Personal Wellbeing at Work

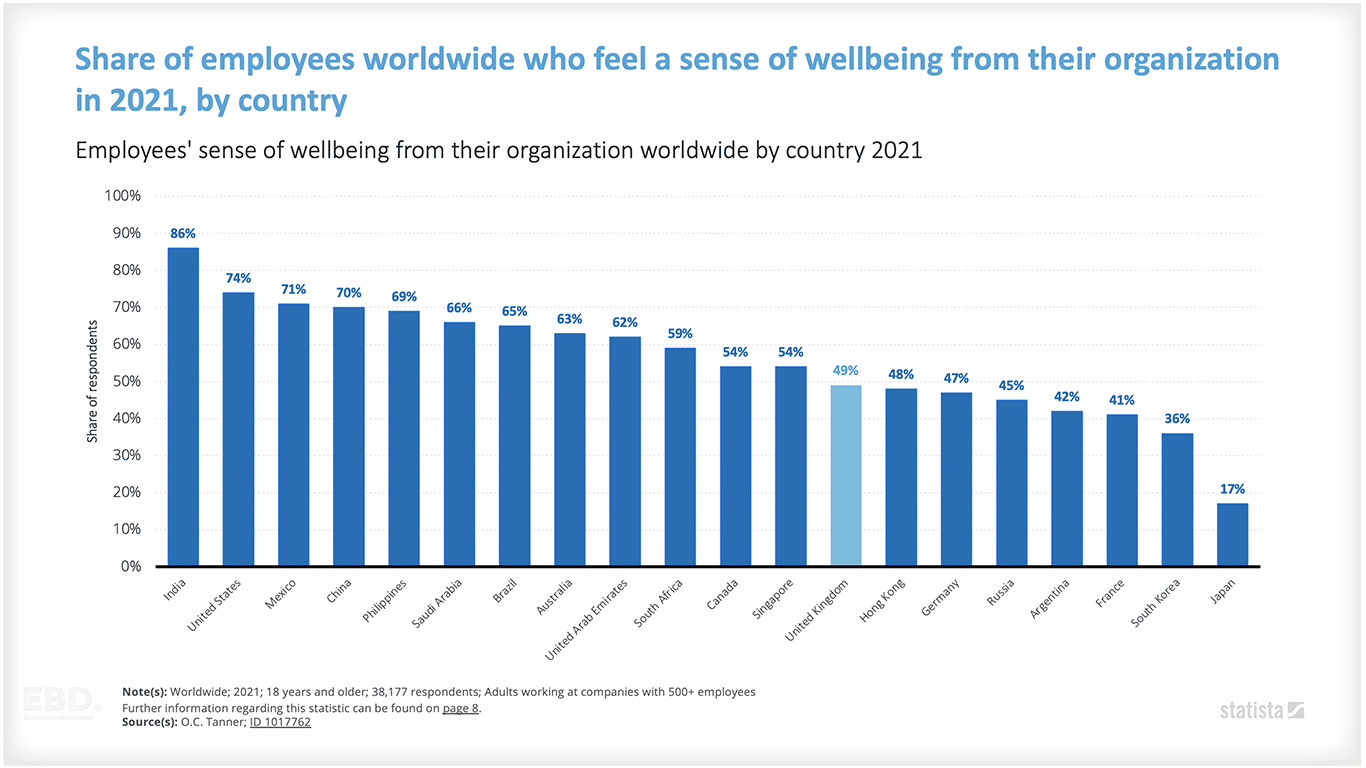

According to a study conducted by O.C. Tanner in the 2022 Global Culture Report, only 49% of employees in the UK feel a sense of personal wellbeing from their organisation. This compares with a staggering 86% in India and only 17% in Japan.

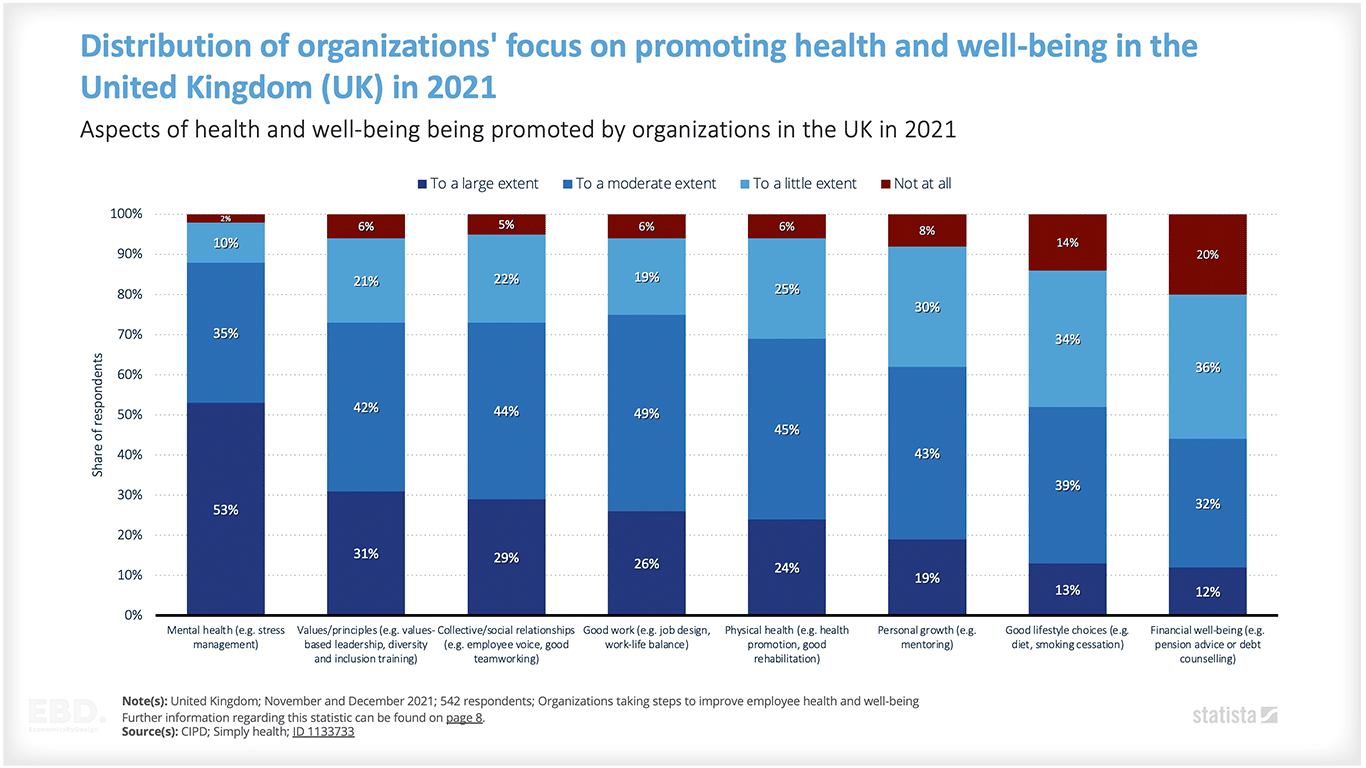

The Health and Wellbeing at Work Report 2022 from CIPD and Simply Health found that, across the UK, where organisations are focusing “to a large extent” on promoting wellbeing, their main focus is on mental health (53%). This is probably just as well given the high cost to employers of presenteeism, absenteeism and turnover (Economic Value Healthy Workforce).

Interestingly, much less attention is paid by employers to their employees lifestyle choices (13%) and to their financial wellbeing (12%). Given the impact of poor lifestyle on life expectancy, and the current cost of living crisis, maybe employers will invest more in these areas in the future.

Dimensions of life that matter to people

The ONS also measure ten dimensions of life that matter to people.

Personal Wellbeing & Government Policy

What does the government think about personal wellbeing and the potential for public policy decisions to improve personal wellbeing? Does personal wellbeing have any value? If so, how can that value be estimated in monetary terms?

All of these questions seem to have been answered by the new supplementary guidance to the H.M. Treasury Green Book. Authored by the Social Impact Task Force, the new Wellbeing Guidance for Appraisal: Supplementary Green Book Guidance, July 2021 covers all these questions.

The guidance introduces a new personal wellbeing metric in Green Book currency. Health economists have been using the Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY) for many years to measure health outcomes. Recently the H.M. Treasury has placed a monetary value of one year of life in perfect health at £70,000. Now we have the Wellbeing-adjusted Life Year (WELLBY).

Developed by Paul Frijters and Christian Krekel, One WELLBY is “a one-point change in life-satisfaction for one year”. According to the H.M. Treasury each WELLBY has a monetary value of £13,000 (between £10,000 and £16,000)!

Interestingly, the WELLBY methodology is not just a UK phenomenon. It is also adopted in New Zealand. The World Wellbeing Panel predicts it will soon become standard use across OECD countries.

What is personal wellbeing?

In essence, personal wellbeing is about how you feel. As citizen representatives and custodians of tax revenues, governments should care about how people feel. In recent years, there has been increasing pressure from economists to measure and monetise this in the same way as is done for the traditional measures of economic health, namely Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

How do we measure personal wellbeing?

Known as the ONS4, the Office for National Statistics uses four questions about personal wellbeing in their annual population survey:

- “Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?”

- “Overall, to what extent do you feel the things you do in your life are worthwhile?”

- “Overall, how happy did you feel yesterday?”

- “Overall, how anxious did you feel yesterday?”

Respondents answer on a scale of 0 = not at all, to 10 = completely. The ONS has been collecting this data for over a decade. In Q2 2011, the mean average score of life satisfaction was 7.37.

It increased to 7.7 by 2019, but then dropped back during the COVID-19 pandemic reaching a low of 7.28 in Q1 2021. Back on the rise to 7.6 Q3 2021, who knows where it will land as the cost of living crisis starts to bite at the end of 2022.

How people feel can reflect personal experiences across all of these different dimensions. Generally speaking, the more of everything you have the higher your life satisfaction. If one measure is low, any negative impact on life satisfaction may be offset by another measure being high. Economists and social impact researchers have been doing lots of interesting research on these relationships.

The Value of Personal Wellbeing

This is where it gets really tricky. All other things being equal, an improvement in life satisfaction should, in theory, provide positive value. But that depends on where you start from.

If life satisfaction is really poor (0-3), a one point improvement might be significantly more valuable to an individual, than if life satisfaction is already good (7-9). The benefit might also be transitory. Perhaps more importantly, measures of personal wellbeing are self-reported. This is why wellbeing is often referred to as “Subjective Wellbeing”.

The Monetary Value of Personal Wellbeing

The economists who worked on the guidance have calculated an average value of £13000. This is basically the mid-point between a lower value of £10,000 and a higher value of £16,000.

- The lower value (£10,000) is based on research which suggests that one QALY is associated with a 7 point change in life satisfaction. So, if one QALY is worth £70,000 then a 1 point change in life satisfaction must be worth £10,000.

- The higher value (£16000) has been calculated on the basis of estimates of willingness to pay for improvements in life satisfaction.

Do We Need to Place a Monetary Value on Personal Wellbeing?

Often economists are asked to help demonstrate return on investment. But often in welfare economics, and even in the narrower field of health economics, there are “intangible”, subjective benefits which make a difference. These benefits make a difference when choosing between different options and when choosing to invest at all.

Having a measure such as the WELLBY and having an established unit valuation, will allow economists to include these measures as part of benefit to cost ratio or return on investment calculations.

Consider an investment in a digital health product that reduces anxiety and stress for health professionals – maybe it is a scheduling system or something which gives them more control over the management of conflicting clinical priorities. The benefits of this are truly hard to value.

We can look at the perspective of the employer, for example, by measuring the potential longer term impact on presenteeism, absenteeism and staff turnover. But this is hard to do, particularly when trying to establish causality. Without considering the value of the impact on personal wellbeing, it may be hard to justify the investment.

Even more complex is a situation where a new technology saves money but has a genuinely negative impact on personal wellbeing (for example something as simple as being noisy). At the moment, these are reflected in narratives describing the potential negative impact, but which are at risk of being largely ignored if the operational financial efficiencies are positive.

So having a standard measure and value should really help improve the targeting of tax funded public sector investment and resources.

Some think that measuring and valuing personal wellbeing is not helpful. The idea that ratings of life satisfaction on a scale of 0-10 are reliable, comparable, scalable and supported by psychology is itself very controversial.

Professor Anna Alexandrova, from the Bennett Institute for Public Policy, Cambridge, recognises that economic measures such as GDP and WELLBYs tell us something about societal wellbeing, but that they should not be substitutes for making political decisions. She argues that the idea of a “master number” reflects a more fundamental problem with the way we look at the world. The “rational individual” in neoclassical economics at its very worse.

Way back in the midst of time, QALYs were received with equal scepticism. Now, however, QALYs are an internationally accepted utility metric for health outcomes. The ‘science’ of measuring QALY values has grown in breadth, depth and sophistication over the last fifty years. Let the sceptics not dismiss the WELLBY too soon. It may well have its place as an important tool in the economists box of tricks.