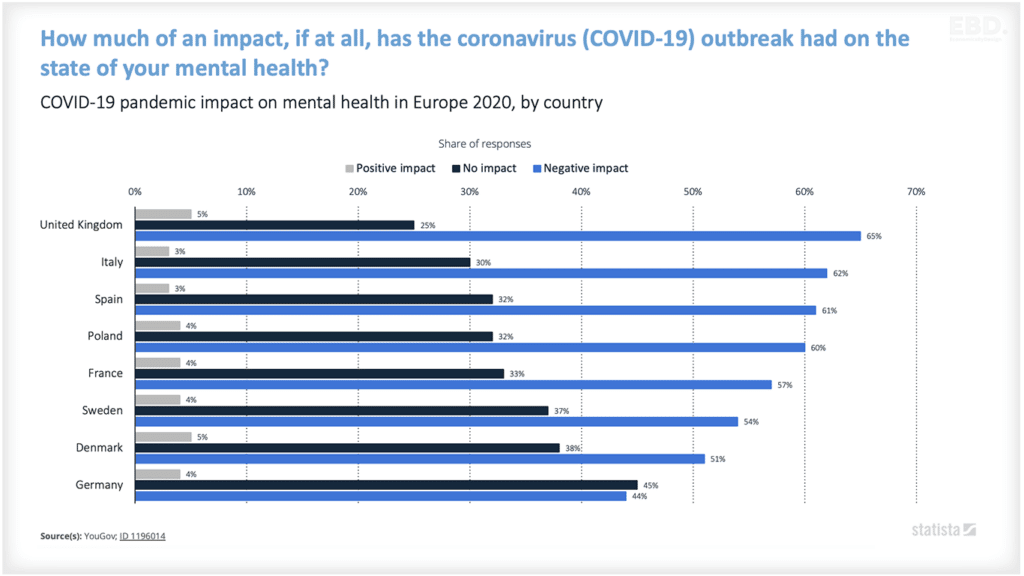

There is no one-size-fits-all answer to the question of what social care is, as the term can refer to a wide range of services and support provided to people who have difficulties with everyday tasks or who are unable to live independently. It can take many different forms, from practical help with tasks such as shopping and cleaning, to emotional support and advice.

In this economic lens we look at what social care is and who might need it, the relationship between social care and healthcare, how social care is financed, what type of organisation provides it, what happens when it is not provided or is of poor quality, and what is its potential economic value.

What is Social Care?

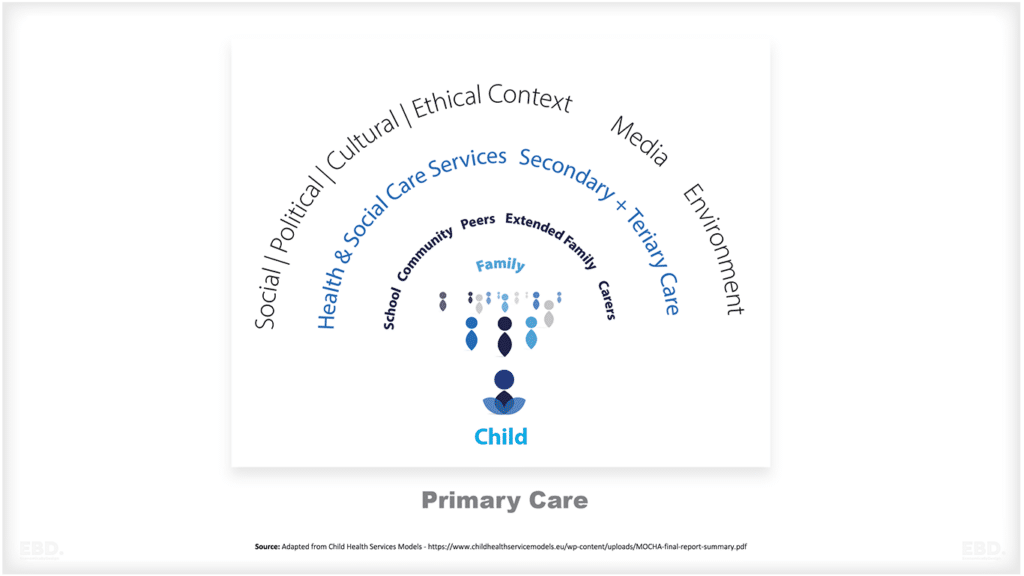

Social care can take many different forms, and the type of support that someone needs will depend on their individual circumstances. It can range from practical help with tasks such as shopping and cleaning, to emotional support and advice. It is normally provided if someone has need of practice support because they are living with an illness, often caused by a long-term health condition, or they have a disability.

Practical help can be provided in a number of ways. For example, someone who is living with a disability or long-term health condition may need assistance with everyday tasks such as getting dressed, washing, and eating. This type of support is often known as ‘personal care’, and it can be provided by a trained care worker in the person’s home, or in a residential care setting such as a nursing home. People who need help with everyday tasks may also need assistance with other practical matters such as budgeting, cooking, and cleaning. This type of support is often known as ‘domiciliary care services’, and it can be provided by a trained care worker or household help.

Social care services can also involve providing emotional support to people who are struggling to cope with a difficult life event or a long-term health condition. This type of support is often known as ‘emotional care’, and it can be provided by a trained counsellor or therapist. Emotional support can also be provided by family and friends, who may offer a listening ear and a shoulder to cry on. This type of support is often referred to as ‘informal care’, and it can be just as important as formal care in helping someone to cope with a difficult situation.

Social care services can include home adaptations, household equipment and other forms of support such as personal alarms. It can include supported housing where individuals live at home with support or in groups with support levels determined by need.

In some countries, social care services provided for people living at home are referred to as home support services and are distinct from residential care services where someone needs accommodation and 24 hour personal care and who would find it difficult to live at home.

Who Might Need Social Care Services?

Individuals of all ages might find themselves in need of social care services. Services can be provided for the benefit of children and young people, and adults of all ages (often referred to as adult social care). Services might be needed on a long-term basis due to disability or illness, or temporarily during a transient period of ill health. Some services are targeted at “reablement’ and are designed to help people to reach their maximum level of independence following a period of ill health or a stay in hospital.

What Drives Demand for Social Care?

The following drivers are important and will also vary for different countries and regions.

Demographic Trends

This include increases in numbers of people by age and gender (demand rises with age and is differential between men and women), marital status, the number of single people living with others (children, relatives, friends)

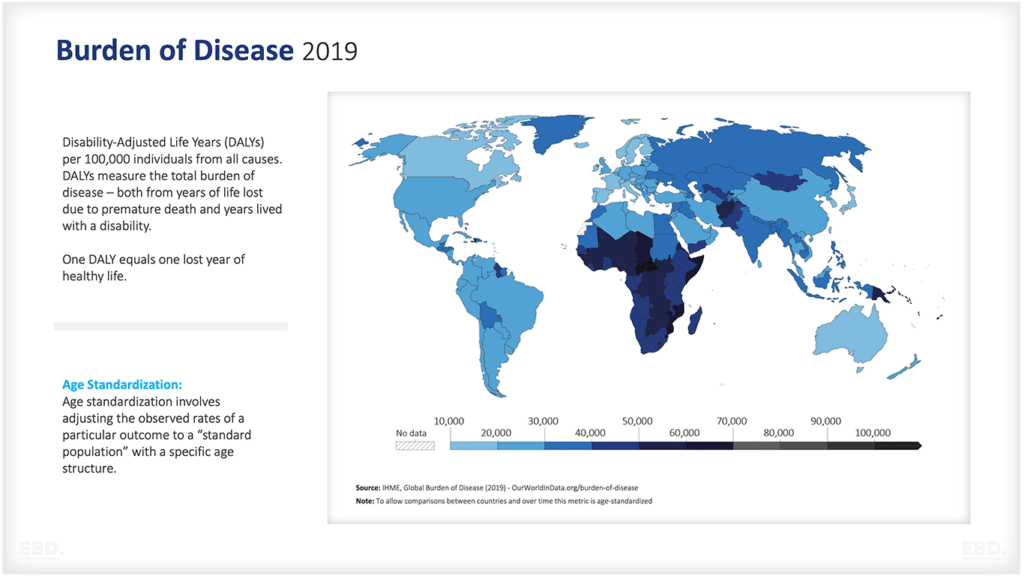

Epidemiological / Morbidity Trends

This includes increases in prevalence rates in specific age bands for disability and frailty (age specific demand is likely to rise as a result of increased chronic disease(s) risks and hence frailty risk)

Policy Interventions

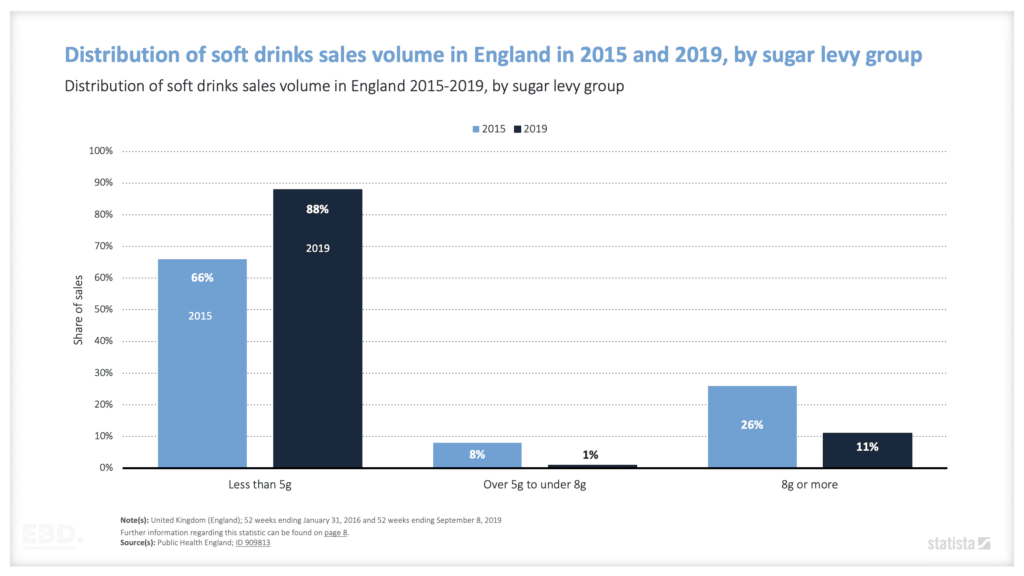

Designed to increased healthy life expectancy and disability-free life expectancy as a result of social prescribing/prevention (smoking, alcohol, diet, physical activity, air quality, water quality)

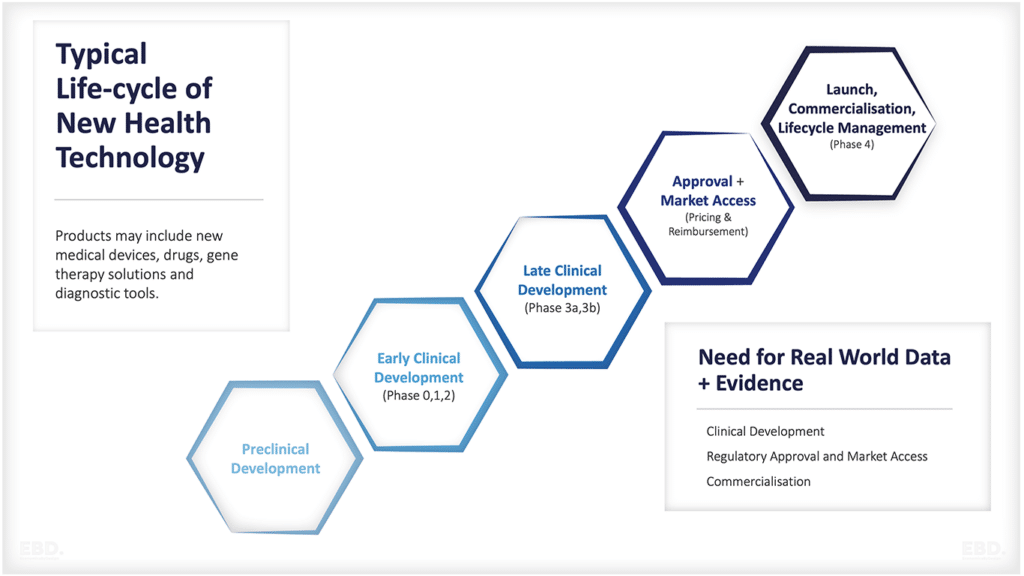

Clinical Interventions

Designed to screen, diagnose and medicate earlier to delay on-set

Supply Substitution

Effects such as the availability of informal carers – family structures, policy interventions designed to support informal care, and create community-based interventions designed around community assets, technology advances which allow closer remote monitoring of people at home by informal carers and formal carers

Economic Trends

This will include the wealth of the population and their ability to pay for private services (through insurance, family assets/savings) – often homeownership rates are used as a marker here

What Is The Difference Between Health Care and Social Care Services?

It is important to distinguish between social care and healthcare, as they are two separate but complementary services. Healthcare includes medical treatment and diagnosis, nursing care, as well as preventive measures such as vaccination programmes.

The line between healthcare and social care can sometimes be blurred, as both services often work together to support people with long-term health conditions or disabilities. For example, someone who has been discharged from hospital after treatment for cancer may need both healthcare and social care to help them recover and live as independently as possible.

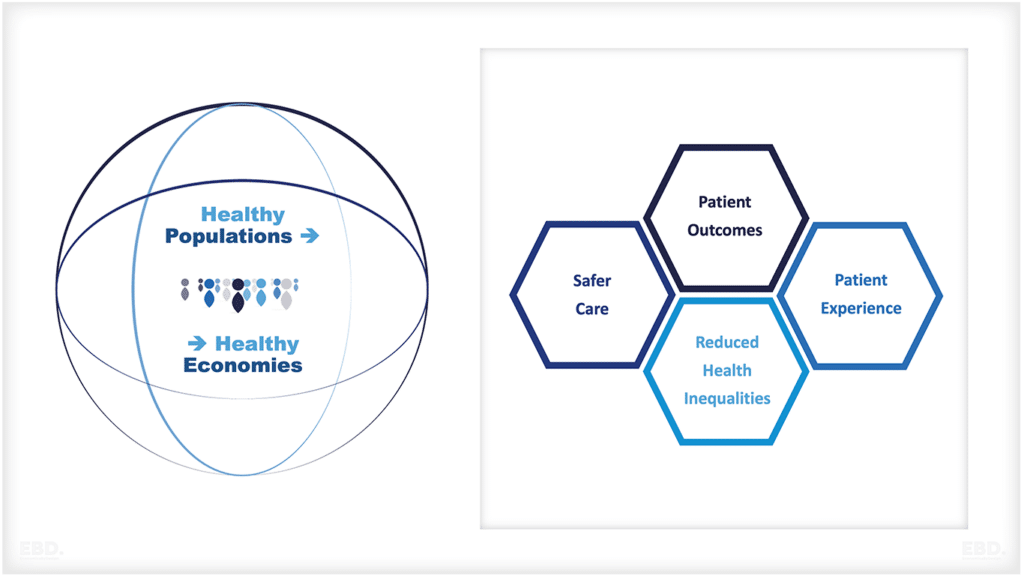

There is a growing recognition that social care is an important, if not vital, complement to healthcare, and can play a vital role in keeping people well and out of hospital.

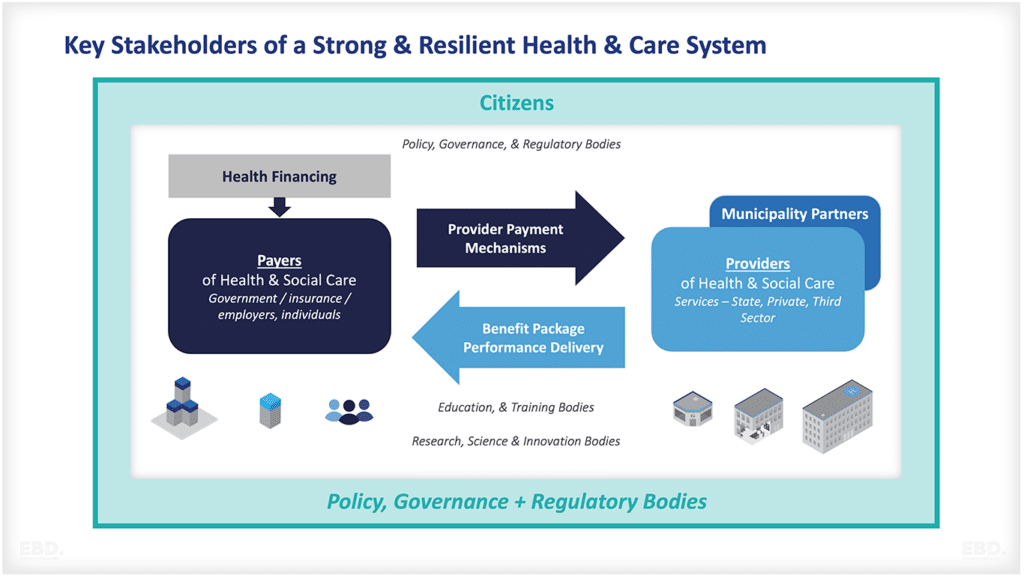

How Is Social Care Financed?

The way that social care is financed varies from country to country. In some countries, social care services are free for those who qualify, either through government funding or charitable organisations. In other countries, people may need to contribute towards the cost of their own care. Some individuals have private insurance which covers some or all of their social care needs.

In Germany, social care is funded by a compulsory long-term care insurance programme which was introduced in 1994 and has been mandatory since 2009. The schemes/funds are managed by health insurance schemes with eligibility determined by physical and cognitive dependency. Those eligible for funding can receive cash or services with services provided by any registered or accredited provider. Contribution levels and eligibility criteria are set by the Federal Government.

The Netherlands was one of the first countries to establish long term care insurance for all back in 1968. However, in 2007 and more extensively in 2015, responsibility for social care was transferred to municipalities, with community nursing care becoming the responsibility of health insurers; this was designed to retain universal health coverage whilst having more flexibility for the delivery of home care support services.

Japan is another example of a service financed by long-term care insurance. The scheme in Japan was introduced in 2000 and premiums are compulsory for those in employment who are aged over 40 years old.

In Sweden, whilst the rights to home care are enshrined in legislation, funding and eligibility is determined by municipalities / local authorities. Eligibility for support is determined on the basis of a local assessment of need and a means-test.

In England, social care services are provided by local authorities and are tightly rationed. Individuals can receive various allowances depending on their age and whether they have a disability which can help them with additional costs of needing support. Carers can also get a carers allowance. However, funding for social care services provided by local authorities are means-tested including both income and wealth (asset) tested. (9,10).

Who Provides Social Care?

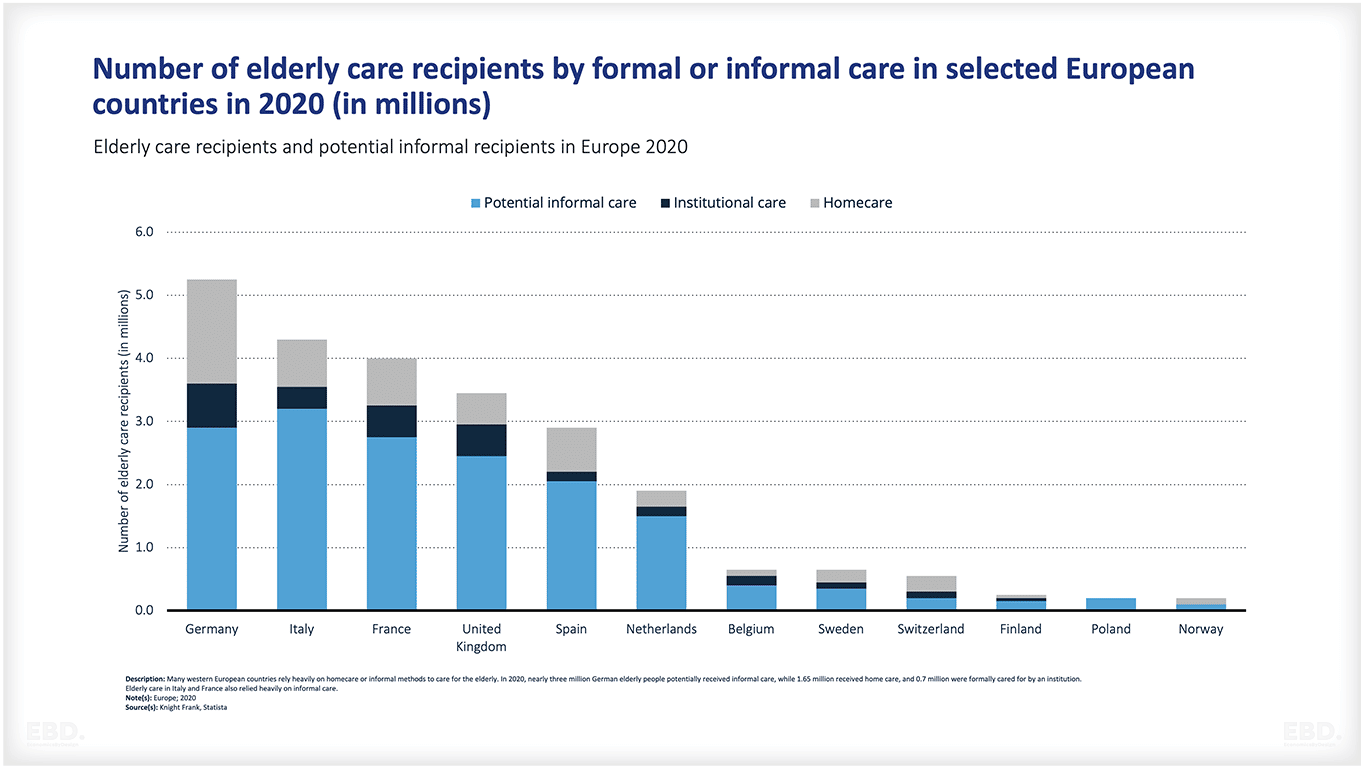

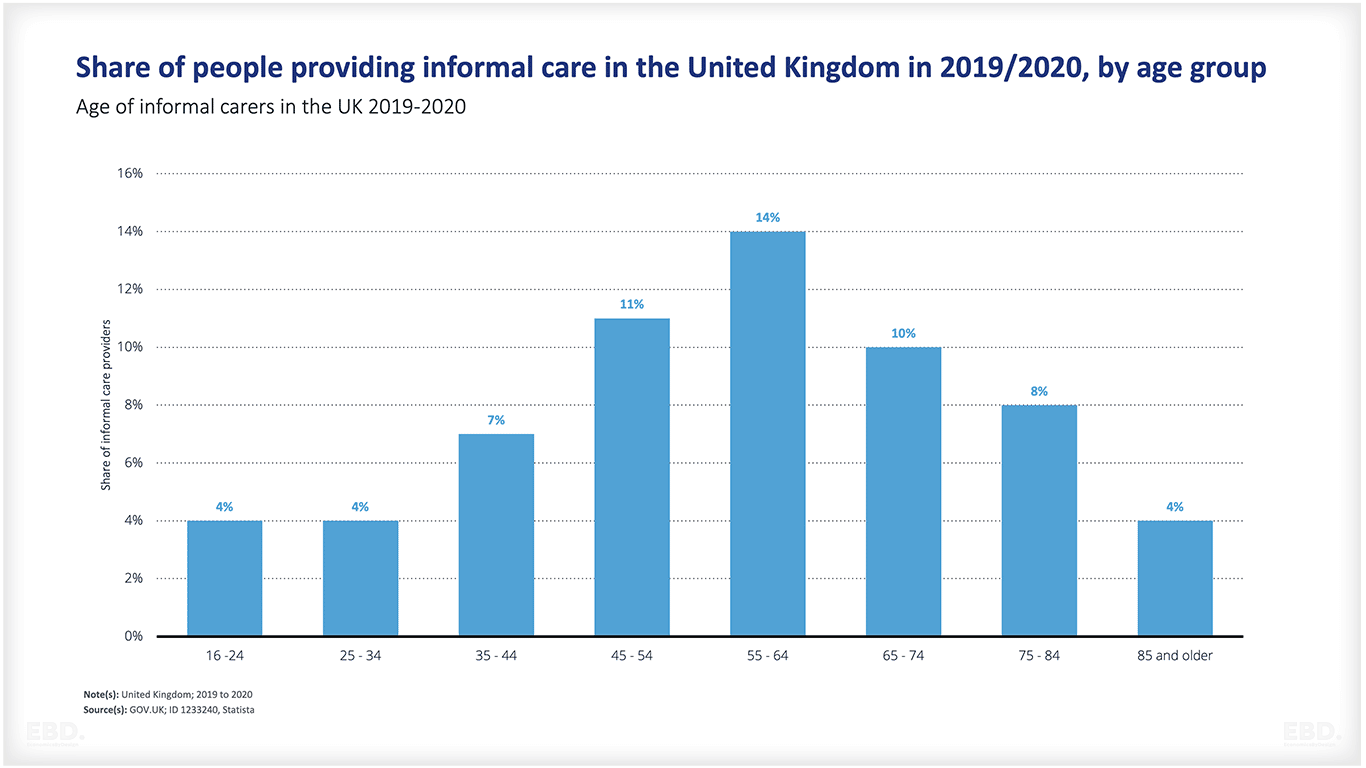

As the chart below shows, social care is very often provided in the form of informal care by family members or other informal carers with whom the individual has a social relationship.

Informal carers include both the young and the elderly; often care is provided by a child or a partner.

Formal social care services can be provided by a range of different organisations including local authorities, charities and the private sector.

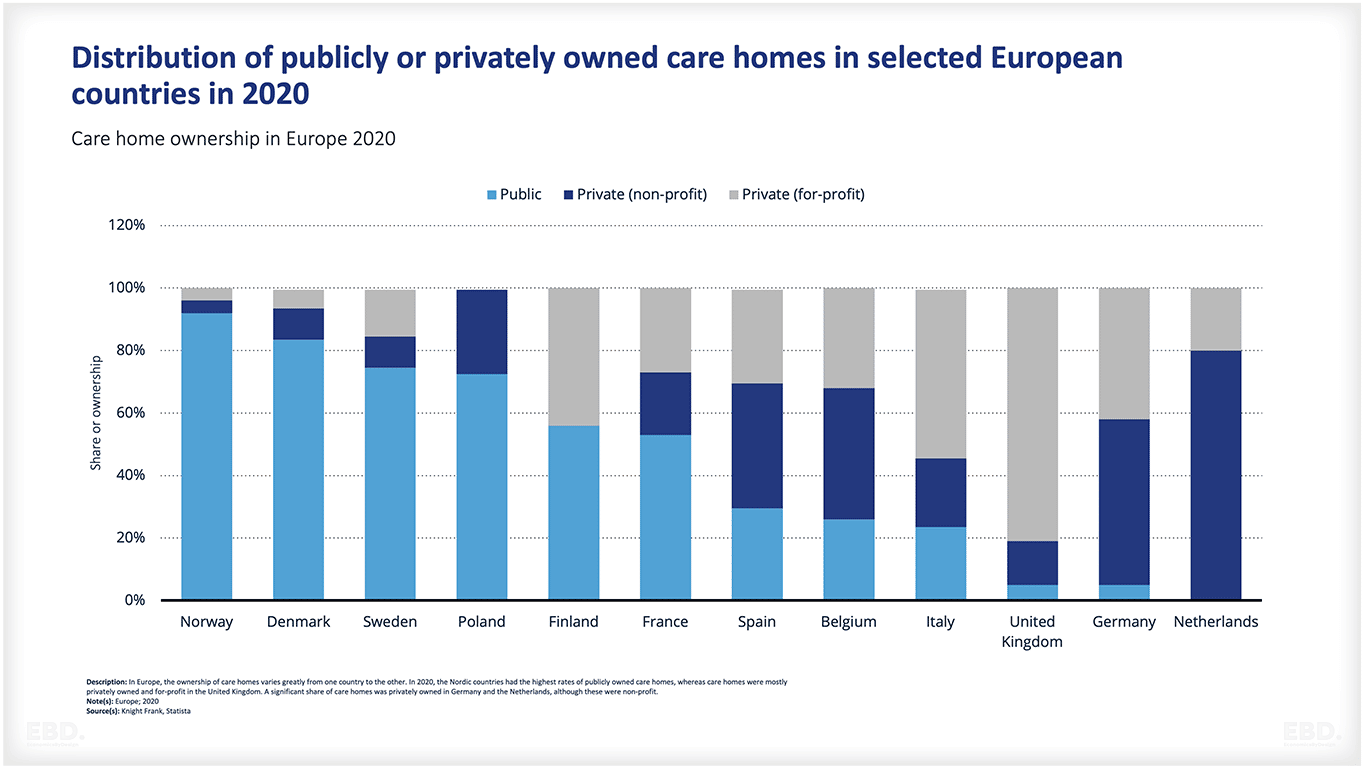

The ownership model for social care service providers varies considerably by country. The chart below shows some examples from Europe. As can be seen in the nordic countries (Norway, Sweden and Denmark), public provision is the dominant model. However in the United Kingdom the private (for profit) model dominates.

What Are The Key Challenges Associated With Social Care?

Workforce Shortages

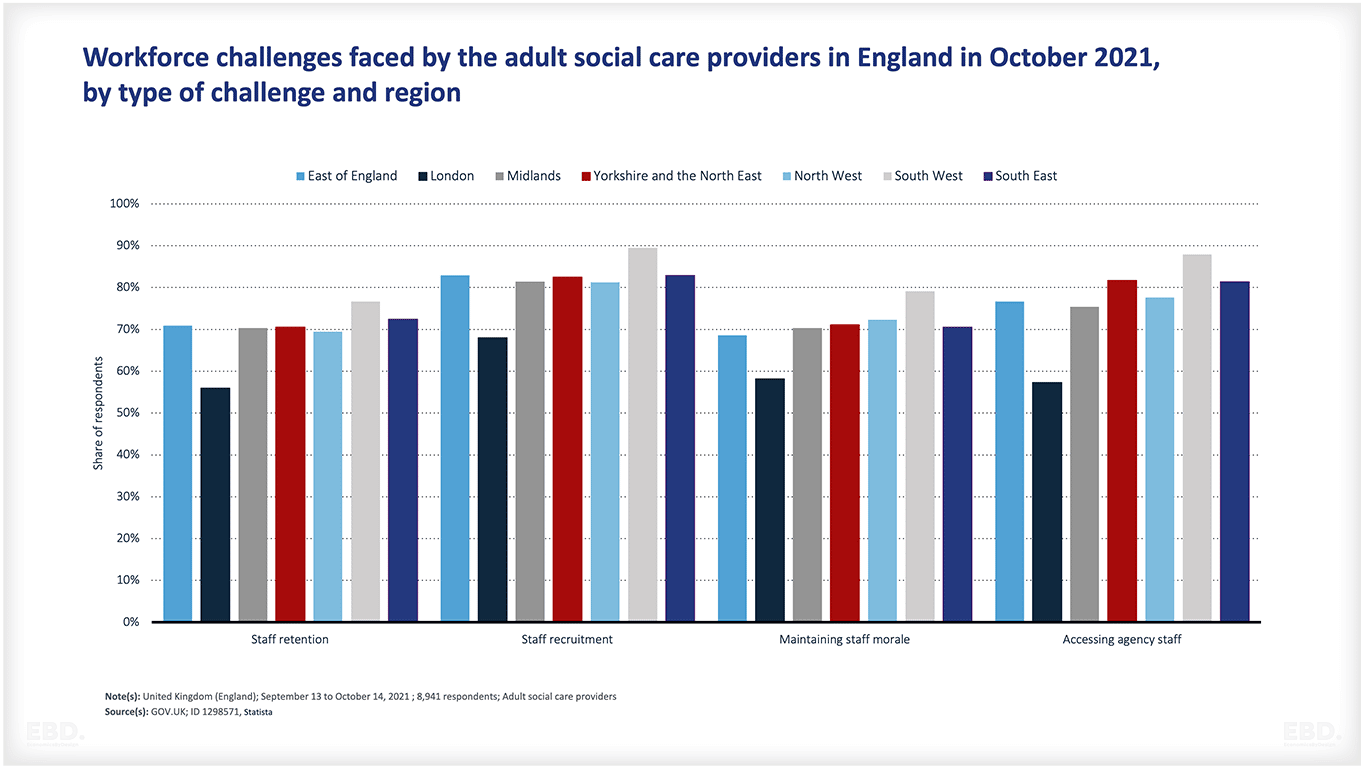

One of the key challenges associated with social care provision is shortages in the workforce. This poses difficulties for providers and can lead to a reduced quality of care or an inability to provide services when they are needed most. Common issues include high turnover of staff, inadequate training, lack of staff support and supervision, worker dissatisfaction with pay and scheduling and the changing nature of support work.

In Engand, Skills for Care recently reported that adult social care workforce vacancies have grown by 52% in the last year (2021-2022). Workforce challenges are faced throughout the country as can be seen from the chart below.

Unmet Need

Indicators of unmet need for social care services include waiting lists, large numbers of people in hospitals who no longer need medical or nursing care but are not able to be discharged safely due to lack of home care support or residential care, people living in residential care who could and would prefer to be at home were home care support available, and people who are over-reliant on fragile informal care support.

A relatively recent survey by Ipsos Mori in 2017 found that over half of older people with care needs in the UK had unmet need for support regardless of age, income / wealth and other socio-economic indicators. The study found that unmet need is frequently hidden and often results in poor social contact, loneliness and isolation which exacerbates health problems, frailty and overall dependency.

Finance and Incentives

Unmet need and workforce shortages are exacerbated by fragile funding schemes that are vulnerable to budget cuts compared to other areas of public spending. Some countries have separate arrangement for funding social care provided at home, and residential care. This risks perverse incentives with payers pushing responsibility across to other schemes through cost-shifting, lack of co-ordination, and inefficiency. This also impacts quality of service. In many countries service standards are ill defined and this results in quality skimping as finance tightens.

Self-direction

Self-direction is a growing trend with service users being given more freedom/flexibility over the design and delivery of their care package. In Germany, service users are given the choice of receiving care in cash or “in kind” with a significant majority choosing to take the cash even through it is of lower value. They are free to use the cash to pay for whatever support they need.

France Italy and Spain also have systems of cash benefits for individuals to use to purchase support from formal and/or informal carers. There is considerable flexibility particularly in Spain.

England has a national entitlement to cash benefits to help with the additional costs of long-term care which are available for individuals and carers. These cash benefits are taken into account as part of the means-test for access to state funded home support services provided by local authorities. In England, some local authorities are trialling Individual Service Funds which allow the user flexibility on the use of their entitlement.

Scotland has enshrined self-direction in and around 70% of people receiving social care services/ support are involved in choosing and controlling their support through self-directed options.

Australia has a single point of access to the system which is on-line and provides a co-ordinated navigation tool for individuals who need support. “My Aged Care”. They are also trialling System Navigators as their system is relatively complex.

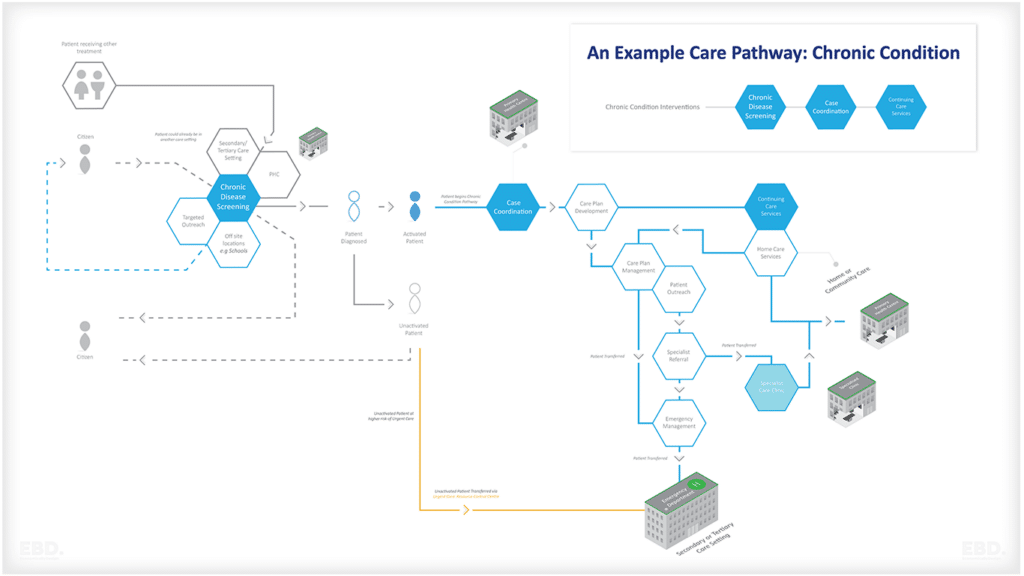

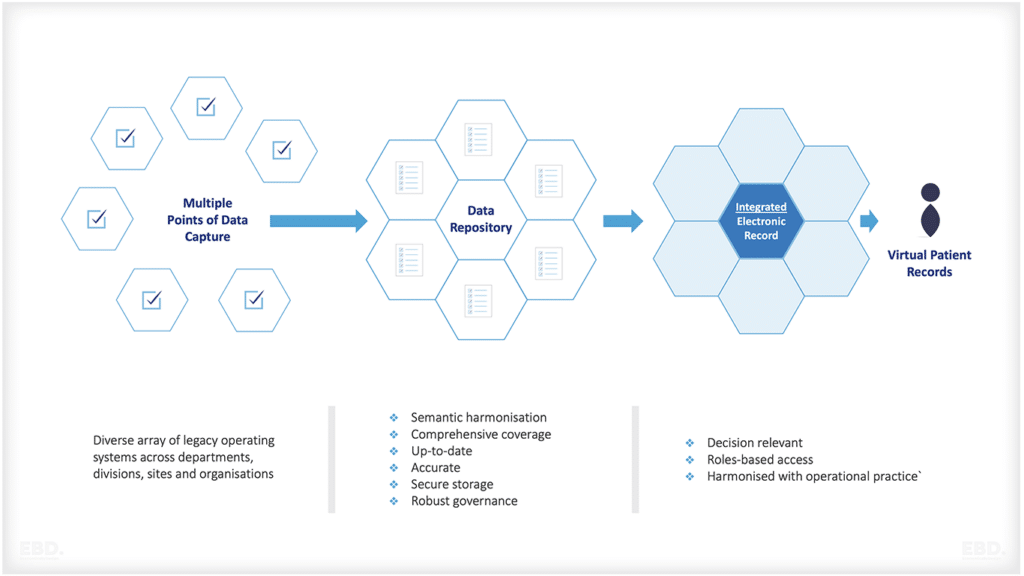

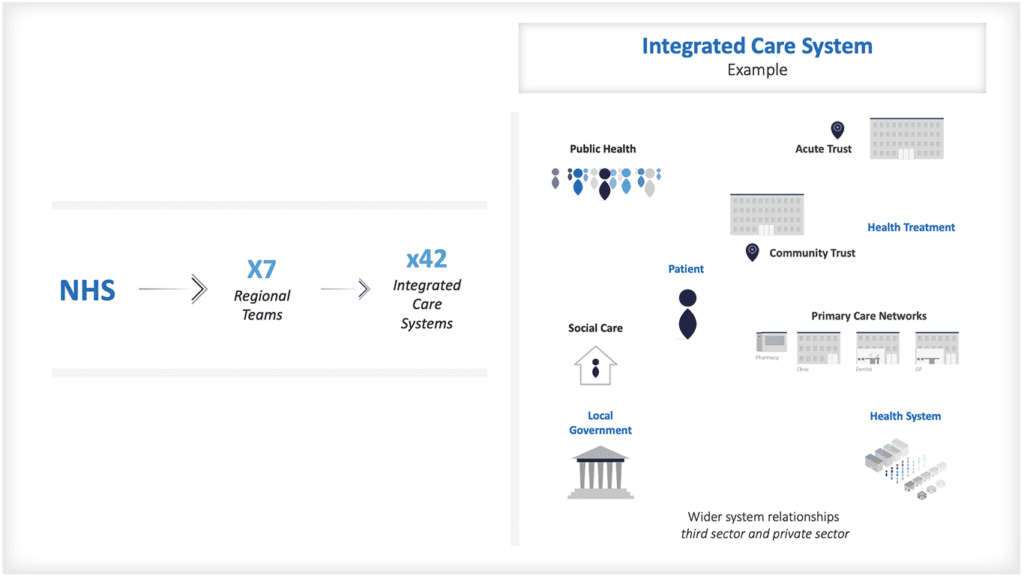

Poor integration between health and social care

Systems of care are being developed in many countries where health and social care work together to provide a more holistic approach to assessment, care planning, delivery and monitoring. However, there is frequently a lack of integration between health and social care pathways with different systems used for each. This results in duplication of effort, confusion for service users. Integration of health and social care is a key feature of the development of Integrated Care Systems.

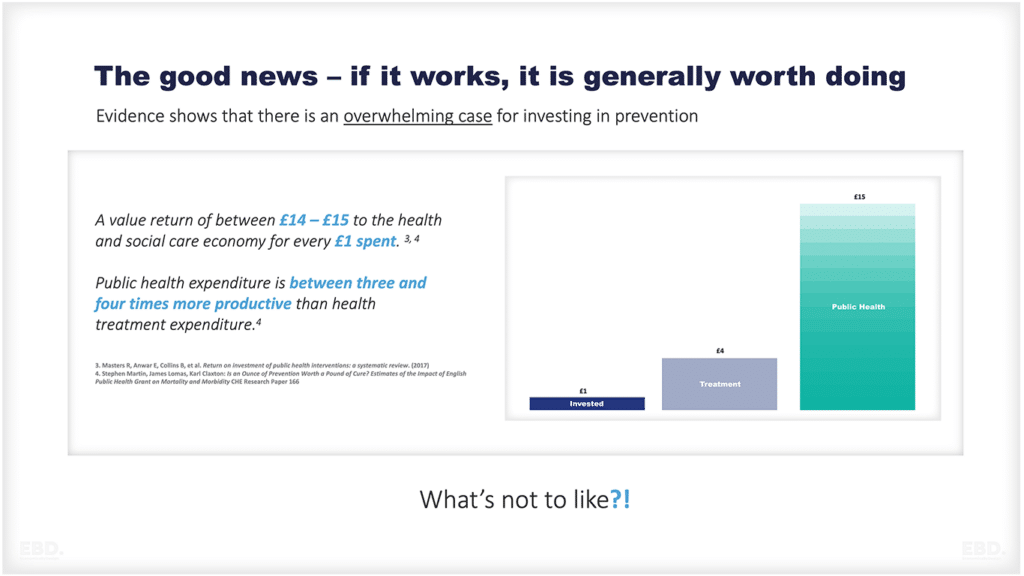

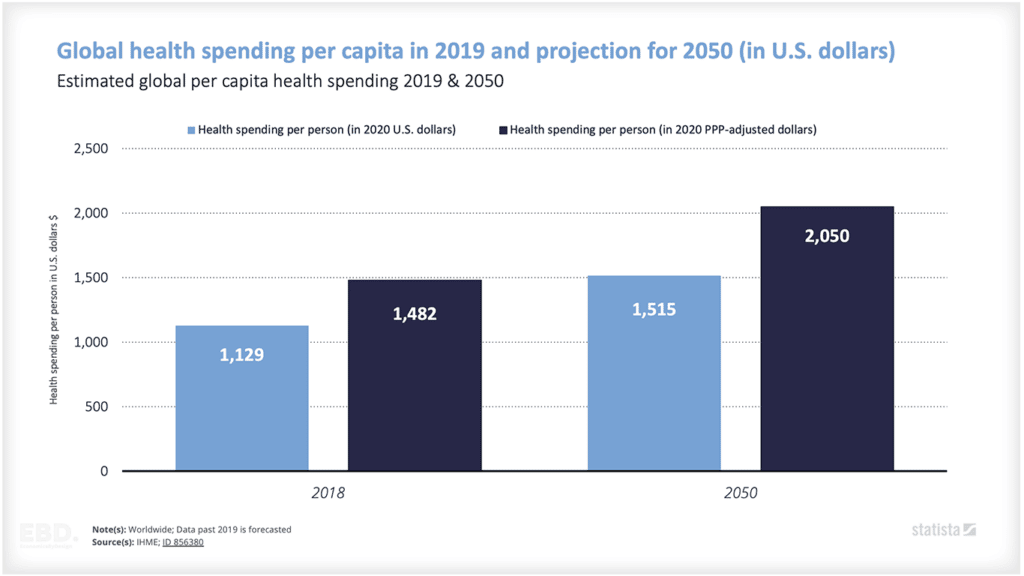

Economics of Social Care

Skills for Care estimate that adult social care contributes at least £50.3bn to the English economy. Around 50% of this was gross value added from the sector alone, with the remainder being the wider impact (the multiplier effect). The same report estimated that it accounted for 5% of the national workforce. In addition to these economic effects, the wellbeing effect is valued at an additional £9.2bn – £23.3bn. The report claims that investment of an additional £6.1bn is needed in the sector and that this would deliver a return on investment of 175% for the taxpayer. Similar studies have been undertaken for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Informal care makes a significant contribution, albeit unrecognised. A recent review suggests that across Europe, there are 76 million non-professional caregivers (around 12.5% of the population) providing Euros 576 bn of time (3.63% benchmarked against the size of Europe’s economy).

Sadly there is still very limited global research on the economic value of social care. However, it is clear that it provides a very important role in promoting wellbeing and preventing ill health and should be an integral part of any health and care system.

References:

- Curry, N. et al “What can England Learn from the long-term care system in Germany” Nuffield Trust, September 2019

- Alders, P. “The 2015 long-term care reform in the Netherlands: Getting the financial incentives right? March 2018

- Kelders, Y. et al “ESPN Thematic Report on Challenges in Long-Term Care: Netherlands, 2018.

- Iwagami, M et al. “The Long-Term Care Insurance System in Japan: Past, Present, and Future”, DOI: 10.31662/jmaj.2018-0015.

- Centre for Policy on Ageing “Foresight Future of an Ageing Population – International Case Studies”, 2016

- Duner, A. et al “Autonomy, Choice and Control for Older Users of Home Care Services: Current Developments in Swedish Eldercare” October 2018

- Szebehely, M. “Home care for older people in Sweden: A universal model in transition” December 2011

- Peterson, E. “Eldercare in Sweden: an overview” October 2017.

- Bottery, S et al “Home Care in England: Views from Commissioners and Providers” the Kings Fund, December 2018.

- Ipsos Mori “Unmet Need for Care Final Report” July 2017

- EC “Spain” Health Care and Long-Term Care Systems” An excerpt from the Joint Report on Health Care and Long-Term Care Systems & Fiscal Sustainability, published in October 2016 as Institutional Paper 37 Volume 2 – Country Documents

- EC, France: Health Care and Long-Term Care Systems” An excerpt from the Joint Report on Health Care and Long-Term Care Systems & Fiscal Sustainability, published in October 2016 as Institutional Paper 37 Volume 2 – Country Documents

- Matteo, J. et al “ESPN Thematic Report on Challenges in Long-Term Care: Italy 2018.

- Bihan, B. “ESPN Thematic Report on Challenges in Long-Term Care: France”, 2018.

- Tediosi, F. et al, “Long Term Care in Italy” June 2010

- Ilinca, S et al. “From care in homes to care at home: European experiences with (de)institutionalisation in long-term care.” 2015

- Skills for Care The value of adult social care in England: Why it has never been more important to understand the economic benefits of adult social care to individuals and society October 2021

- Joan Costa-Font and Nilesh Raut (LSE) “Global Report on Long-Term Care Financing” Report for the World Health Organisation. 2022.

- Peña-Longobardo LM, Oliva-Moreno J. The Economic Value of Non-professional Care: A Europe-Wide Analysis. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2021 Oct 30;11(10):2272–86. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2021.149. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34814681; PMCID: PMC9808255.