Essential Health Benefits: An Introduction

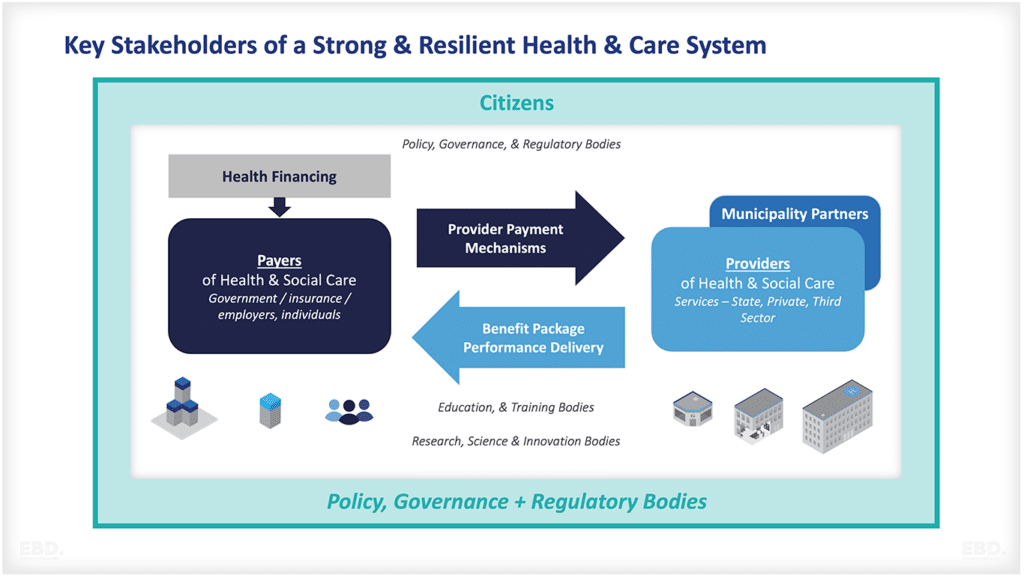

Governments and health insurance providers use pooled funds to purchase essential health benefits for their citizens or insured populations. Health benefit packages are the collection of health prevention, treatment, care, and rehabilitation services which are provided to these populations. They vary in scope from scheme to scheme and country to country. Definitions of what is included or excluded can be either very loose or very detailed.

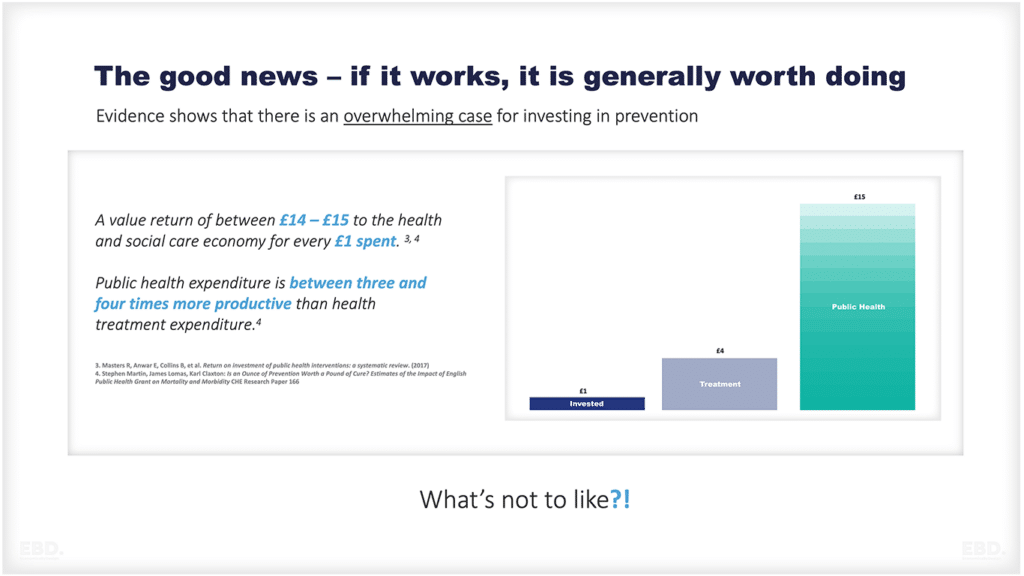

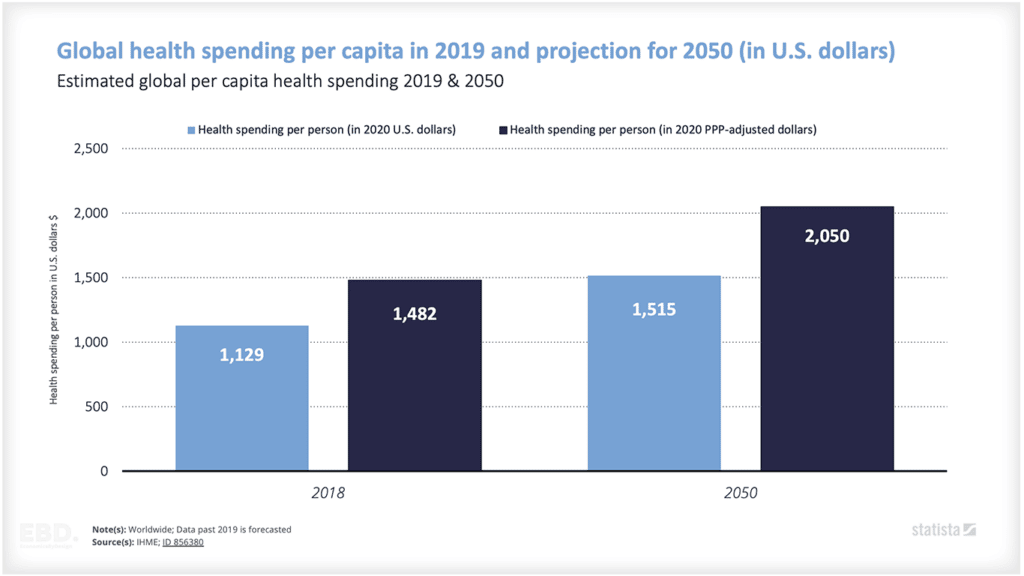

The demand and need for health are continuously growing but resources for health are limited. Therefore, ensuring the best value for every dollar spent on health has been placed high on governments’ agenda.

Economic considerations are increasingly prominent in the planning, management, and evaluation of health systems (Chisholm & Evans, 2007;Turner et al., 2021). The use of health economic analyses can help assess value for money and support decision makers in the allocation of scarce resources.

The fundamental problem however is that there is no universally agreed scope for cost effectiveness analysis. In some studies, cost effectiveness will be restricted to an examination of the costs and benefits for the patient and for the health system. In other studies, cost effectiveness analysis will also include the impact on wider society.

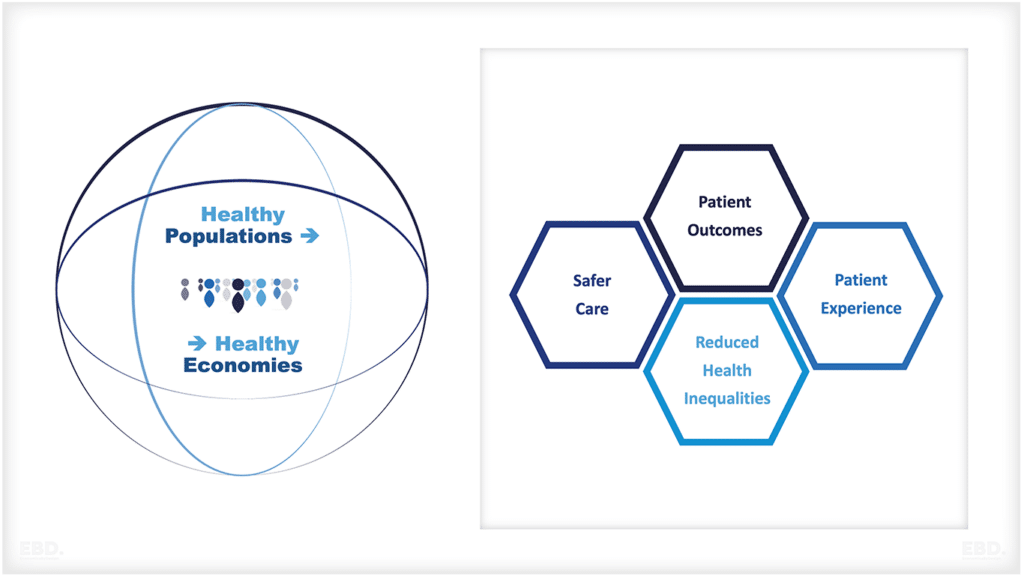

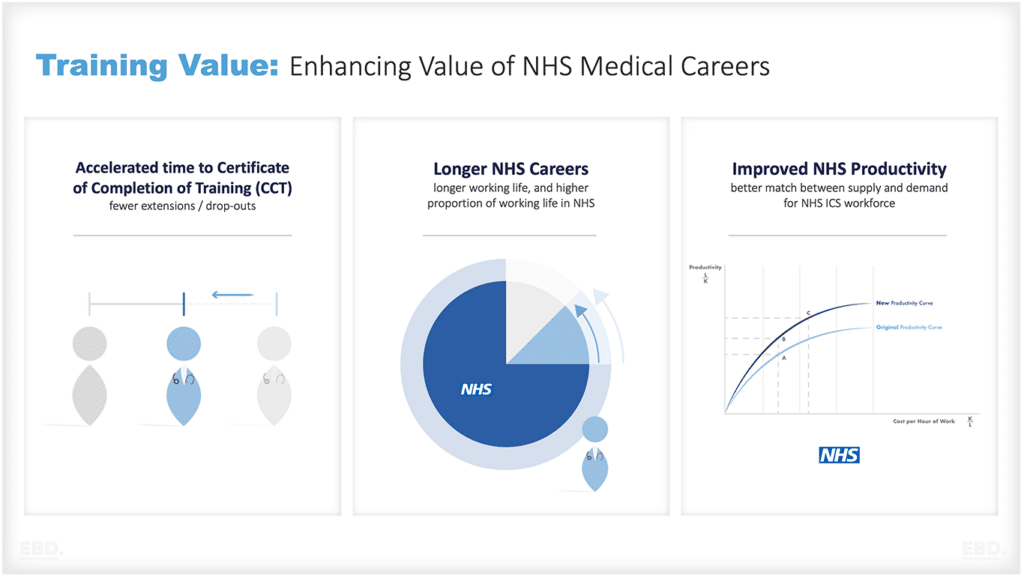

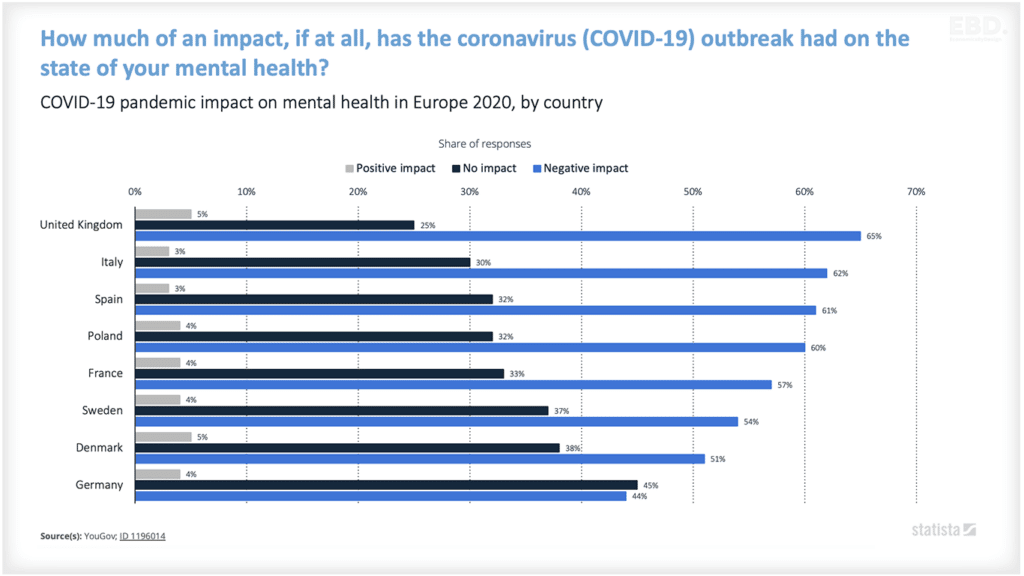

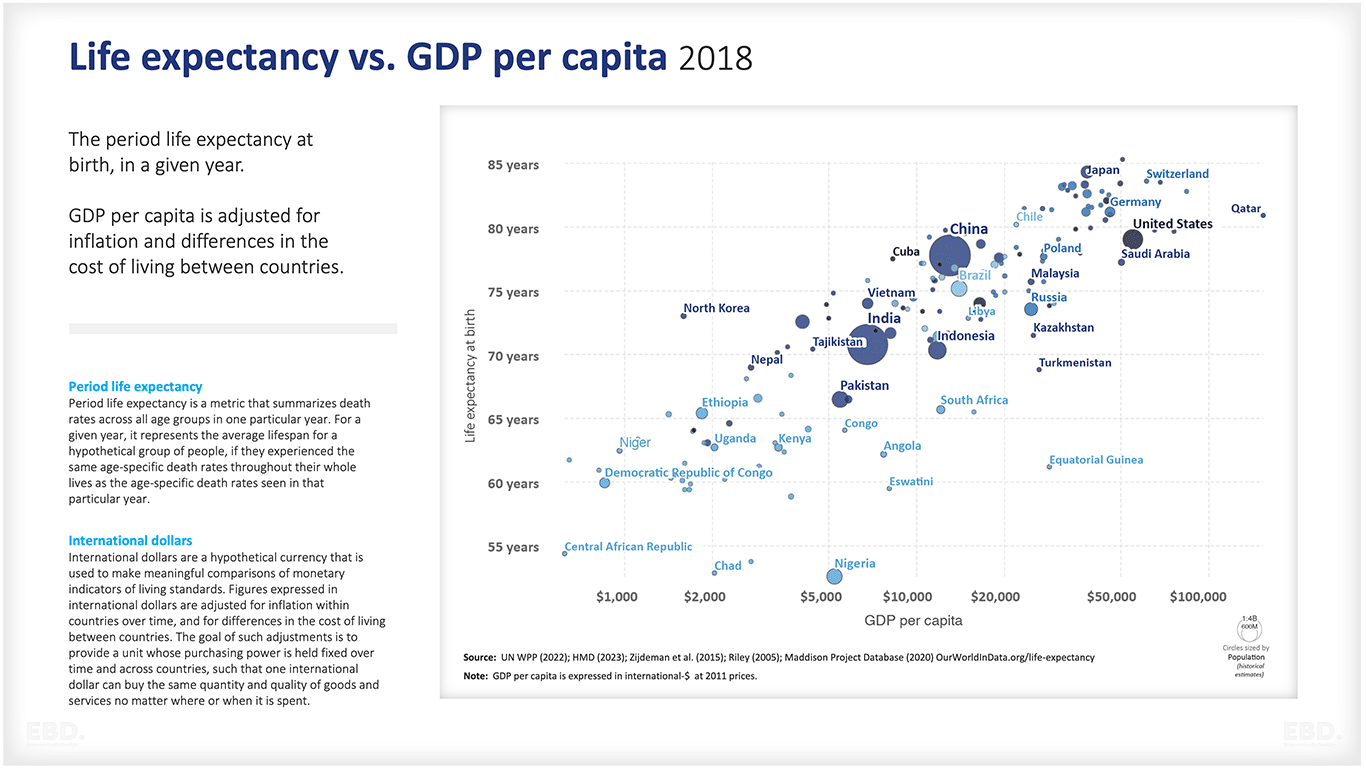

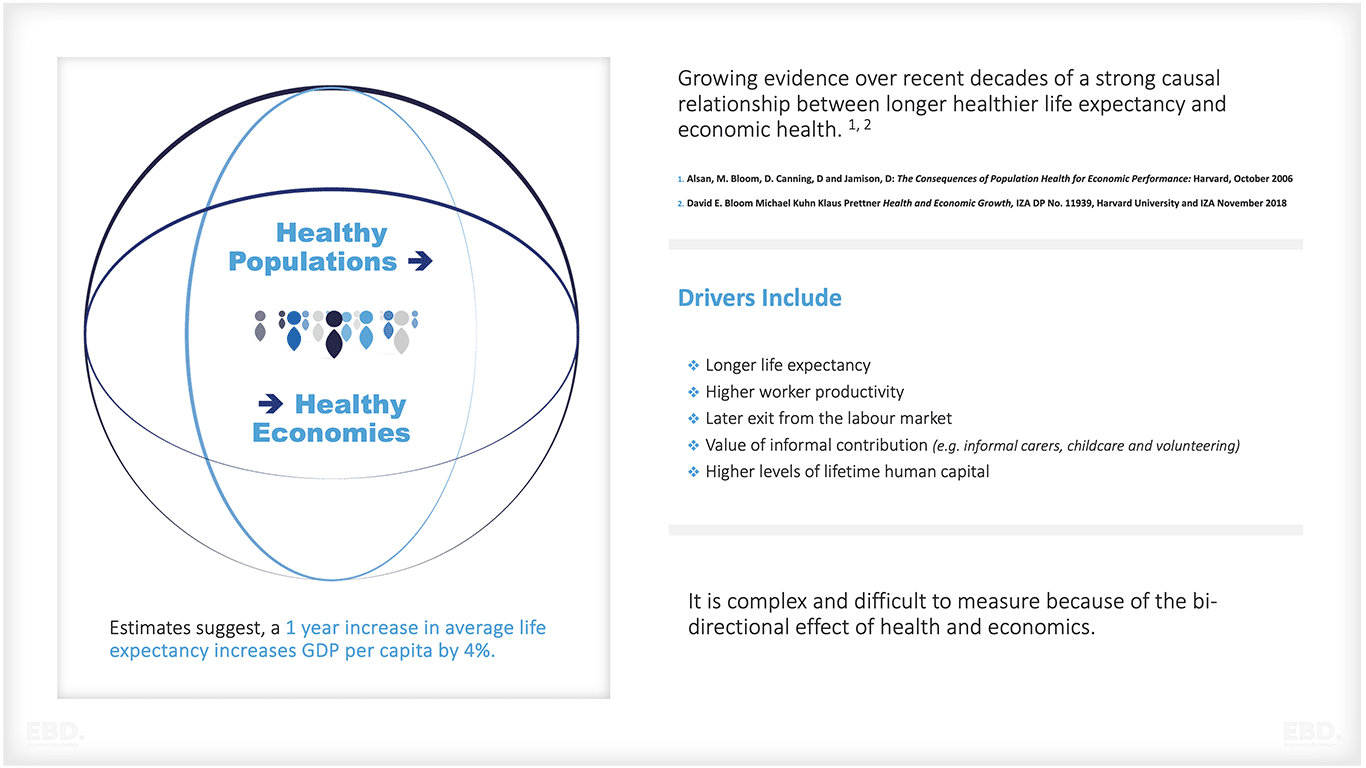

In this economic lens, I explore the potential value of incorporating workforce productivity as a measure in health economics to inform prioritization of health benefit packages. As is illustrated in the figure below, the well-being of a country’s population significantly influences its economic growth and development.

Poor health can impede economic productivity, while investments in healthcare can enhance overall population health and contribute to economic growth. Considering the impact of healthcare interventions on workforce productivity holds significance not only for individual employers but also for the overall economic progress of a nation.

Some argue that the primary objective of the healthcare system is to achieve health. However, in this article, I posit that the scope of the healthcare system should extend beyond health alone and encompass the reduction of economic costs associated with illness and disease. Consequently, healthcare system goals should encompass two objectives: improving society’s health and strengthening society’s economy (Brock, 2003).

What Is Cost Effectiveness Analysis in Health?

Health systems are not like normal markets. It is difficult to measure value in the absence of a market price and for these reasons concepts like Value Based Care have developed which incorporate wider measures of value. Health economists have, as a result developed methods to measure cost effectiveness of health interventions to support decisions to invest and to prioritise health spending.

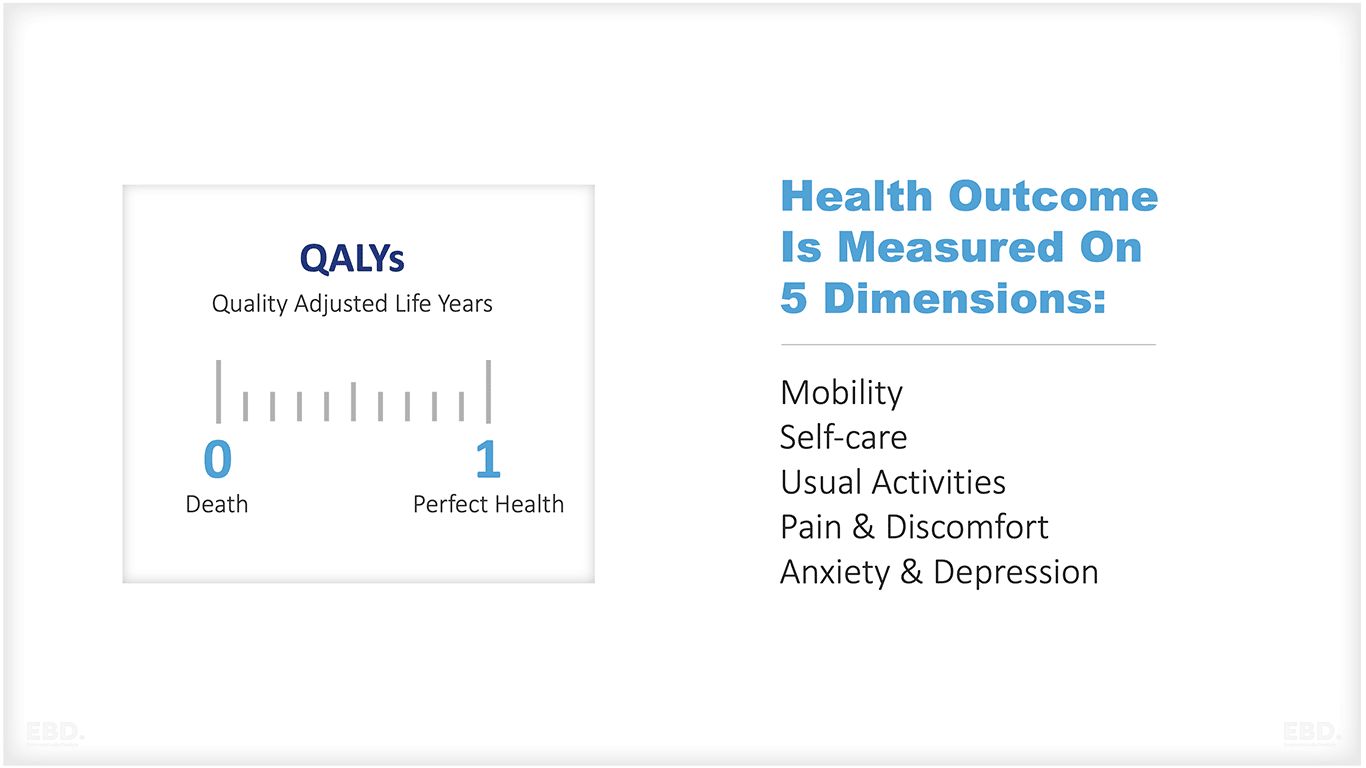

Utility measures of value such as the Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY) or the Disability Adjusted Life Year (DALY) are used to measure intervention outcomes. Costs of interventions are compared on the basis of their cost per QALY or cost per DALY achieved. Cost effectiveness is determined by comparing these with no treatment or usual treatment often presented as Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratios (ICER).

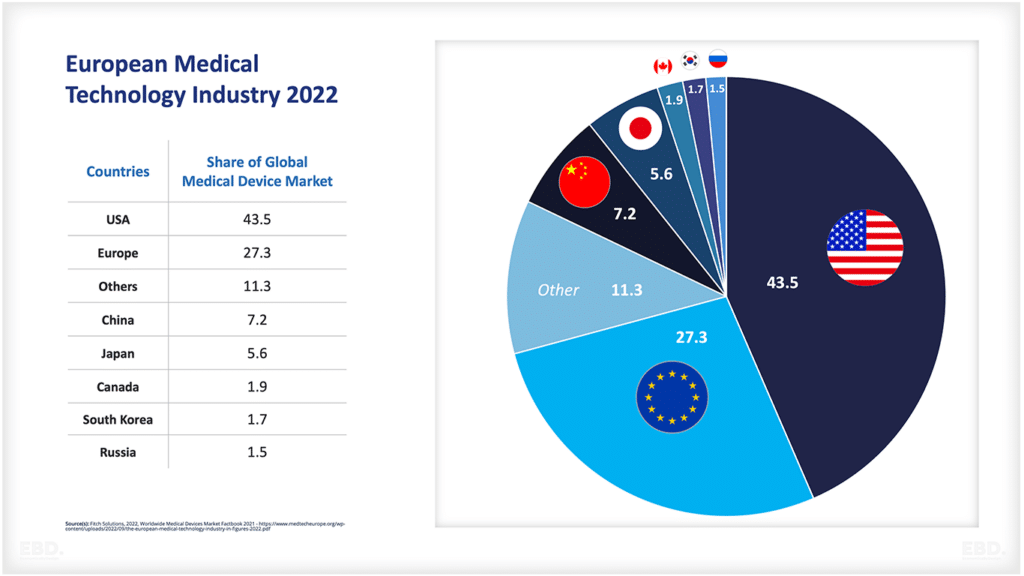

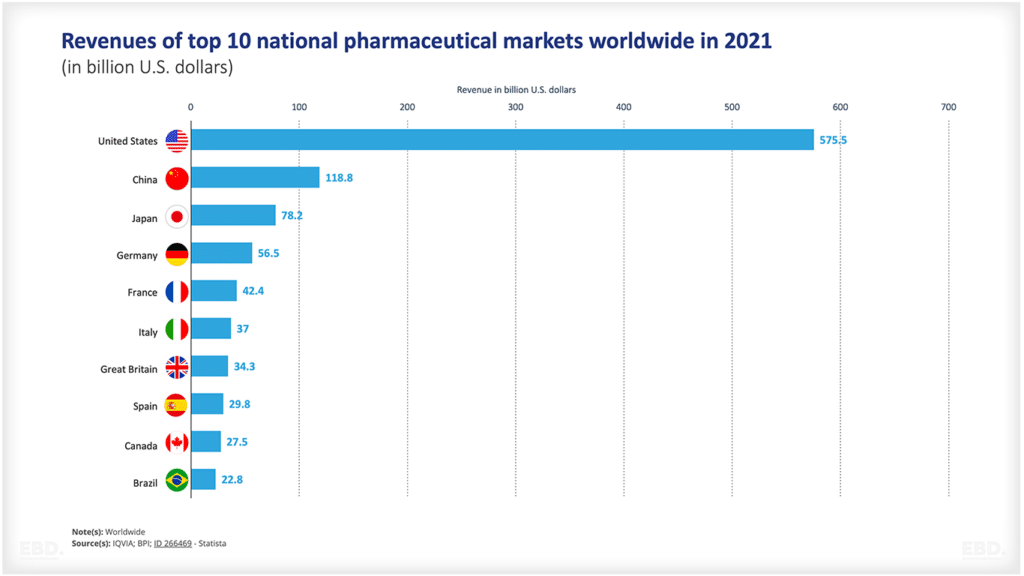

The costs of different treatment interventions vary from country to country. Local pay rates, infrastructure costs, supply chains, and economic circumstances all contribute to the affordability of imported drugs and medical devices, creating a diverse investment context.

Additionally, countries often establish a local cost-effectiveness “threshold” to determine the value of an intervention relative to competing funding priorities. Consequently, many countries rely on health economists to guide decisions on health benefit priorities, rather than depending on analysis from other countries.

The extent of cost-effectiveness analysis varies across different countries. As highlighted by Lindholm et al. (2008), one of the ongoing methodological debates in the literature revolves around the choice of perspective – whether it should be a healthcare or societal perspective.

Some argue that decision-makers should prioritize maximizing population health within the healthcare budget, focusing solely on costs incurred by the healthcare system. On the other hand, others assert that decision-makers, guided by economic evaluations, should aim to maximize social welfare, considering costs beyond the healthcare budget as equally significant (Drummond et al., 2005; Gold et al., 1996; Krol & Brouwer, 2014).

Cost Effectiveness Analysis in Low- or Middle-Income Countries

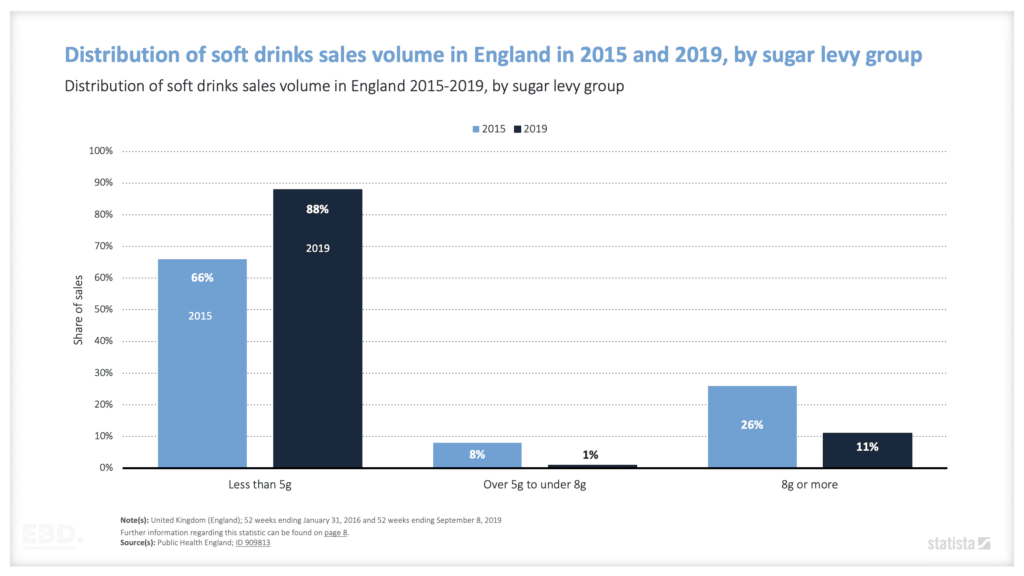

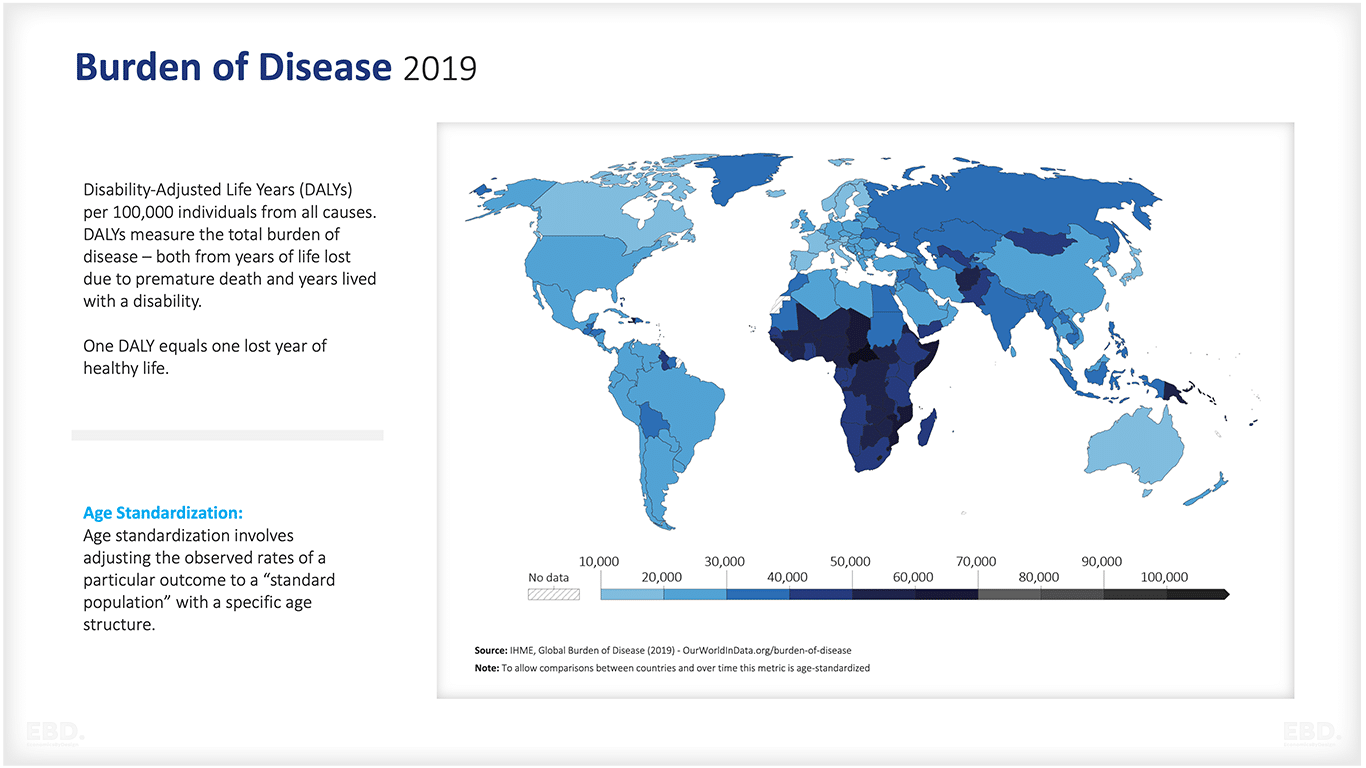

In Low- or Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), there has been a notable increase in the production and utilization of economic evaluations for priority setting in the past two decades (Pitt et al., 2016). The figure below shows the disproportionate share of burden of disease experienced by Low- or Middle-Income Countries.

Identifying the most cost-effective interventions targeted to reducing the burden of disease in LMICs is thus vital for both health and sustainable economic growth.

However, conducting such evaluations can be challenging and costly for LMICs, given the lack of availability of data. In such cases, it is often recommended to rely on international databases that provide cost-effectiveness information for various healthcare interventions. This approach helps ensure the use of objective and reliable data in decision-making processes.

One such database is the Tufts Global Health CEA Registry a database that focusses on cost effectiveness of interventions designed to mitigate burden of disease. The registry includes studies on a wide range of topics, including HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, maternal and child health, non-communicable diseases, and health system strengthening which provide information on the costs of health interventions.

Another example is the World Health Organisation Universal Health Coverage Compendium Cost-Effectiveness Data. The portal contains data on the cost-effectiveness of interventions for a variety of health outcomes, such as cancer, mental health, and communicable diseases. These resources can help LMICs make informed decisions about which health interventions to prioritize based on their specific context and needs.

However, there is a limitation in utilizing these studies due to the absence of consensus on standard guidelines for both methodology and reporting in LMICs. In practice, there is limited comparability across studies, even within the same context, which poses challenges in their consideration for decision-making (Griffiths et al., 2016; Luz et al., 2018).

Why is it Important to include Productivity in Health Priority Setting in LMICs?

Very few studies of the health economics of an intervention include the economic impact on workforce productivity.

When prioritizing health in LMICs, it is important to consider a societal perspective that encompasses both healthcare and productivity. This does not imply giving priority solely to the “young”, but rather recognizing the value of health to the broader economy as one of many factors to consider.

Decision-makers should adopt an objective and professional approach while retaining the original meaning of the argument.

By considering productivity in resource allocation decisions, policymakers acknowledge that certain interventions hold inherent value as they contribute more to productivity, thereby fostering additional economic growth and other non-health benefits.

Consequently, these factors can enhance societal welfare through mechanisms like the tax system or other transfer mechanisms (Murray, 1996; Murray & Acharya, 1997; Neumann et al., 2021; Yuasa et al., 2021).

The rationale for including productivity as a factor is rooted in utilitarian philosophy, which posits that the goal of society is to maximize utility. Therefore, a state with a higher sum of utility is always preferable to a state with a lower sum.

As argued by Brock (2003), the previous approach to DALY estimation placed greater emphasis on the productive middle years of life, assigning more weight to life years during this period compared to childhood or older age. This was based on the rationale that children and the elderly often rely on individuals in their productive middle years for economic, social, and psychological support. Consequently, the previous approach indirectly favored the ‘young’ by considering the non-health burdens of disease, even though DALY developers claimed that differentiation was based solely on age and sex (Murray, 1996).

The case for including productivity is most apparent in scenarios where health interventions yield significant indirect non-health benefits, sometimes even overshadowing their direct health benefits. As illustrated by Brock (2003), substance abuse interventions serve as a fitting example.

Substance abuse treatment programs offer advantages that extend beyond the improved quality and duration of life for individuals struggling with substance abuse. These programs also generate productivity benefits by enabling individuals to return to work, thereby reducing the economic, social, and psychological burden of their substance abuse on their families.

When advocating for the prioritization of substance abuse treatment programs, the consideration of these indirect and non-health benefits carries significant weight.

Considering productivity in resource allocation becomes even more crucial in LMICs, where social security is limited compared to settings with (close to) universal health coverage (Griffiths et al., 2016). LMICs face the challenge of addressing the “double burden of disease”.

Productivity costs and losses are significantly higher for chronic conditions. Failing to accurately measure the true value of interventions can have dire consequences in these contexts, particularly when patients bear a substantial proportion of the costs through high out-of-pocket expenses (Griffiths et al., 2016).

The Lancet NCDI Poverty Commission highlights that out-of-pocket expenditures and productivity loss resulting from NCDIs have a profound impact on household impoverishment (Bukhman et al., 2020). In fact, the reduction in household income caused by NCDs is more than twice as impoverishing as the impact of general health conditions (Mwai & Muriithi, 2016).

What Are the Challenges and Issues of including Productivity in Health Priority Setting in LMICs?

Moral Issues

The primary moral objection to including productivity when allocating resources is rooted in the principle of fairness. If individuals’ health needs are equally important and their treatments are equally effective, then all else being equal, they have an equal right to have those needs met.

For instance, prioritizing treatment for a working-age group of patients over a group of retired patients based on their potential economic benefits for their employer and society as a whole may be a reason to prefer them, but it may not necessarily be fair. It fails to acknowledge the retired patients’ equal entitlement to treatment (Brock, 2003; Voorhoeve, 2019).

In allocation/prioritization decisions at a disease (macro) level, the argument of fairness becomes less defensible. Let us consider the example of hypertension detection, management, and control programs. In recent years, there has been a significant increase in Blood Pressure (BP) levels in LMICs, with only 1 in 3 individuals being aware of their hypertension status and a mere 8% having their BP levels under control (Schutte et al., 2021).

This not only impacts mortality rates but also widens the health equity gap, contributes to economic hardships for patients and carers, and increases costs to the national health systems. These systems already face challenges such as low physician-to-patient ratios and lack of access to medicines (Schutte et al., 2021).

While Akpa et al.’s (2020) age-standardized analysis has shown that hypertension is more prevalent in men than women, it is important to note that hypertensive disorders have been identified as the second leading cause of maternal and perinatal mortality.

Chronic hypertension can increase the risk of developing preeclampsia during pregnancy by 3- to 1-fold (Parati et al., 2022). As such, one can argue that prioritizing hypertension detection, management, and control programs while considering their associated productivity losses does not discriminate against women.

Non-communicable diseases and injuries (NCDIs), while often portrayed as complications of ageing and development, impose a significant and varied disease burden on children and young adults in LMICs. A substantial portion of this burden stems from the fact that NCDIs are contracted at a younger age by the poorest individuals (partly due to population structure).

Moreover, these conditions prove more fatal for those already living in poverty (Bukhman et al., 2020). NCDIs are responsible for the majority of disability among the poorest (accounting for 71% of years lived with disability).

The economic impact of NCDIs on household productivity is particularly challenging as it further impoverishes those who are already in poverty (Bukhman et al., 2020).

While considering productivity in priority setting, decision makers may be perceived as discriminating against older individuals. This discrimination adds to the existing disparities resulting from the current approach to DALY estimation, as the death of a younger person contributes more to the burden of disease compared to that of an older individual (Murray & Schroeder, 2020).

Nevertheless, excluding productivity in priority setting undermines the growth of public resources that can be allocated towards future healthcare for vulnerable groups, such as the elderly or the most disadvantaged (Lindholm et al., 2008).

The worst-off can be defined as individuals with health conditions that result in premature death among the young or the poor, as well as those with conditions that significantly hinder their autonomy and equal citizenship (Voorhoeve, 2019). However, according to the literature, the worst-off are also characterized by having less health service coverage, lower life expectancies compared to the reference group, greater disease severity, substantial disease burden, previous health losses, lower socioeconomic status, and belonging to minority groups based on gender, race, religion, or sexual orientation (Norheim, 2016; Norheim et al., 2014; Norheim et al., 2019; Kapiriri & Razavi, 2022).

Neumann et al. (2021) advocate for the implementation of value-based pricing in vaccines and treatments, even during a pandemic. They acknowledge that some may be hesitant to accept the idea that pharmaceutical companies could generate significant profits during such times.

However, they argue that this approach is crucial in order to foster innovation and ensure a greater availability of solutions for future pandemics. Similarly, when considering health priority setting at a macro level, the inclusion of productivity as a factor should not be seen as discriminatory towards the elderly.

Instead, decision makers can use this information to allocate increased public resources towards their care in a fair and equitable manner.

Social Productivity

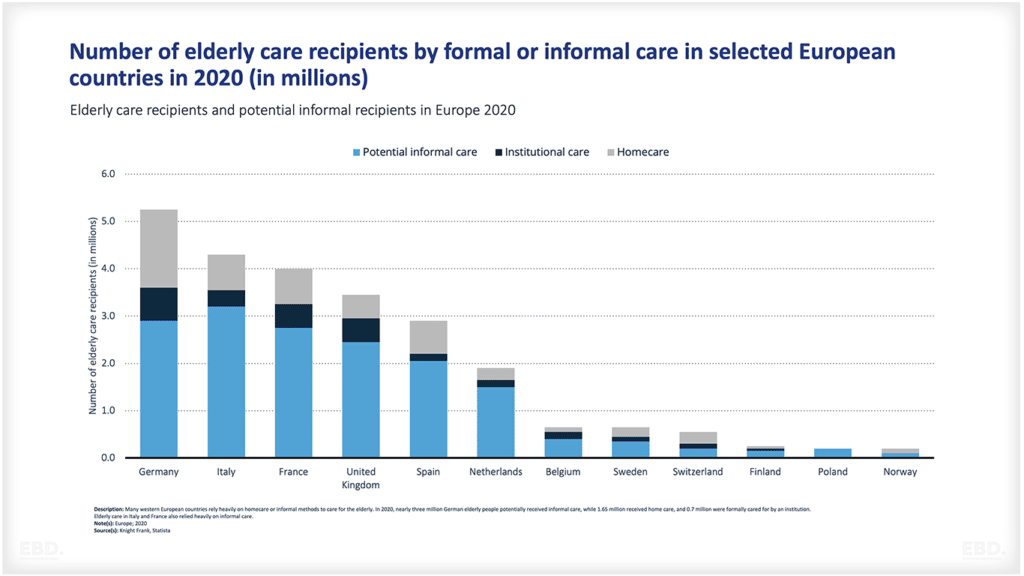

It is important to emphasize that changes in productivity can occur in both paid and unpaid work contexts (Krol & Brouwer, 2014). Unpaid work, despite its lack of market value, holds significant economic value as it contributes to the welfare of society. According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO 2018) unpaid work accounts for the equivalent of 2 billion people working 8 hours per day globally.

By considering productivity in relation to unpaid work, such as household tasks (cooking, cleaning, etc.), caregiving (elderly or childcare), and volunteer work (community health worker, for example), we can avoid ethical concerns related to discrimination against diseases prevalent among groups with a larger proportion of unpaid work, such as women and the elderly (Krol & Brouwer, 2014).

This approach ensures that productivity is not solely based on economic factors but also recognizes the instrumental role these vulnerable groups play in the functioning of their communities and wider networks. When making priority setting decisions, social productivity classification is given equal consideration to economic productivity.

Methodological Issues

There are various methodological issues associated with how productivity is measured. Therefore, while I advocate for its inclusion in priority setting criteria, it is important to consider the following factors.

For instance, when using the human capital approach, any potential production not carried out by an individual due to illness or premature mortality is considered a loss in productivity (Neumann et al., 2016; Turner et al., 2021; Yuasa et al., 2021). On the other hand, the friction cost approach limits productivity losses to the time required to replace an ill employee and train a new one (friction period) (Riewpaiboon, 2014; Turner et al., 2021; Williams, 1992).

It has been suggested that the human capital approach overestimates the value of lost production, as it assumes full employment and does not account for the loss of employment when replacing an ill person with another (Krol & Brouwer, 2014). Moreover, the valuation of productivity losses varies, including considerations such as taxes, employer-paid benefits, and accounting for future wage growth, which have been subjects of debate (Turner et al., 2021).

In addition to the quantification of productivity losses, the valuation methods also differ. It is worth noting that research capacity and funding for economic evaluations are limited in LMICs (Pitt et al., 2016), which further complicates the consideration of productivity in priority setting within these settings.

Recommendations for Including Productivity in Health Economics Studies in LMICs

Capturing productivity benefits as a separate criterion in the decision-making process is vital. This allows for the consideration of productivity costs/gains, which can be assigned a lesser weight compared to health benefits, rather than giving them equal weight or no weight at all (Brock, 2003).

The decision of how much weight to assign to productivity benefits should be left to the discretion of decision makers in each country. This reflects the unique context of each country, but the choice needs to be explicit.

As illustrated in the figure below, productivity is the critical link between healthy populations and healthy economies. To ignore it when setting priorities for healthcare interventions would miss opportunities for using health policy to improve overall societal wellbeing.

In conclusion, considering the complex burden of disease and the budgetary constraints faced by LMICs, including productivity as a distinct criterion in health priority setting would enhance decision making.

Bibliography

Akpa, O. M., Made, F., Ojo, A., Ovbiagele, B., Adu, D., Motala, A. A., Mayosi, B. M., Adebamowo, S. N., Engel, M. E., Tayo, B., Rotimi, C., Salako, B., Akinyemi, R., Gebregziabher, M., Sarfo, F., Wahab, K., Agongo, G., Alberts, M., Ali, S. A., … as members of the CVD Working Group of the H3Africa Consortium. (2020). Regional Patterns and Association Between Obesity and Hypertension in Africa: Evidence From the H3Africa CHAIR Study. Hypertension, 75(5), 1167–1178. //doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14147

Brock, D. W. (2003). Separate spheres and indirect benefits. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation, 1(1), 4. //doi.org/10.1186/1478-7547-1-4

Bukhman, G., Mocumbi, A. O., Atun, R., Becker, A. E., Bhutta, Z., Binagwaho, A., Clinton, C., Coates, M. M., Dain, K., Ezzati, M., Gottlieb, G., Gupta, I., Gupta, N., Hyder, A. A., Jain, Y., Kruk, M. E., Makani, J., Marx, A., Miranda, J. J., … Wroe, E. B. (2020). The Lancet NCDI Poverty Commission: Bridging a gap in universal health coverage for the poorest billion. The Lancet, 396(10256), 991–1044. //doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31907-3

Chisholm, D., & Evans, D. B. (2007a). Economic evaluation in health: Saving money or improving care? Journal of Medical Economics, 10(3), 325–337. //doi.org/10.3111/13696990701605235

Drummond, M. F., Sculpher, M. J., Torrance, G. W., O’Brien, B. J., & Stoddart, G. L. (2005). Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programme. Third edition. Oxford University Press.

Gold, M. R., Siegel, J. E., Russell, L. B., & Weinstein, M. C. (Eds.). (1996). Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. Oxford University Press.

Griffiths, U. K., Legood, R., & Pitt, C. (2016). Comparison of Economic Evaluation Methods Across Low‐income, Middle‐income and High‐income Countries: What are the Differences and Why? Health Economics, 25(Suppl Suppl 1), 29–41. //doi.org/10.1002/hec.3312

Guaraldi, G., Zona, S., Menozzi, M., Carli, F., Bagni, P., Berti, A., Rossi, E., Orlando, G., Zoboli, G., & Palella, F. (2013). Cost of noninfectious comorbidities in patients with HIV. ClinicoEconomics and Outcomes Research: CEOR, 5, 481–488. //doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S40607

Ham, C., & Coulter, A. (2001). Explicit and implicit rationing: Taking responsibility and avoiding blame for health care choices. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 6(3), 163–169. //doi.org/10.1258/1355819011927422

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHMME). GDB Compare. Seattle, WA: 2015. Available from //vizhub.healthdata.org/gdb-compare (Accessed September 13,2022)

International Labour Organisation (ILO). Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work (2018). //www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_633166.pdf (Accessed November 2023)

Harper, K., & Armelagos, G. (2010). The Changing Disease-Scape in the Third Epidemiological Transition. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7(2), Article 2. //doi.org/10.3390/ijerph7020675

Kapiriri, L., & Martin, D. K. (2007). A strategy to improve priority setting in developing countries. Health Care Analysis: HCA: Journal of Health Philosophy and Policy, 15(3), 159–167. //doi.org/10.1007/s10728-006-0037-1

Kapiriri, L., Norheim, O. F., & Martin, D. K. (2009). Fairness and accountability for reasonableness. Do the views of priority setting decision makers differ across health systems and levels of decision making? Social Science & Medicine, 68(4), 766–773. //doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.11.011

Kapiriri, L., & Razavi, S. D. (2022). Equity, justice, and social values in priority setting: A qualitative study of resource allocation criteria for global donor organizations working in low-income countries. International Journal for Equity in Health, 21(1), 17. //doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01565-5

Kaur, G., Prinja, S., Lakshmi, P. V. M., Downey, L., Sharma, D., & Teerawattananon, Y. (2019). Criteria Used for Priority-Setting for Public Health Resource Allocation in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 35(6), 474–483. //doi.org/10.1017/S0266462319000473

Klasing, M. J., & Milionis, P. (2020). The international epidemiological transition and the education gender gap. Journal of Economic Growth, 25(1), 37–86. //doi.org/10.1007/s10887-020-09175-6

Koopmanschap, M., Burdorf, A., Jacob, K., Meerding, W. J., Brouwer, W., & Severens, H. (2005). Measuring productivity changes in economic evaluation. PharmacoEconomics,23(1), 47–54. //doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200523010-00004

Klebanov, N. (2018). Genetic Predisposition to Infectious Disease. Cureus, 10(8), e3210. //doi.org/10.7759/cureus.3210

Krol, M., & Brouwer, W. (2014). How to Estimate Productivity Costs in Economic Evaluations. PharmacoEconomics, 32(4), 335–344. //doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0132-3

Lindholm, L., Löfroth, E., & Rosén, M. (2008). Does productivity influence priority setting? A case study from the field of CVD prevention. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation : C/E, 6, 6. //doi.org/10.1186/1478-7547-6-6

Luz, A., Santatiwongchai, B., Pattanaphesaj, J., & Teerawattananon, Y. (2018). Identifying priority technical and context-specific issues in improving the conduct, reporting, and use of health economic evaluation in low- and middle-income countries. Health Research Policy and Systems, 16(1), 4. //doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0280-6

Murray, C. J. L., & Acharya, A. K. (1997). Understanding DALYs. Journal of Health Economics, 16(6), 703–730. //doi.org/10.1016/S0167-6296(97)00004-0

Murray, C. J., Ezzati, M., Flaxman, A. D., Lim, S., Lozano, R., Naghavi, M., Salomon, J. A.,

Shibuya, K., Vos, T., Wikler, D., & Lopez, A. D. (2010). Comprehensive Systematic Analysis of Global Epidemiology: Definitions, Methods, Simplification of DALYs, and Comparative Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. 141.

Neumann, P. J., Cohen, J. T., Kim, D. D., & Ollendorf, D. A. (2021). Consideration Of Value-Based Pricing For Treatments And Vaccines Is Important, Even In The COVID-19 Pandemic: Study reviews alternative pricing strategies (cost-recovery models, monetary prizes, advanced market commitments) for COVID-19 drugs, vaccines, and diagnostics. Health Affairs, 40(1), 53–61. //doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01548

Norheim, O. F., Baltussen, R., Johri, M., Chisholm, D., Nord, E., Brock, D., Carlsson, P., Cookson, R., Daniels, N., Danis, M., Fleurbaey, M., Johansson, K. A., Kapiriri, L., Littlejohns, P., Mbeeli, T., Rao, K. D., Edejer, T. T.-T., & Wikler, D. (2014). Guidance on priority setting in health care (GPS-Health): The inclusion of equity criteria not captured by cost-effectiveness analysis. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation, 12(1), 18. //doi.org/10.1186/1478-7547-12-18

Parati, G., Lackland, D. T., Campbell, N. R. C., Ojo Owolabi, M., Bavuma, C., Mamoun Beheiry, H., Dzudie, A., Ibrahim, M. M., El Aroussy, W., Singh, S., Varghese, C. V., Whelton, P. K., Zhang, X.-H., & on behalf of the World Hypertension league. (2022). How to Improve Awareness, Treatment, and Control of Hypertension in Africa, and How to Reduce Its Consequences: A Call to Action From the World Hypertension League. Hypertension, 79(9), 1949–1961. //doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.18884

Pitt, C., Goodman, C., & Hanson, K. (2016). Economic Evaluation in Global Perspective: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Recent Literature: Economic Evaluation in Global Perspective. Health Economics, 25, 9–28. //doi.org/10.1002/hec.3305

Pitt, C., Vassall, A., Teerawattananon, Y., Griffiths, U. K., Guinness, L., Walker, D., Foster, N., & Hanson, K. (2016). Foreword: Health Economic Evaluations in Low‐ and Middle‐income Countries: Methodological Issues and Challenges for Priority Setting. Health Economics, 25(Suppl Suppl 1), 1–5. //doi.org/10.1002/hec.3319

Riewpaiboon, A. (2014). Measurement of costs for health economic evaluation. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet Thangphaet, 97 Suppl 5, S17-26.

Schutte, A. E., Venkateshmurthy, N. S., Mohan, S., & Prabhakaran, D. (2021). Hypertension in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Circulation Research, 128(7), 808–826. //doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.318729

Turner, H. C., Archer, R. A., Downey, L. E., Isaranuwatchai, W., Chalkidou, K., Jit, M., & Teerawattananon, Y. (2021). An Introduction to the Main Types of Economic Evaluations Used for Informing Priority Setting and Resource Allocation in Healthcare: Key Features, Uses, and Limitations. Frontiers in Public Health, 9. //www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.722927

Voorhoeve, A. (2019). Why Health-Related Inequalities Matter and Which Ones Do. In O. F.

Norheim, E. J. Emanuel, & J. Millum (Eds.), Global Health Priority-Setting: Beyond Cost-Effectiveness (p. 0). Oxford University Press. //doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190912765.003.0009

Williams, A. (1992). Cost-effectiveness analysis: Is it ethical? Journal of Medical Ethics, 18(1), 7–11.

Yuasa, A., Yonemoto, N., LoPresti, M., & Ikeda, S. (2021). Productivity loss/gain in cost-effectiveness analyses for vaccines: A systematic review. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 21(2), 235–245. //doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2021.1881484