Health Economic Analysis + Health Outcomes

In Jacqueline Mallender’s introduction to the Economic Lens series, she writes:

“Health economists can add value to the healthcare system by improving our understanding of how it works and by making recommendations on how to improve its efficiency and effectiveness.”

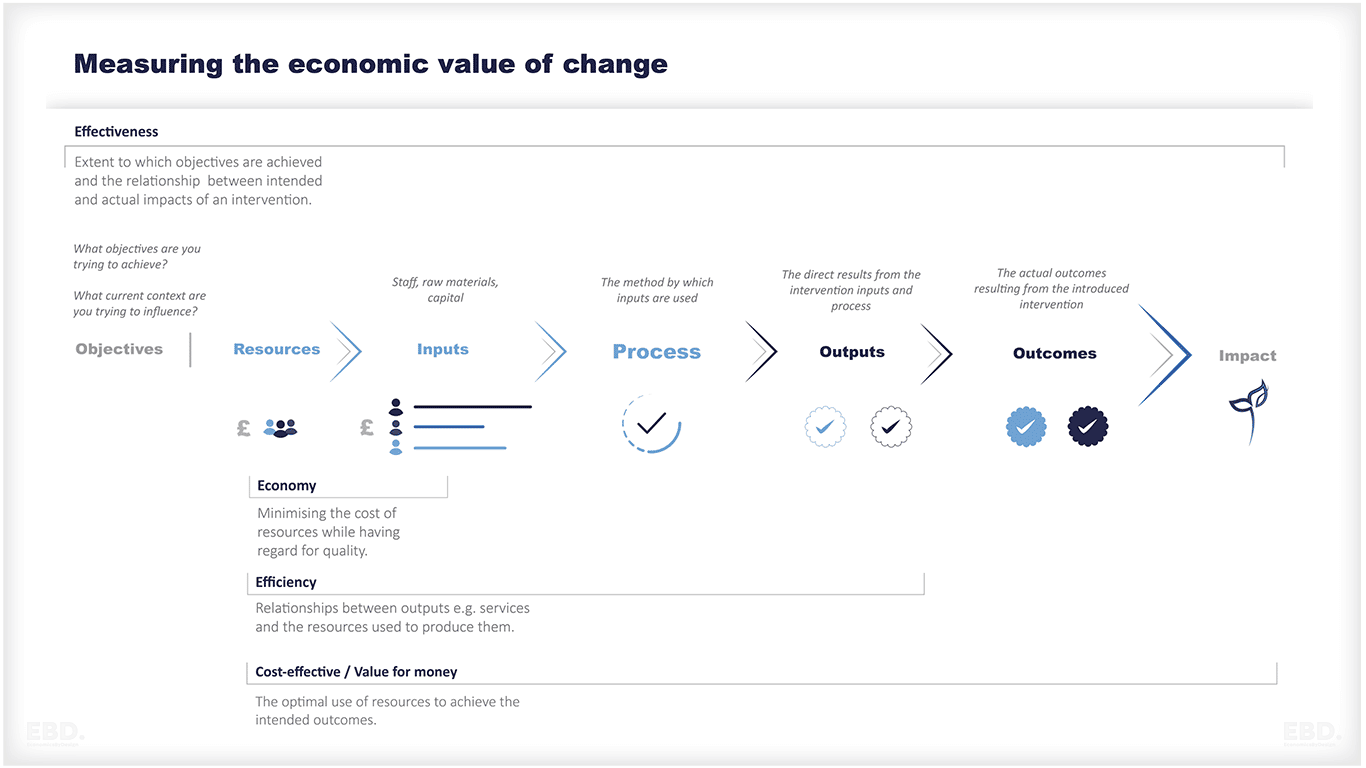

A look at the Economic Lens articles by Economics By Design shows that concepts such as ‘effectiveness’, ‘efficiency’, ‘productivity’ and ‘value’ are central to an economic approach to improving decision making in health care.

One thing these terms all share is that they are all grounded in often implicit assumptions about the relationships between resource consuming actions on the one hand and one or more of their consequences i.e. outcomes on the other.

Michael Porter, a professor at the Harvard Business School is credited with focussing health care systems on value. He argues that the purpose of a health care system is to maximise value.

Porter defines value as: “the health outcomes achieved per dollar spent” and in 2013, the International Institute for Health Outcome Measurement that he established defined health outcomes as “the results people care about most including the ability to live normal, productive lives”…which begs the questions ‘which people?’ and ‘what do they most care about?’.

Unsurprisingly, there is no one single right answer.

In this economics lens, I share some observations about

- the nature of outcomes in health care and health systems and

- the attribution of outcomes to inputs and process.

I also put forward six key questions about health outcomes that decision makers in healthcare may want to consider whenever they encounter health economic analyses.

What assumptions do health economists make about health outcomes?

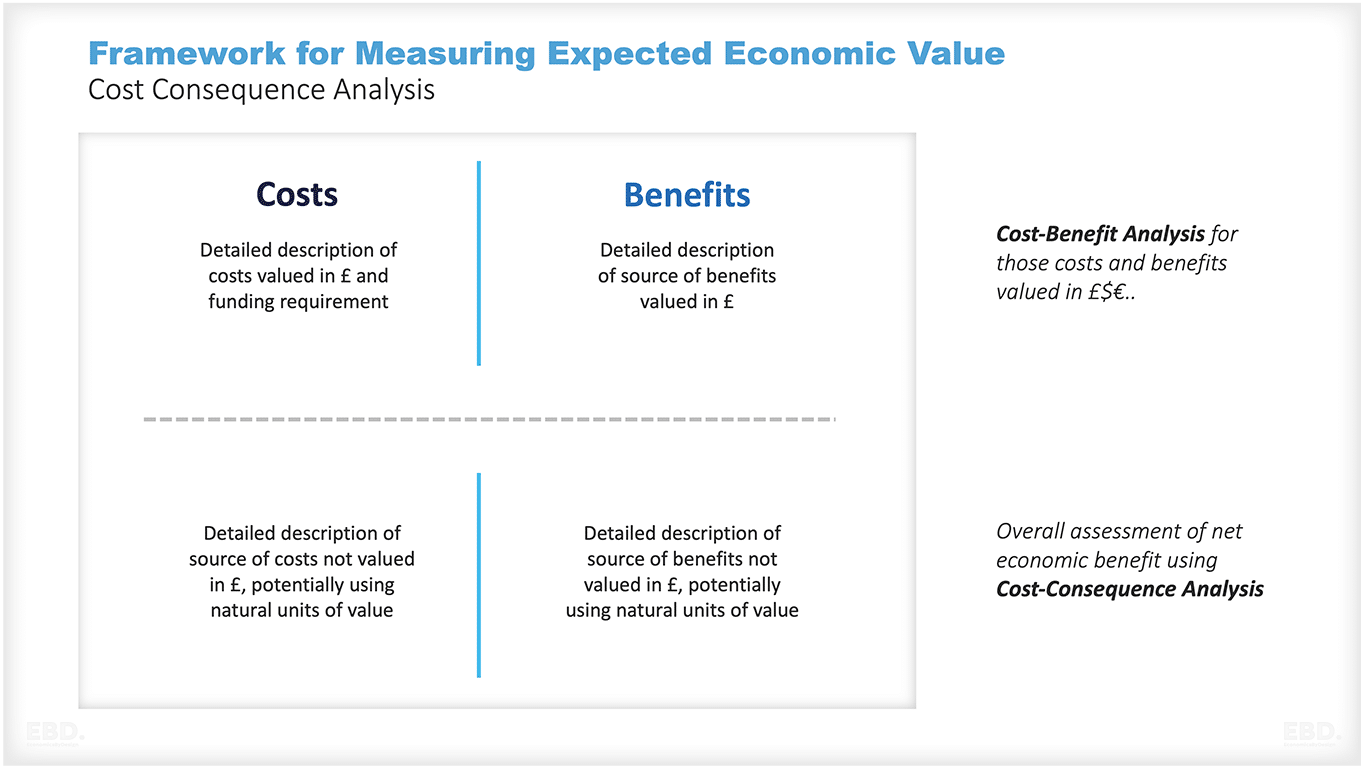

It’s helpful to understand the implicit assumptions that underpin any health economic analysis that incorporates health outcomes. To make the best use of health economic analysis, you need to understand:

- Which outcomes have been included? You need to know or work out which outcomes are being taken into account in the analysis. It is common for economic analysis to be based on an assumption that more activity generates more benefits rather than harms but this is not always the case.

- Whether the outcomes are relevant? You need to know whether you think the outcomes are relevant and appropriate for the circumstances in question. It is possible that important outcomes that are hard to measure have been missed in favour of those that are easier to measure.

- How the outcomes were generated? You need to consider the assumptions being made that relate changes in input and process to changes in outcome and whether these are valid or not. Economic analysis should include outcomes that are directly and predictably attributable to defined interventions but this may not always be the case.

Any quantitative value of concepts such as efficiency, value etc will vary with the outcome chosen, the accuracy and completeness of its measurement, and the validity of our understanding of the link between inputs and outcomes.

It is easy to think that everyone agrees what the important outcomes of healthcare are and what they should be. It’s also easy to think that the important outcomes of health care systems are readily identified and measured. And it’s easy to think that a change in outcome is readily attributable to a particular change in input or process. All these things turn out not to be true.

That doesn’t invalidate the importance of considering outcomes or of using economic principles to inform decision making, but, as with all other forms of quantitative and qualitative decision support, it’s important to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the approaches and methods being used and to remember that although models, analyses and algorithms can support decision making, decision makers may still have to make difficult value laden judgements that go beyond the technical models when making their decisions.

Using an ethical framework alongside economic and other forms of analytic tools can often be helpful.

What are the 6 questions that should be asked every time health economic analysis is used for decision making?

Here are the questions that I think are worth thinking about every time one comes across health economic analysis where outcomes are relevant…which is every time an outcome is referred to explicitly or implicitly e.g. in reference to efficiency, effectiveness, value , productivity and more:

Question 1: What are the outcomes implied or explicit in any particular scenario?

Sometimes it’s obvious and uncontested. For example, most people would agree that, everything else being equal, reducing premature mortality is a desirable outcome. But it’s not always that obvious. For example, what outcome is being referred to when H.M. Treasury grumbles that health care productivity needs to improve.

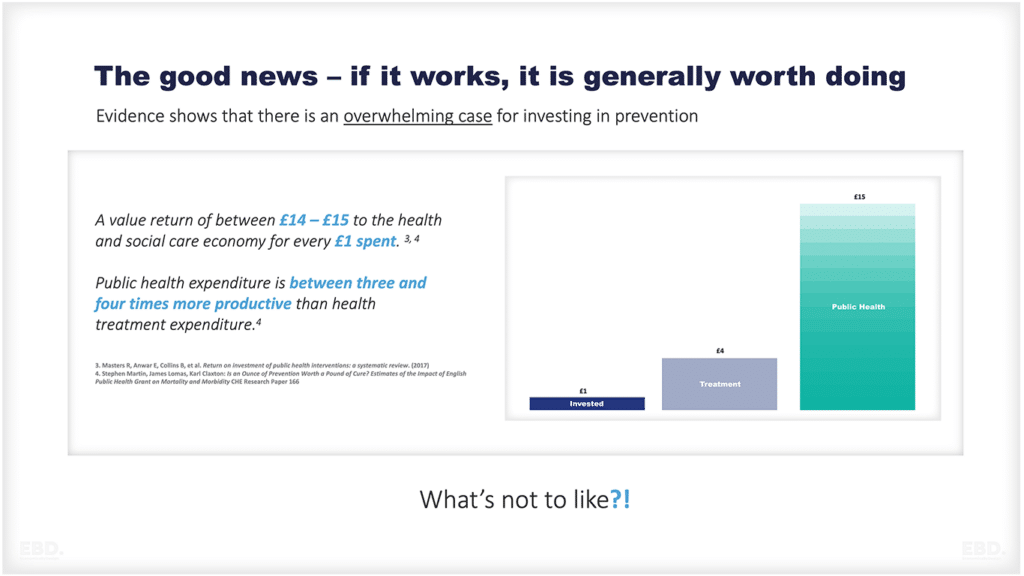

Some may say the outcome HMT is looking for is that more people should be in better health for every unit of health care resource consumed. If that’s the case, then a rational approach to improving productivity would be to invest more in cost-effective prevention and disinvest in less cost-effective expensive surgery.

Others might say that HMT sees better productivity as the health service performing more operations at lower cost per case, in which case approaches that lower the unit cost of even ineffective surgery would be a rational way to approach improving productivity.

Or perhaps they mean the health service should be reducing the number of people unable to work because of ill health, which would prompt another different set of responses.

Whatever the answer, the rational response to improving productivity depends on the nature of the outcome used to define productivity.

- It’s basic practice to make the assumed outcomes explicit.

- It’s better practice to justify the choice.

- It’s best practice to debate it openly and reach consensus.

Question 2: Have all the relevant outcomes that should been identified and taken into account?

Most interventions impact on multiple outcomes both for individuals and the system as a whole.

And many important outcomes can be felt beyond the individual patients in receipt of care. For example, good end of life care which may not extend life but ease the distress of the person dying and will also have important short and long term impacts for the patient’s loved ones.

And if the care has been poor, a bad death can cause upset, guilt and anger in families… a real disease… for years and even generations.

And not all outcomes are benefits. Longer life may come at the cost of impaired quality of life. Centralising a service may make access difficult for those who live far away.

An early discharge of someone still unable to care for themselves may prevent a caring family member from going to work. It’s also important to remember that there are many illnesses medicine cannot cure and that people have to live with and adapt to.

Even when medicine can’t cure it has much to offer in terms of supporting people through sometimes many years of less than perfect health. The humanity of care, bearing witness, helping people know they are not alone, the validation of the experience of illness and the value of life in general, being there, creating trust and the sense of being cared for are all highly valued by patients and their families.

In every age and in every society many of these ‘softer’ outcomes and the outcomes that are experienced by people other than the patient themselves are some of the most significant impacts of health care and heath systems.

These are often overlooked and difficult to measure but they still deserve to be taken into account.

In practice, when making system policy or service level decisions it’s often worth thinking explicitly about the outcomes that matter for

- individual patients

- their families,

- their community

- the population

- the health care system

- the wider economy and

- the environment.

Sometimes, you may decide some of these wider outcomes are irrelevant. More commonly, you will find that there are likely to be important outcomes that have not been thought about let alone identified, measured or valued that are relevant to the issues and decisions in question.

You will make better decisions if you find ways to taken these outcomes into account.

Question 3: What assumptions are being made about how those outcomes are generated?

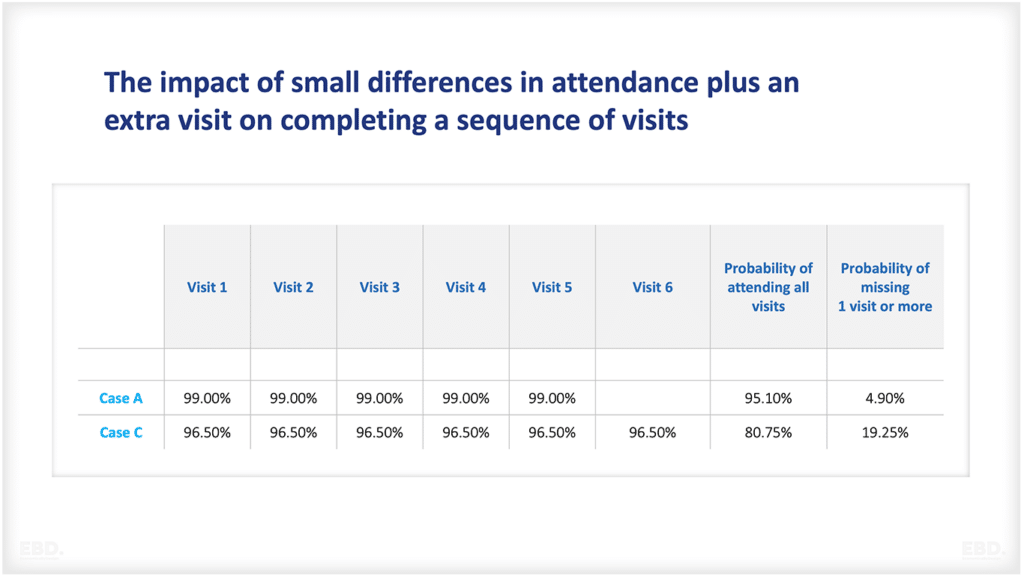

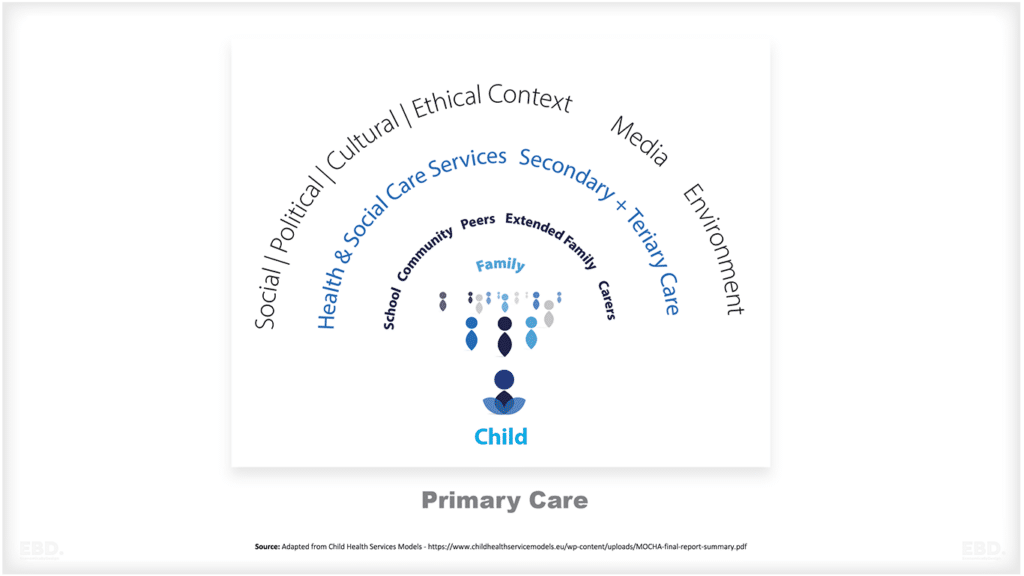

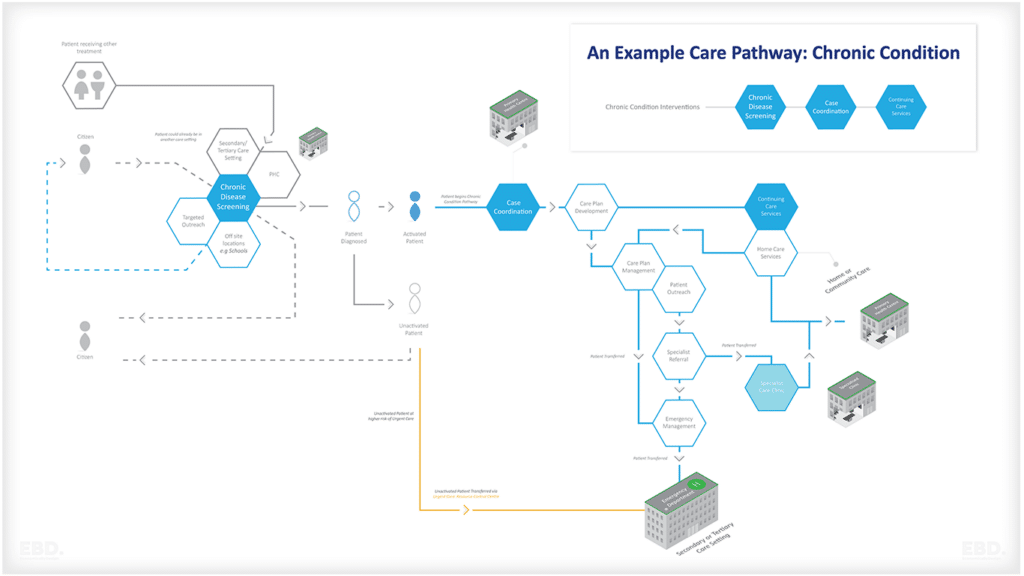

Just as most interventions have multiple outcomes, it’s also true that most outcomes people care about are influenced by multiple inputs.

The outcomes for an individual patient are not just the result of one element of care, but instead depend on the totality of care received from the GP, the physiotherapist, the pharmacist, the surgeon and more.

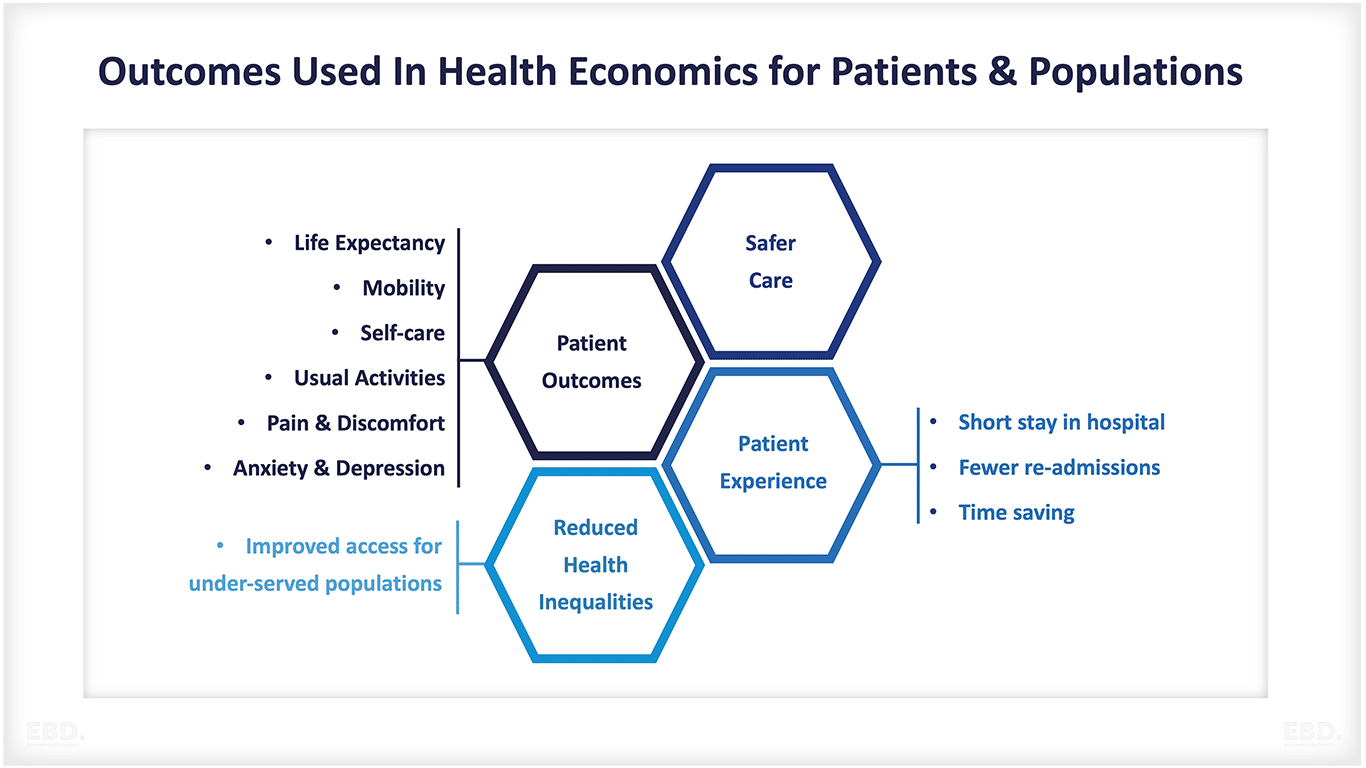

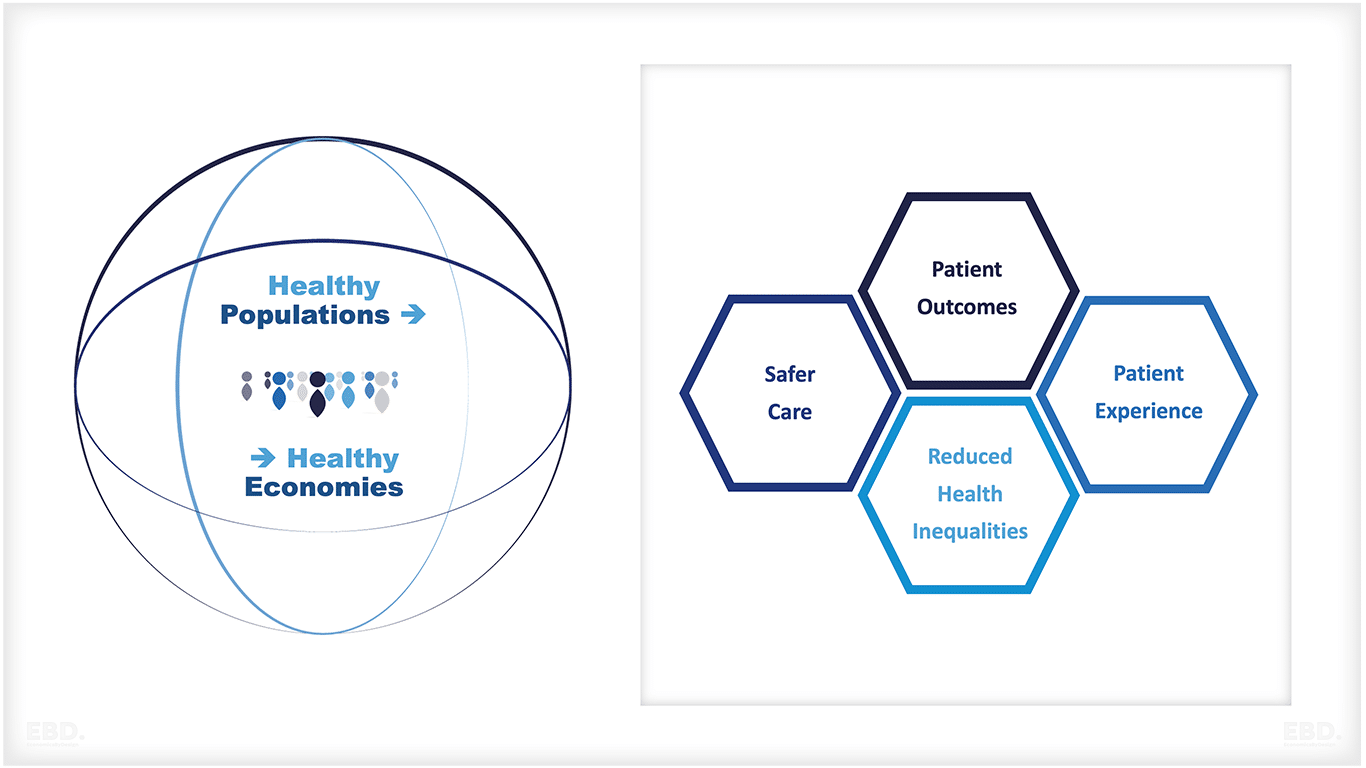

Often the interaction and relationships between the different elements of care are as important to the outcome as the specific elements of care themselves. And, if health (including length of life) and the distribution of health (i.e. health inequalities) are important outcomes for health care systems, then it’s important to know that the core determinants of health lie outside the health sector and consider how they can be influenced to improve outcomes.

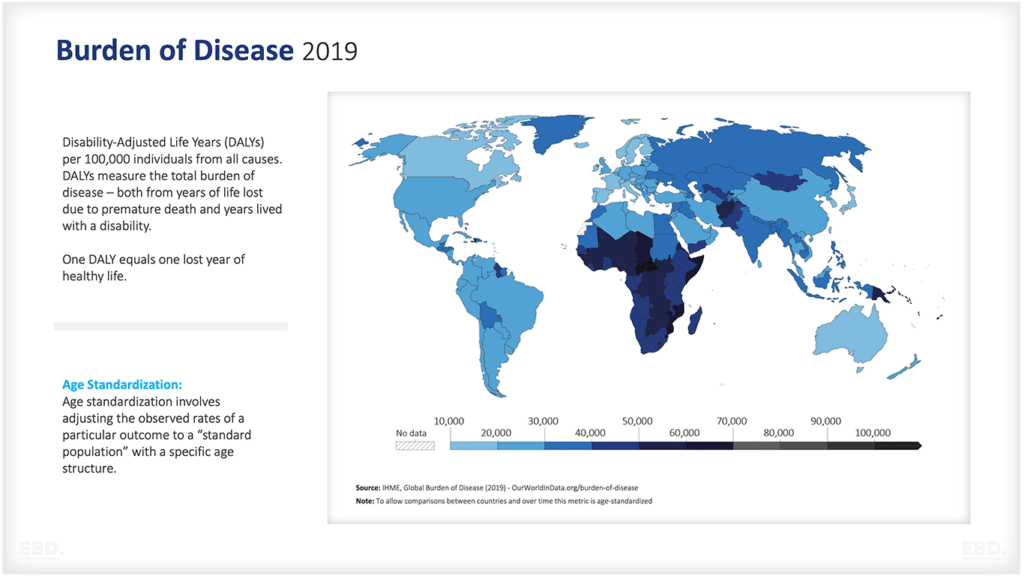

Poverty, housing, employment, nutrition, education, air quality etc all have a bigger impact on population health than traditional health care. In these circumstances attributing a specific element of care to a change in a specific outcome is often difficult if not impossible. Identifying contribution rather than attribution is much easier.

The characteristics described above i.e. that each outcome is influenced by multiple inputs, each input influences multiple outcomes, the interaction between inputs being significant and context specific – are the hallmarks of complex adaptive systems.

Increasingly, the best ways to shape the behaviour of complex adaptive systems are recognised as being different from the methods that work to control the behaviour of complicated but predictable machine-like production processes.

In a complex adaptive system it is important to

- be clear about the overall goals

- make sure everyone understands what they are

- align incentives for individuals, teams and organisations with those goals

- work to create the conditions in which front line staff can adapt their work to their specific circumstances.

By contrast, the tight performance management of detailed process targets stifles innovation, distorts priorities, generates multiple unintended consequences which ultimately make it more difficult to meet the overall goals for individuals and the system goals as a whole.

Question 4: What outcomes are you really trying to achieve?

When using economic analyses, as well understanding the outcomes implicit in the analyses being used, you also need to decide if those outcomes are actually the ones you want to be achieving. Often that may not be the case.

And as we have seen the outcomes of health care are many and widespread, and the core determinants of health lie beyond clinical practice. Again, when thinking about the system goals it’s worth thinking about the outcomes that matter most.

And in doing so, it’s likely you will find it’s impossible to optimise for everything at the same time, and that trade-offs are required. Working out what those trade- offs should be involves value judgements. Agreeing what they are is as much a political as a technical process.

Question 5: Can the most important outcomes be measured and valued?

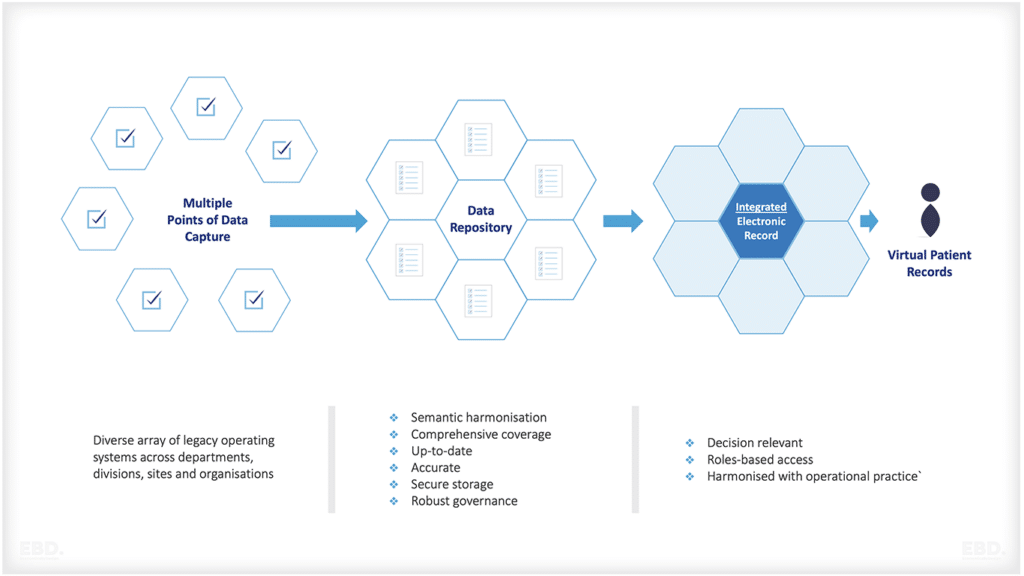

There are many important health outcomes that can be and are measured. Death is a good example.

Analysis of mortality data generates enormous amounts of valid, relevant and actionable information. It comes in many forms including expectation of life, age specific mortality rates (including neonatal and infant mortality), years of life lost, excess mortality, avoidable mortality, preventable mortality, mortality amenable to health care, cause specific mortality and more.

Increasingly other health outcomes such related quality of life, patient experience and patient reported outcomes are collectable. In practice it’s rare that full relevant outcome data are available.

That means decision makers have to make value judgements about outcomes, extrapolating beyond the available quantitative data.

Question 6: What ethical considerations should be taken into account in trading off outcomes?

There are almost always implicit ethical implications in decision making and in the information presented by decision support tools including economic methods and analyses.

This applies for tools designed to support decisions about the care of individual patients and those designed to support decisions about populations and systems.

A clinician’s job is to optimise for each patient up to the limits set by the laws and regulations of the system they work in and the resources at their disposal.

The outcomes that matter most may vary from patient to patient so part of the art of clinical practice is to build a relationship with each patient in which the patient is able to accurately share their priorities.

At system level, goals may be utilitarian (i.e. achieve the greatest good for the greatest number e.g. increase average life expectancy), they may also focus on social justice (e.g. reducing health inequalities) and c) promoting individual autonomy (e.g. by promoting choice). These goals are almost always in tension.

Optimising for only one of utility, justice or autonomy leads to suboptimal outcomes for the others. For example, achieving the greatest good for the greatest number might be achieved by ignoring the hardest to reach as it’s more expensive to provide them with care and by reducing choice for everyone.

In practice, either overemphasising any one of utility, justice or autonomy or ignoring any of them, will produce a pattern of care that is judged by the majority as suboptimal.

Transparency improves accountability – at the level of the individual make the patient’s ambitions explicit and when making decisions at system or population level be explicitly about the expected impacts on autonomy, social justice and utilitarianism.

Using health economics to add value

The outcomes of health care are many and various and accrue to many different stakeholders. Outcomes are sometimes obvious – the relief of pain, the restoration of function, the delay of death.

Often, they are less obvious – a sense a security, of trust, of peace, of well-being, a more economically productive economy.

The outcomes are experienced not just by individual patients, but their families, communities and the whole of society. The relationships between individual health and well-being, population health and health care are complex.

Health care contributes to health, but the core determinants of health lie beyond clinical practice. And many of the outcomes individuals and society as a whole care most about are the products of messy unpredictable complex adaptive systems rather than tidy predicable machine like systems.

Outcomes are central but often implicit to the application of economic methods. I argue we will get more value from economic tools and analyses if:

- We think broadly about the outcomes of health – both in terms of their nature and to whom they accrue

- We are clear about the outcomes we really want from health and care systems

- We recognise that many important outcomes of health care systems and not identified, measured or valued

- We factor in the unmeasured outcomes as well as the quantified outcomes in our decision making

- We recognise trade-offs and the value laden and ethical implications of the decisions we need to take

- We recognise that often there are no single right answers and that transparency and open debate is our best form of accountability.

Economic approaches to improving decision making in health care are likely to be of greatest value when they are combined with an understanding of the multiple consequences of a health system in society and the nuances of clinical practice.