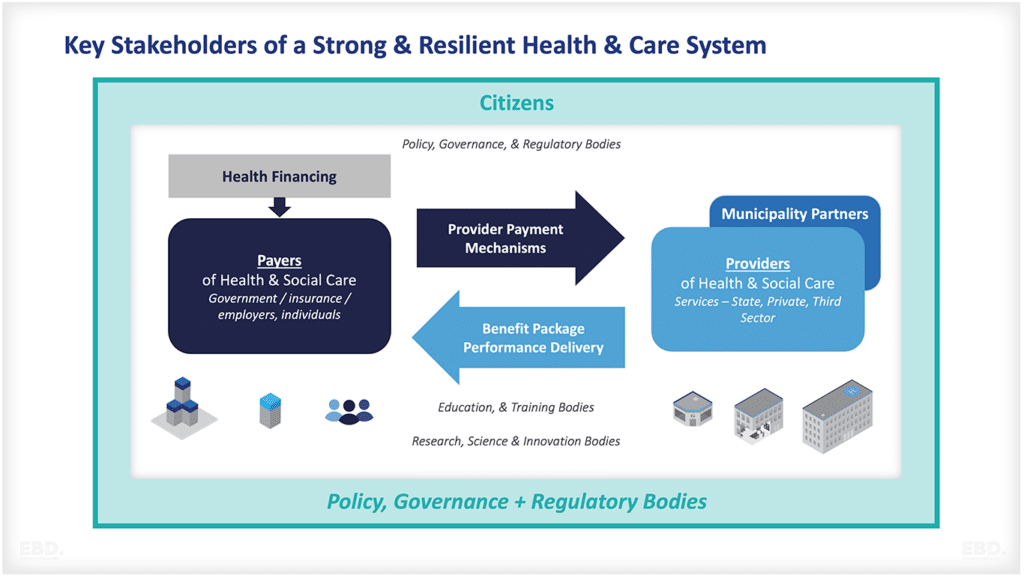

Health Financing

Health financing is a critical enabler of Universal Health Coverage (UHC). It ensures that people can access the universal coverage for health services they need without suffering financial hardship.

There are many different ways to flow funds through the health care system, but all systems have four basic elements:

Financing & Revenue Sources

This is when funds are gathered from people to pay for health care needs. This can be done at scale through government contributions, taxes, social insurance contributions, private insurance contributions, or philanthropic contributions. It also includes out-of-pocket payments by individuals paying directly for treatment when it is needed.

Risk Pooling

Funds gathered at scale can be pooled together in a way that allows them to be used more efficiently and effectively. This means that the risks of needing healthcare are shared among a larger group of people, which helps to keep costs down. Pooling can be done through a single fund for a whole health system, regional funds for sub-national systems, or multiple funds for specific population groups.

Strategic Purchasing

Pooled funds are used to purchase health care services for a group. This can be done directly by the government or through private insurers. It includes making contracts with providers, setting prices, and ensuring that quality standards are met.

Provider Payment Models

Providers (such as hospitals and doctors) need to be paid for the health care services they provide. This can be done through a variety of models, capitation, block funding, line-item funding, fee-for-service, case-based payments, or a mix of some or all. It can include incentives to improve performance or conditional on achieving pre-agreed outcomes.

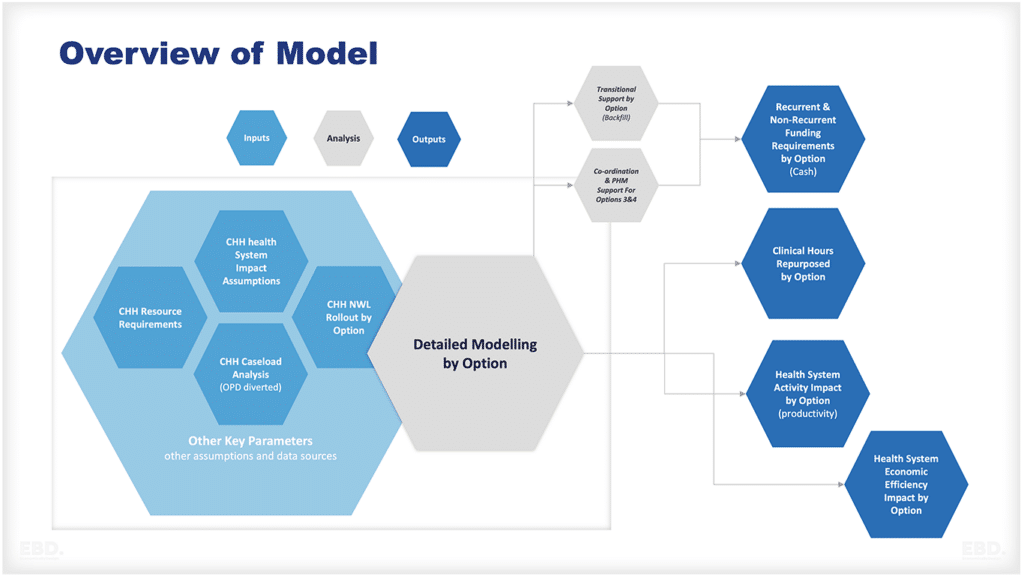

The focus of this economics lens is on the Provider Payment Models.

What is a Provider Payment Model?

A provider payment model is how money is transferred from a payer of healthcare to a provider of healthcare as fair and sustainable compensation for the costs faced by the provider for the delivery of population health programs, patient care and patient treatments.

Provider payment models can be used to achieve a number of objectives including:

- Improving access to care

- Reducing inequalities in health outcomes

- Supporting the delivery of evidence-based care

- Encouraging the use of effective and efficient care

- Improving the quality of care

- Reducing unnecessary variation in care

- Encouraging preventive care and health promotion

- Supporting the delivery of coordinated care

- Improving population health outcomes

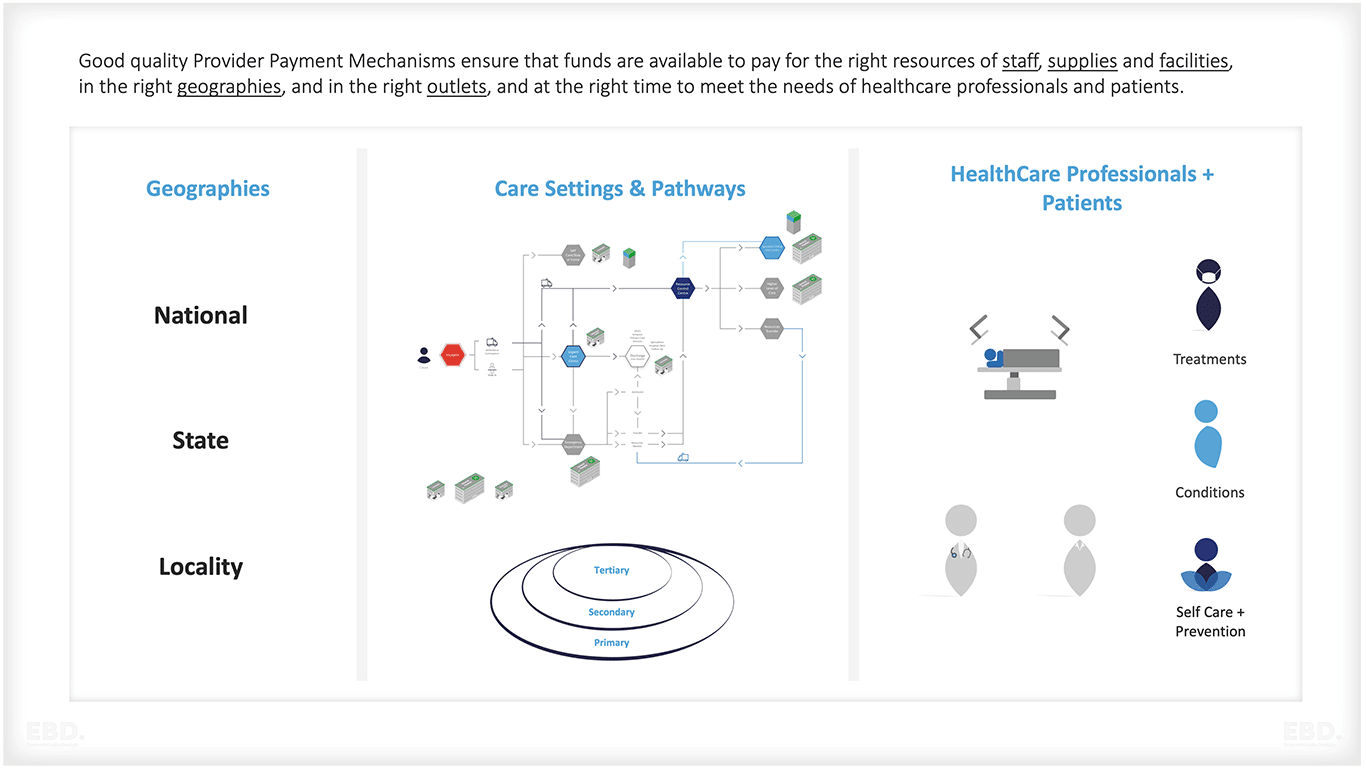

Good quality provider payment mechanisms ensure that the funds flow from their source to their destination quickly efficiently and fairly and enable providers to meet their costs and provide safe and effective services without delay or interruption.

What are the Different Types of Provider Payment Models?

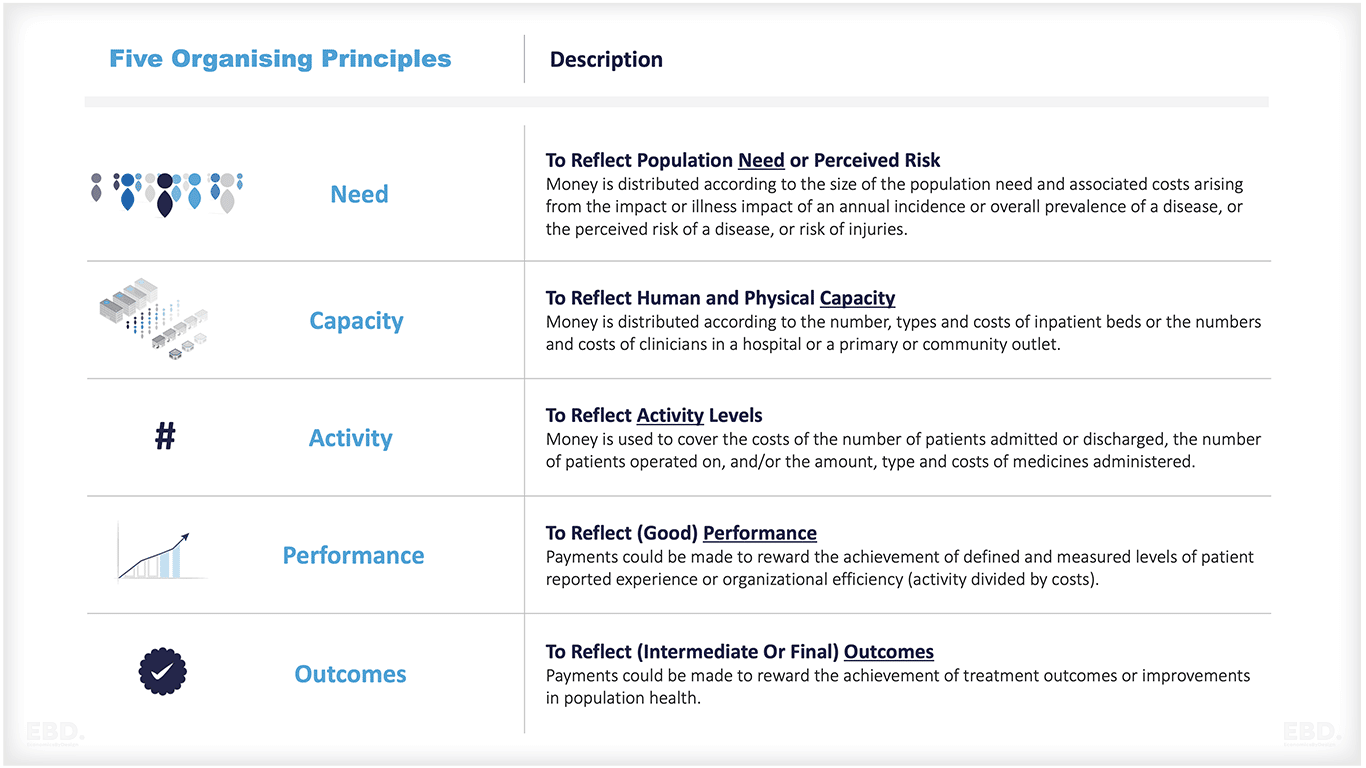

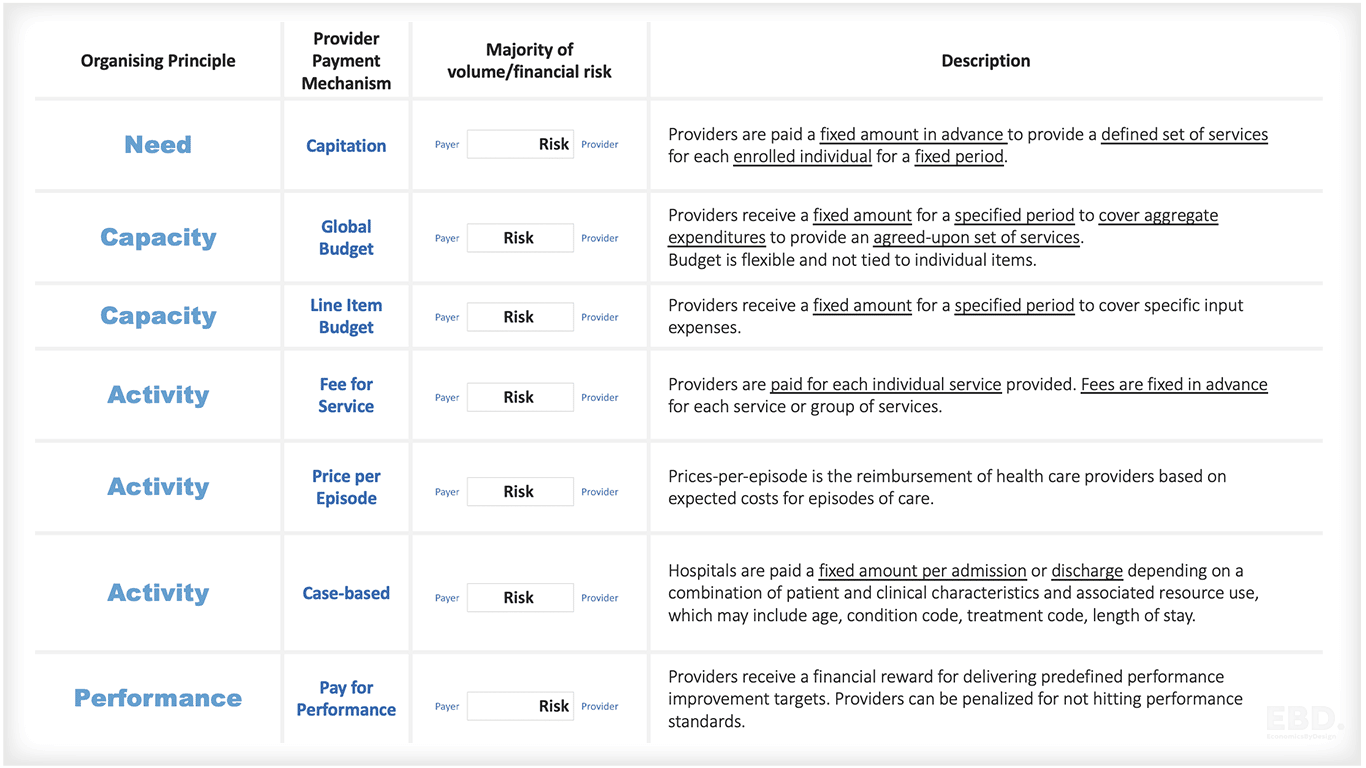

There are five key organising principles for provider payment models:

- Need

- Capacity

- Activity

- Performance

- Outcomes

Need

Here payment models reflect the costs of meeting the health needs of a predefined population. Using this principle money is distributed according to the size of the population, adjusted for relative need and associated costs.

These models are used to direct money to where it is most needed, equitably. Needs-based provider payment models are generally paid in advance, with potentially a retrospective adjustment if information comes to light which changes what the allocation would have been. The risk is generally held by the provider who has to manage all their resources within an envelope of funding that they’ve been allocated.

A good example of this type of provider payment model is capitation. Capitation is a type of provider payment where providers are paid a fixed amount per patient on their panel, irrespective of the number or type of services provided. The idea behind this model is that it gives providers an incentive to prevent ill health and promote wellness, as they will be paid the same amount regardless of whether the patients they are caring for are healthy or not.

Capitation can also be used as a way to budget for health services, as it gives providers a set amount of money to work with each year. This can help to manage costs and ensure that providers are not overspending.

However, capitation can also lead to underfunding, as providers may not be able to meet the needs of their patients if the amount they are paid per patient is not enough to cover the costs of care.

Payment models in many countries have an element of capitation including Finland, Sweden, Norway and England. The Centres for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in the USA use capitated models to contract with a state and a plan to deliver comprehensive coordinated care.

Capacity

This principle is designed to reflect the need for human and physical capacity. Here money is distributed according to the number, types and costs of physical facilities such as inpatient beds or theatres or the numbers and costs of clinicians, and other staff, in a hospital or a primary or community facility.

Capacity-based provider payment models are useful when payers are looking to create or protect the capacity of the system to deliver a range of services. This approach can provide financial security to new and existing providers and it is appropriate to use this where capacity is developing and is potentially fragile and to provide security to those providers by paying for their capacity directly.

Payments are generally paid on a prospective basis with a balance of risk between the provider and the payer in terms of the sufficiency of funds to secure the required capacity.

One of the biggest challenges with paying for capacity is increasing output and mobilizing improvement. Simply paying for the staff or physical infrastructure can result in under-use and inefficiency. It is also difficult to stimulate improvement in performance and outcomes.

Examples of capacity-based payment models include:

Global Budget

In a global budget, the provider is given a set amount of money to cover all of their costs for a period of time. This can be an annual budget or it can be for a shorter period such as 6 months. The provider is then free to use this money as they see fit.

Block Grant

A block grant is similar to a global budget but it is usually for a specific purpose such as to cover the costs of capital investment or to pay for a specific type of service.

Line Item Budget

A line item budget is where the provider is given a set amount of money for each item on their budget. For example, they may be given a set amount of money for staff costs, for rent, for electricity, etc. This type of budget can be inflexible and it can be difficult to make changes if the needs of the provider change.

Governments in Low and Middle-Income Countries often pay or fund their providers using these types of payment models.

Activity

The third organising principle is activity. This principle is designed to encourage the delivery of required activity levels. Here money is used to cover the costs of the number of patients admitted or discharged from the hospital, the number of patients operated on, or the amount and types of costs of medicines administered and treatments delivered.

Provider payment mechanisms based on the organising principle of activity are useful when you are trying to incentivize an increase in healthcare outputs. This is useful when capacity is quite secure but it’s underperforming, maybe it’s not being used very effectively, and you want to encourage greater volumes of care to be processed through the health system.

One of the challenges of using provider payment mechanisms that focus solely on activity is managing financial constraints. Paying for an activity can risk overtreatment and unnecessary intervention. It also risks overspending which means money will run out before the end of the year if activity targets are exceeded.

Examples of activity-based payment models include:

Fee-for-service

Fee-for-service is where the provider is paid a set fee for each service that they deliver. For example, they may be paid a fee for each patient that they see, or for each operation that they perform.

Diagnosis-related groups

Diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) are where the provider is paid a set fee for each patient with a particular diagnosis. For example, they may be paid a higher fee for a cancer patient than for a patient with a cold.

Case-mix

Case mix is where the provider is paid a set fee for each type of case that they treat. For example, they may be paid a higher fee for an accident case than for a medical case.

Countries that use activity-based payment models include

- Australia

- Canada, France

- Germany

- Italy

- Spain

- United Kingdom

- United States.

Performance

The fourth organising principle is performance. This principle is designed to reflect the need to improve performance. Payments could be made to reward the achievement of defined and measured levels of patient-reported experience or organisational effectiveness or efficiency.

These are useful where you’re trying to change or improve practice or to achieve tactical objectives such as reductions in waiting times, or investment in information technology. It is appropriate to use this where the capacity itself is secure, but the system may not be performing as well as it can.

Performance-based payment models should be paid on time or near the time of achievement of the targets. The balance of risk is generally borne by the provider for failure to deliver against performance targets.

These types of payment models can create perverse incentives. These are incentives that encourage providers to take the wrong actions. Payment for performance can result in too much focus on a few measurable outputs at the expense of good patient care. General targets to reduce waiting lists for example can result in urgent cases waiting too long.

Outcomes

Here payments could be made to reward the achievement of treatment outcomes or improvements in population health.

Outcome-based payment models should only really be used when you want to empower the system to design and deliver transformation and change at the front line of care. They rely on the payer having confidence in the providers’ ability to deliver and innovate to improve population health and to deliver high-quality treatment and care outcomes.

These payment models are generally very retrospective, and the balance of risk is largely borne by the provider. Failure to achieve outcome measures will result in lower than expected funding levels. This in turn risks compromising the sustainability of small organizations. Paying for outcomes requires the provider to be sufficiently large to manage or pool the risks across a population where needs are not individually predictable. The provider also needs to be financially secure.

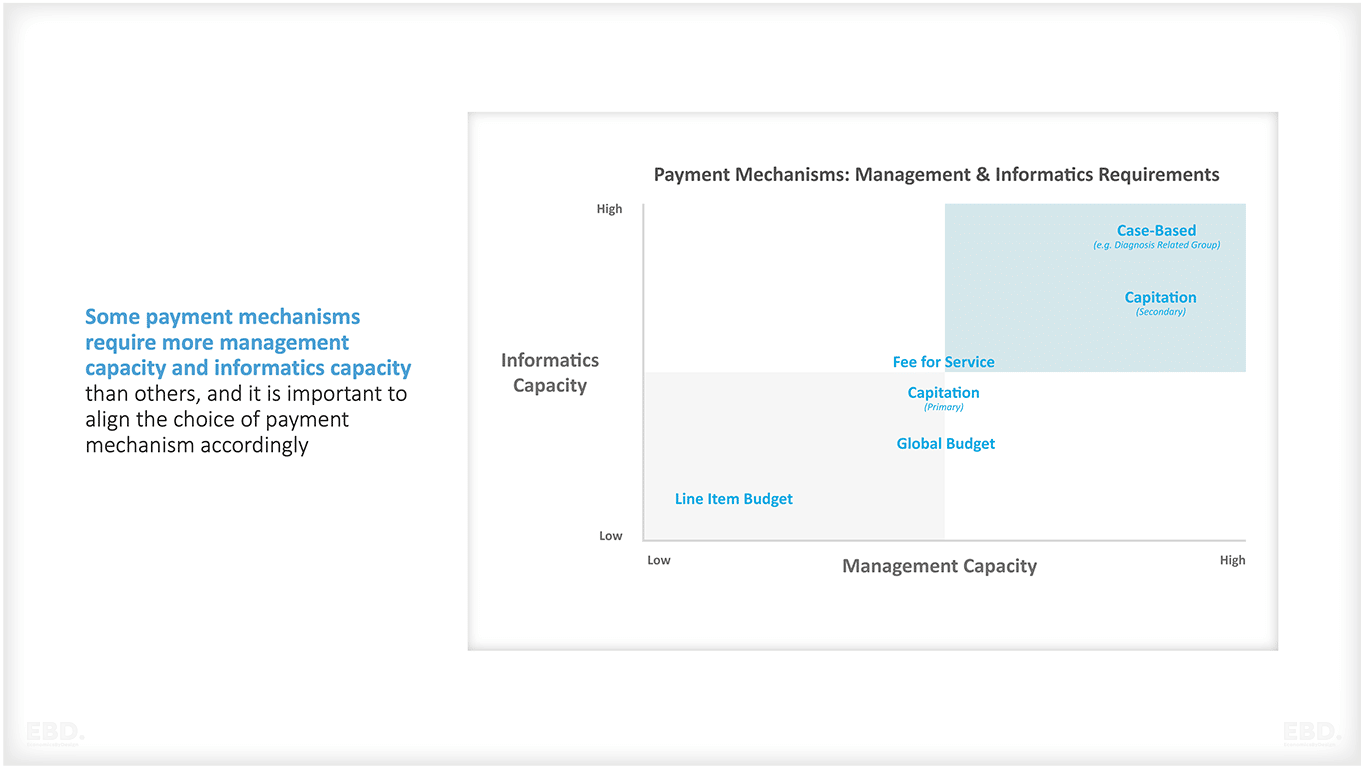

Blended Payment Model

Many payers use a mix or blend of these payment models depending on what they are being used for and the problem they are trying to solve. When payment models are blended care is needed to avoid systemic perverse incentives. For example, if capitation is used to pay primary care providers, whilst activity payments are used to pay secondary care providers, this creates an incentive for primary care providers to refer to secondary care effectively shifting the costs of care.

The secondary care providers will take the referrals as they will be paid according to their activity levels. In combination, these result in over utilisation of health services and increase the costs to payers.

Payment Model Incentives

The incentives that different provider payment models create need to be carefully considered as these can result in unintended consequences. The use of a single provider payment model risks creating perverse incentives that lead to sub-optimal care. Provider payment models should therefore be designed with the desired system-level outcomes in mind, and the potential perverse incentives each model creates should be mitigated.

For example, if the payer wants providers to focus on quality and safety then a payment model that rewards providers for meeting targets around these outcomes are likely to be effective. However, if the payer wants providers to focus on efficiency then a payment model that rewards them for meeting targets around cost reduction is likely to be more effective.

It is also worth noting that provider payment models are not the only mechanism that can be used to influence provider behaviour. Other mechanisms such as regulation and accreditation can also be used.

What is important is that any provider payment model is designed in a way that achieves the desired system-level outcomes whilst minimising perverse incentives.

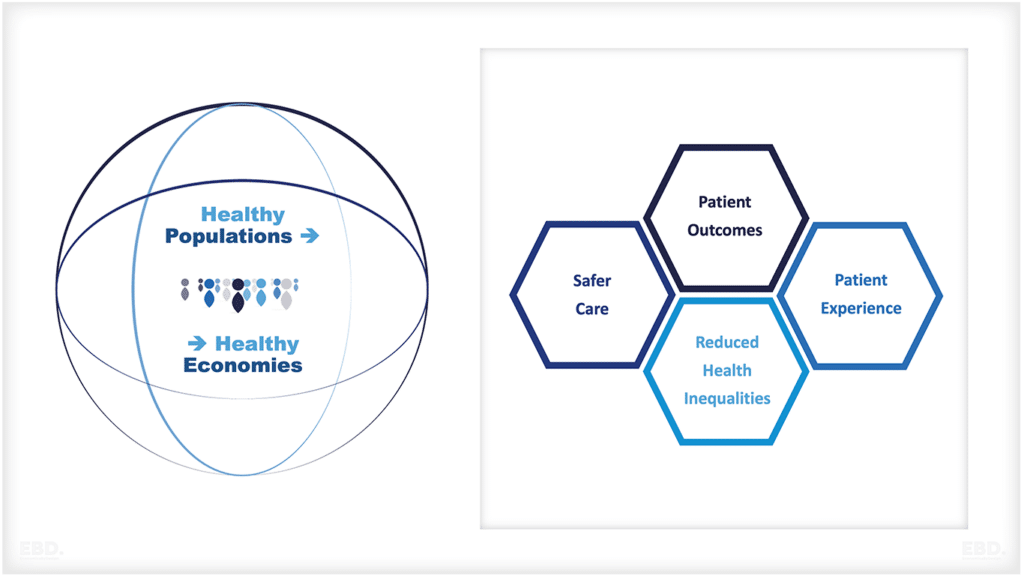

Value-Based Payment Models

Value-based payment models have been gaining in popularity in recent years as a way to improve the quality and efficiency of healthcare. These models are designed to pay providers based on the value they deliver rather than the volume of care they provide. The thinking behind these models is that paying for value will incentivise providers to focus on delivering high-quality, cost-effective care.

Value-based payment models are generally seen as being more effective at incentivising quality and efficiency than traditional provider payment models. This is because they create a direct link between provider performance and payment.

The main criticism of value-based payment models is that they can be complex to design and implement. This complexity can make it difficult to achieve the desired outcomes and so these models need to be carefully designed if they are to be successful.

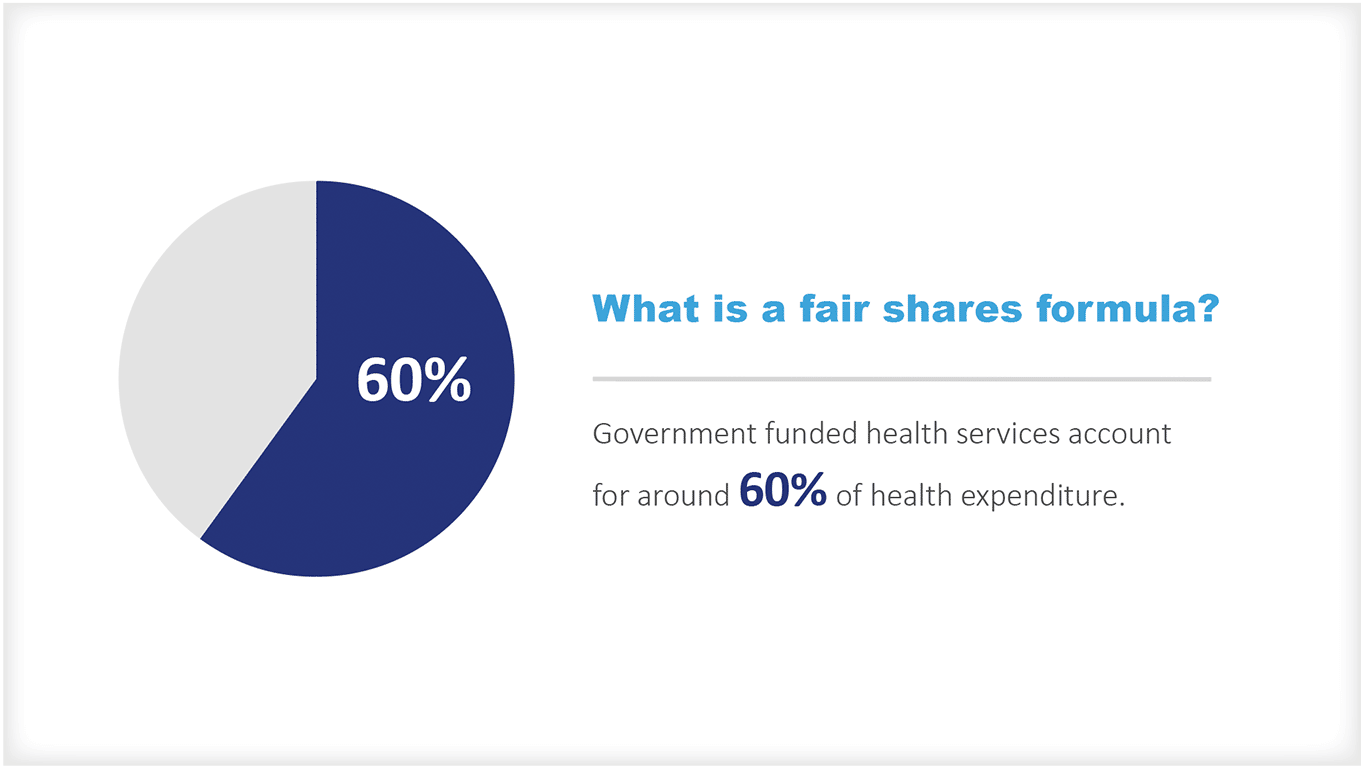

What is a Fair Shares Formula?

Resource allocation

Government funded health services account for around 60% of health expenditure [1]. One of the big challenges facing governments is how to share these resources across geographies, and populations to enable equity of access to services locally.

One of the earliest examples of a ‘fair shares” formula was the one used by the NHS in England to allocate resources to regional health authorities. Known initially as the Crossman Formula [2], the approach was developed by a working party established in 1975 known as the Resource Allocation Working Party (RAWP).

The RAWP formula, was used to set target funding allocations based on giving populations equal access to health services for those in equal need. The formula was relatively crude but represented a huge improvement on the historic funding which preceded it and showed huge unwarranted disparities in funding, especially favouring London.

In my early days at H.M. Treasury in the late 1980’s, I was part of the review of RAWP. This review resulted in the establishment of a more complex formula which has been successively improved on ever since.

As it improved, instead of being used to allocate funds to 14 regions it was developed to enable a capitation funding approach for over 200 local commissioning groups. The basic approach is still in use today despite several major overhauls [3].

Allocative Efficiency

Seen through an economic lens this is all about ‘allocative efficiency’, namely ensuring geographical alignment between the underlying need for health services and their supply [4].

What are the Important Design Principles?

There are several important designing principles which influence these formulas:

- The care setting (e.g., primary healthcare, hospital services, community health services, prevention etc.)

- The services being funded (e.g., maternity, mental health, general acute services)

- The determinants or factors which will influence the need for these services (e.g., size of population, demographics, socioeconomics, epidemiology etc.).

- The determinants of factors which influence the supply of these services (e.g., historical service provision, local operational policy (prevention vs treatment/response), inter-sectoral stakeholder relationships (few public services are provided in a vacuum), and alternative provision (such as the private sector).

- The influence supply has on the perceived demand for services (e.g., for those localities focusing operational policy on prevention, this may reduce caseloads which will be seen as evidence of lower demand – however underlying needs may not have altered at all).

- Unavoidable differences in costs (e.g., particularly due to local labour market conditions).

- The Government’s strategic policy objectives for these services and whether certain practices need to be incentivised or discouraged. A good example of this is the current NHS priority on reducing surgical waiting lists.

- The timeliness, frequency, and accuracy of data available to keep the formula up to date.

- The clarity and transparency of the formula and perceptions of “fair shares”.

- Locality level target allocations vs current allocations, distance from target.

- The stability of target allocations as data are updated from year to year.

- The policy covering pace-of change from current to target allocations.

That’s quite a lot to consider. It’s not surprising, therefore, that there is always a healthy methodological debate about what should be included and excluded, what data to use, and how to ensure that the formula is genuinely fair. It is no surprise either that there is an army of health economists who have dedicated their careers to this challenge.

Levelling across vs levelling up

One of the biggest challenges of a fair shares’ formula is the implication that you need to move money from one area (the losing area) to another (the gaining area). This is tricky from a political and a policy perspective.

It is tricky even if the area losing has relatively low need but has previously been well endowed with resources and the area gaining has relatively high need, but historically experienced low levels of resources. However, it is even more difficult if an area of high need is also a loser.

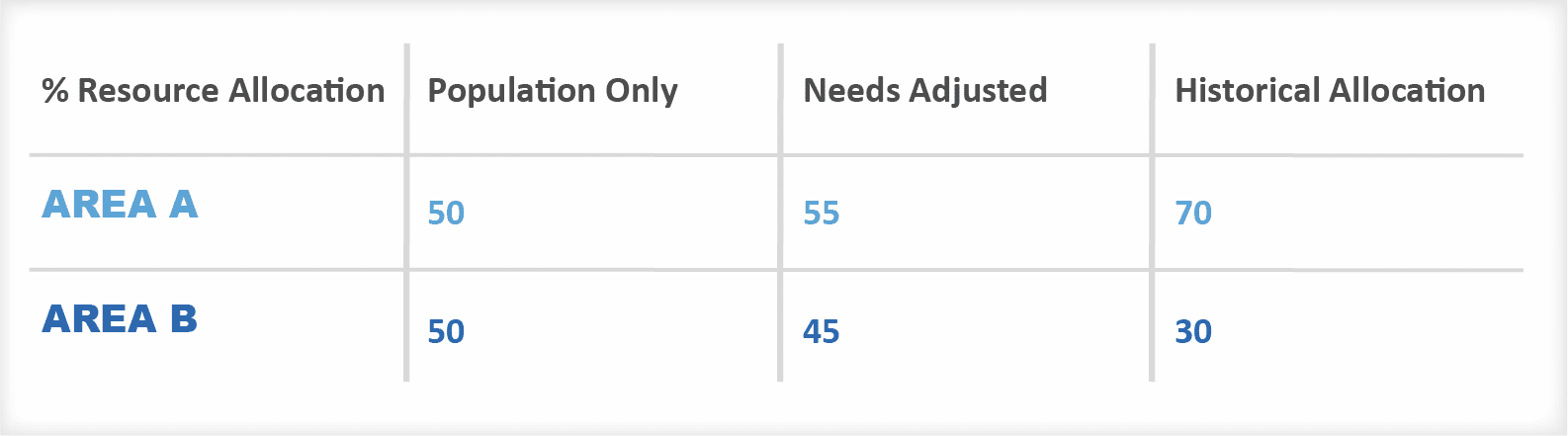

Think about Area A compared to Area B – the same size in terms of population. If we assume that Area A is 10% more needy than Area B, then allocating based on need would give Area A 55% of the funds available.

But what if Area A had historically received 70% of funding. Allocative efficiency suggests we should move money away from Area A and give it to Area B even though Area B is less needy.

Governments often adopt policies regarding ‘movement to target” or ‘pace of change” which try to address these challenges by using new funding, or budget increases to rebalance.

New money each year goes to “gaining areas” and “losing areas” have their current budgets protected. The problem with this “levelling up” is that it can literally take a generation to address historical inequities.

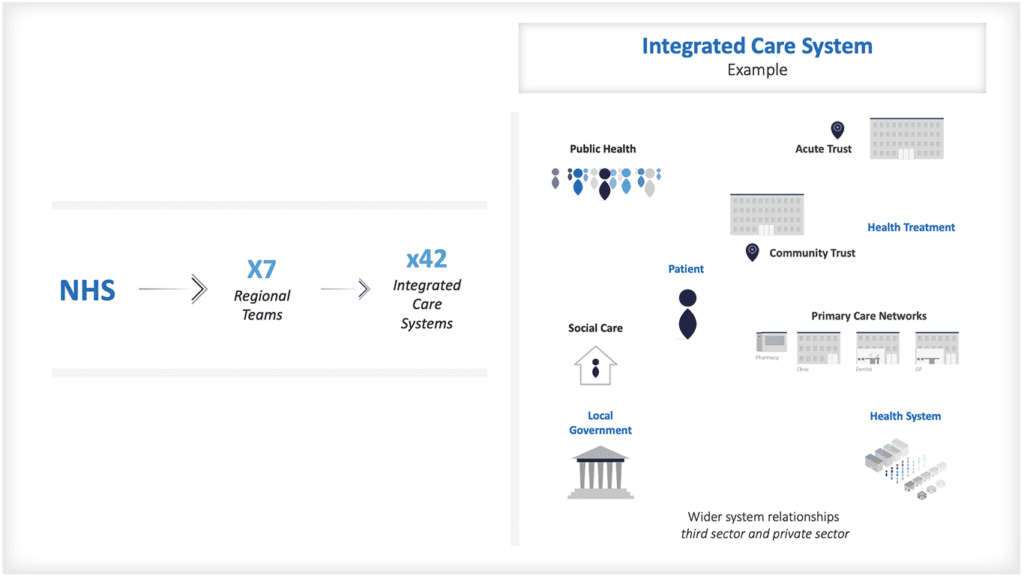

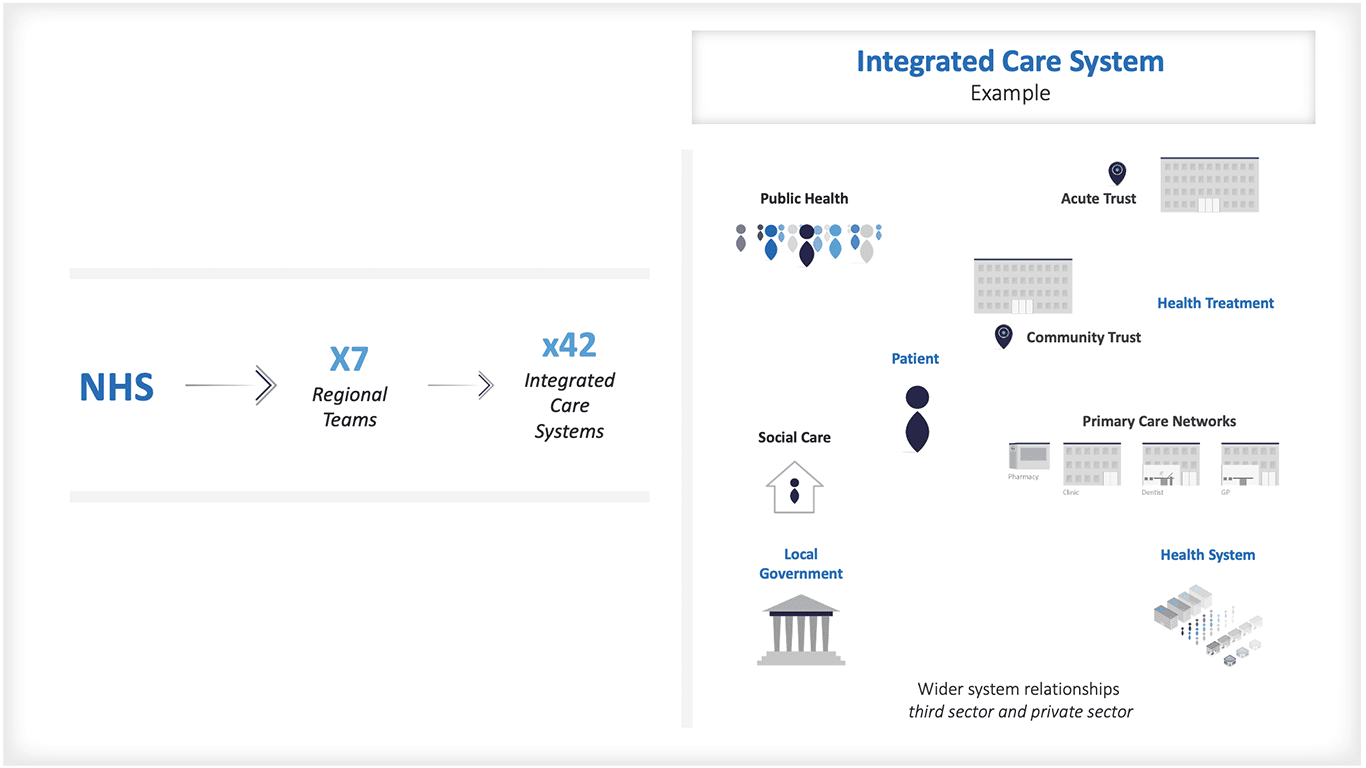

Integrated Care Systems

It will be interesting to see how things progress for the NHS in England as the new Integrated Care Systems are established. The formula will essentially be used to allocate resources to 42 health systems, leaving them much discretion in how to allocate funds to localities and neighbourhoods.

It is likely that Integrated Care Systems will have to balance strategic purchasing, capacity development, and targeted initiatives for improving population health and reducing health inequalities. Maybe the formula approach to fair shares funding will in future be limited to regional distributions?

[1] /the-economics-of-health-financing-how-much-is-enough/

[2] //www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/improving-the-allocation-of-health-resources-in-england-kingsfund-apr13.pdf

[3] //www.england.nhs.uk/publication/infographics-fair-shares-a-guide-to-nhs-allocations/