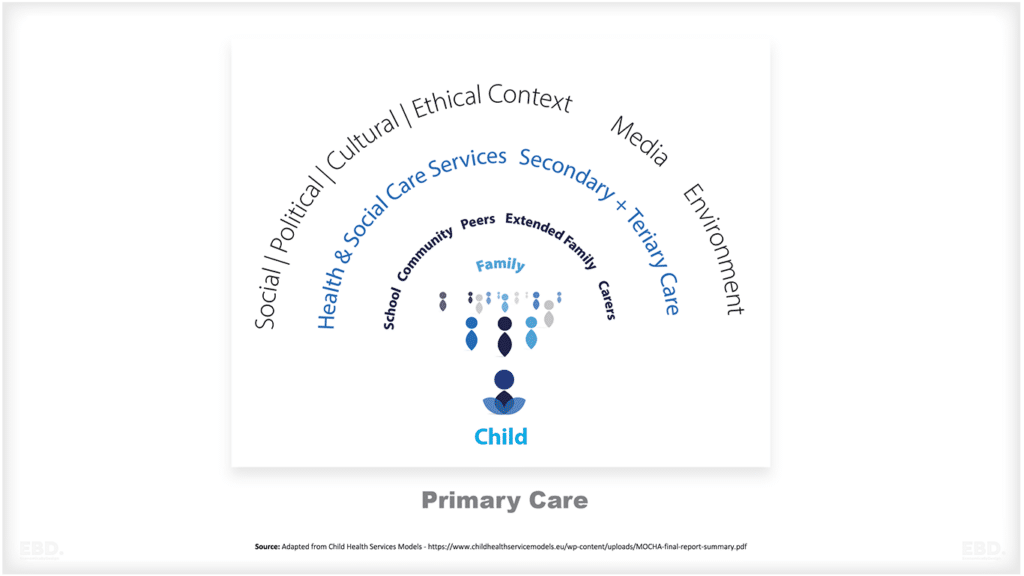

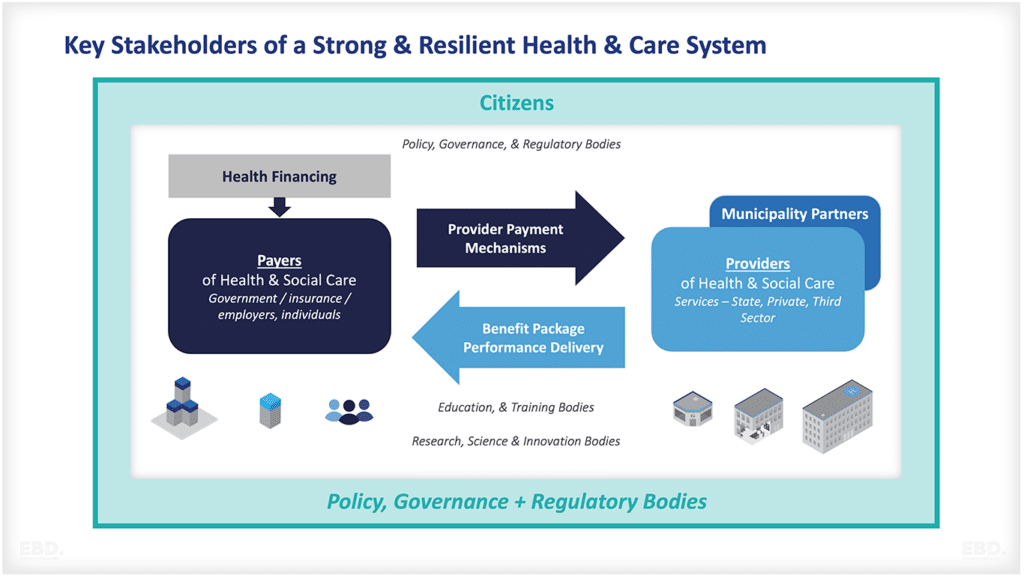

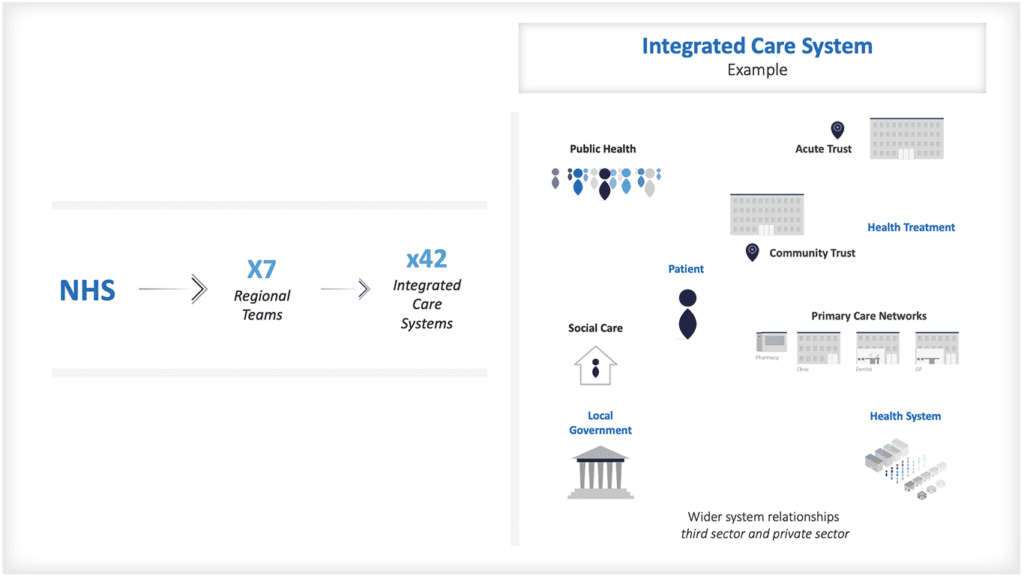

This is why we have major international initiatives such as Universal Health Coverage, and Integrated People-Centred Health Services [3]. They are there to guide governments as to how to support healthcare systems to maximise value for citizens and society as a whole.

So, what happens when we can’t rely on market price as a measure of societal value. Where there isn’t even a price to reference?

Value Based Healthcare

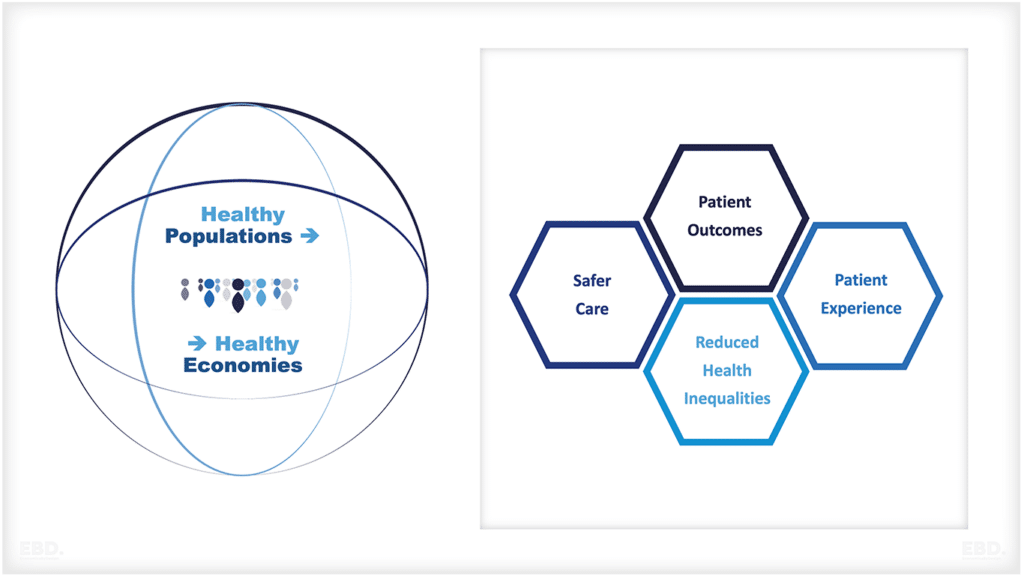

Talk to many colleagues in the health service about measuring the value of healthcare and they will mention “value-based healthcare”. Often, they will reference the triple aim of improving population health, the experience of care, and reducing the per capita cost of care [4]. Some have added the experience of staff delivering care to make it the quadruple aim [5].

However, the European Commission has a broader definition of value-based health care. The European Expert Panel on effective ways of investing in health identified four dimensions of value:

Technical Value

Achieving the best outcomes with available resources

Personal Value

The appropriateness of treatment to achieve the goals of the individual

Allocative Value

Which is about equitable distribution of resources across different patient groups

Societal Value

Which is about the contribution of healthcare to social participation and connectedness [6]

Health economics can help put some additional perspectives to this framework. Health economists are well known for looking at health system technical efficiency. You only need look as far as health technology appraisal to see that.

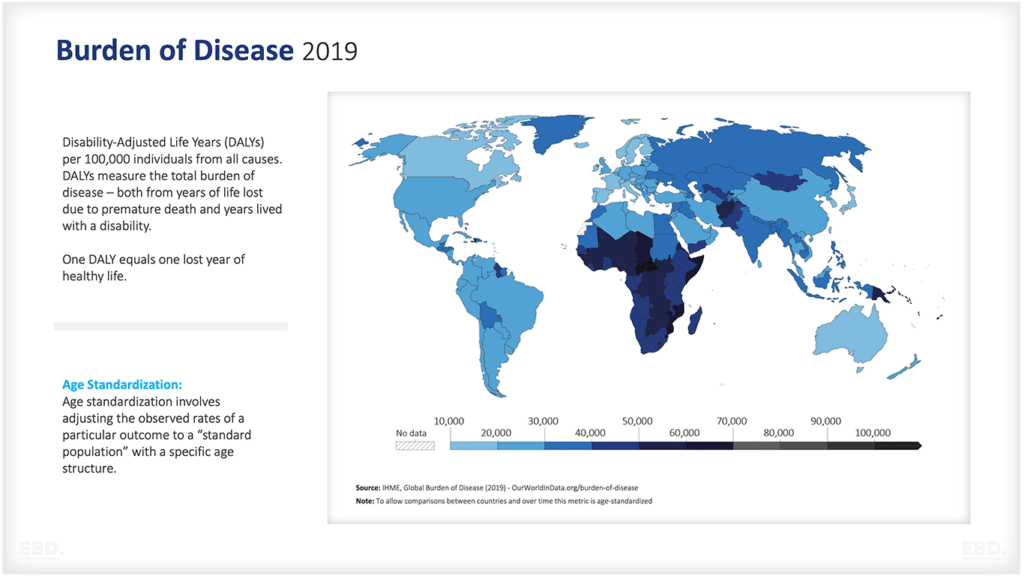

Health economists have also devoted considerable efforts to developing ways of measuring health and social care outcomes [7]. Think of DALYs and QALYs.

Recently economists have built on this to create a value of personal wellbeing, known as the WELLBY.

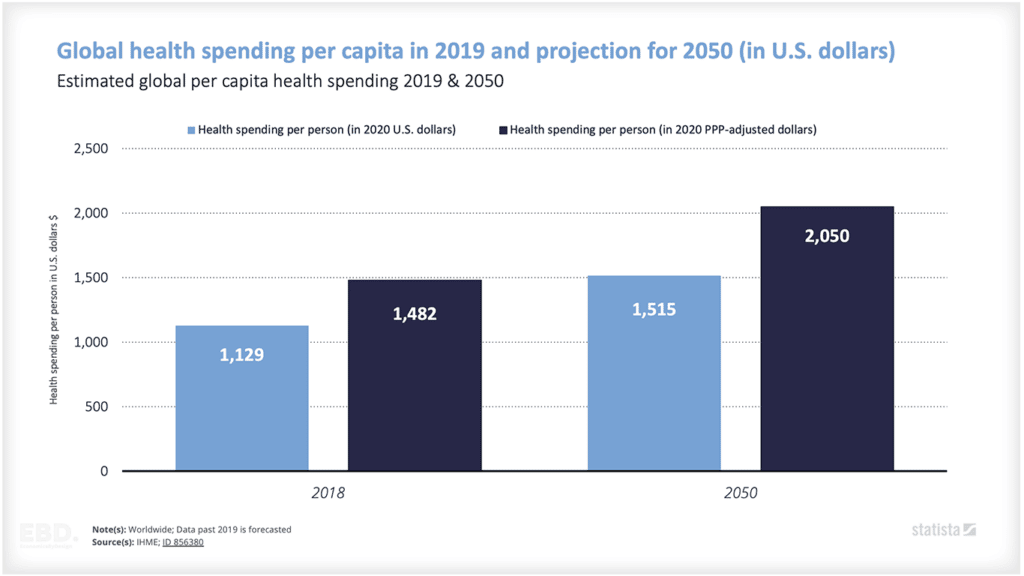

Some health economists have spent considerable time on ways of ensuring fair share allocations of resources. Consider fair-shares formulas for capitation-based payment models for strategic purchasing of health services and the extensive work that has been done to measure the cost of health inequalities [8].

Relatively recently, the economic value of the social impact of healthcare has also been a hot topic for research [9].

A final reflection then. When we think about value in healthcare, we must think beyond “price” and “markets”. We must even think beyond the triple aim, or even the quadruple aim. If goals are to be set, then let’s set consistent value goals for all four dimensions of value-based care as per the European definition.

[1] //www.kateraworth.com/doughnut/

[2] Ehsan Masood “GDP: The World’s Most Powerful Formula and Why it Must Now Change” 2021

[3] //www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/clinical-services-and-systems/service-organizations-and-integration

[4] //www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx

[5] //qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/24/10/608

[6] Source: Expert Panel on effective ways of investing in Health (EXPH) Defining value in “value-based healthcare”, European Commission, 26 June 2019

[7] There will be more to come on Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) and Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) in another blog.

[8] //www.york.ac.uk/news-and-events/news/2016/research/nhs-inequality-costs/

[9] //www.health.org.uk/what-we-do/a-healthier-uk-population/health-as-an-asset/social-and-economic-value-of-health-2019-place