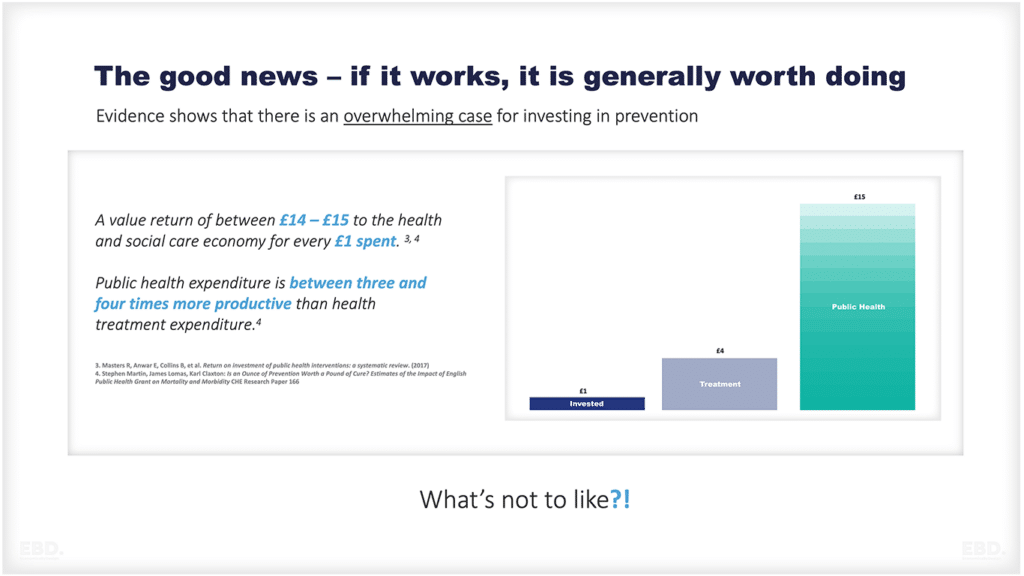

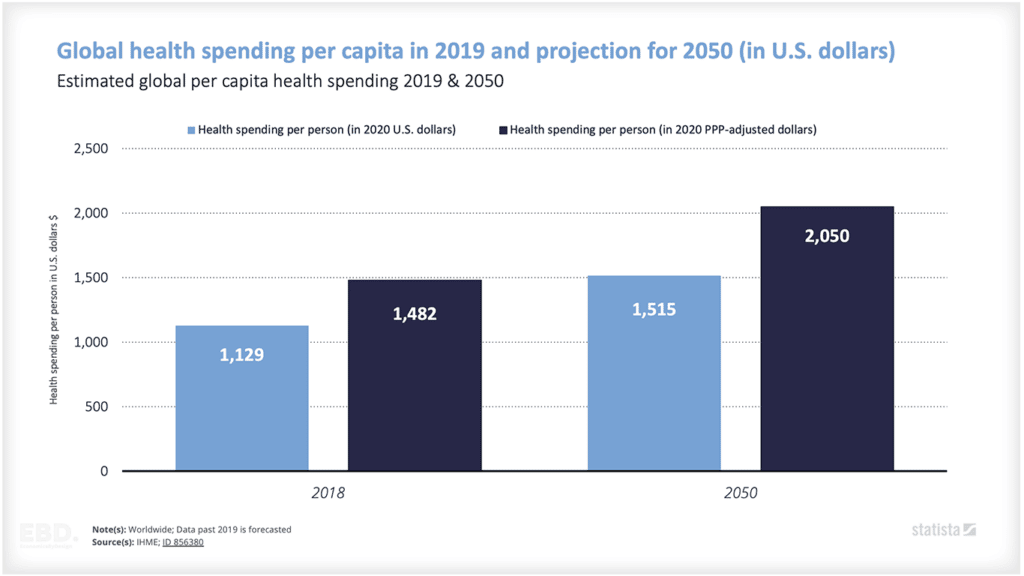

Spending money on effective ill health prevention programmes provides great value for money

Studies suggest that every £1 spent on preventative healthcare generates a £14 – £15 return to the health and social care economy and that public health expenditure is between three and four times more productive than health treatment expenditure [1],[2].

Preventative healthcare programmes, that generate revenue, are of significant potential value for governments and society.

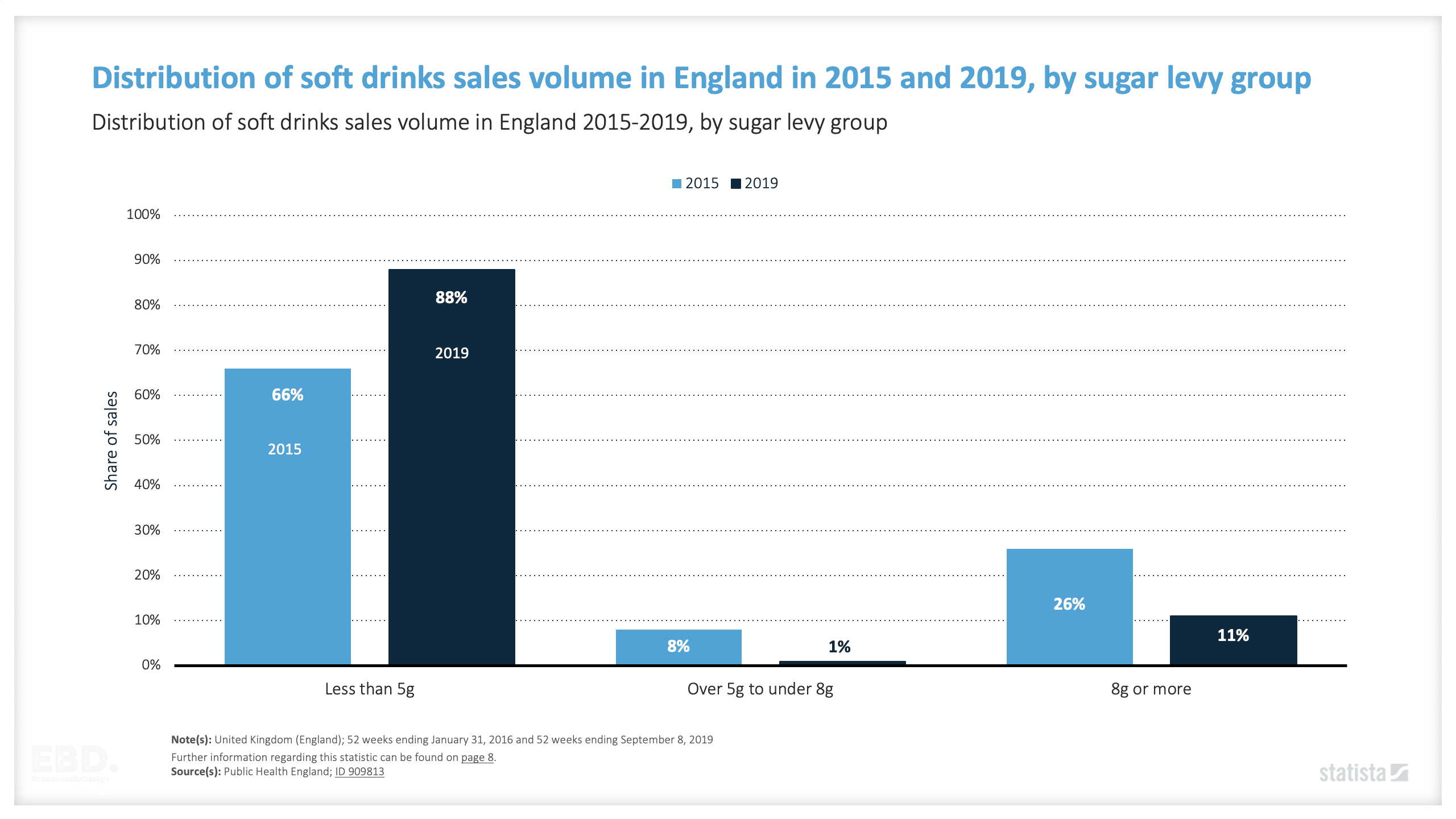

By imposing a tax on substances like sugar, salt, alcohol or tobacco, food producers and consumers will switch to other healthier alternatives. This should reduce their risk of contracting lifestyle related diseases such as diabetes or chronic heart disease. In turn this should increase healthy life expectancy which also has a positive impact on the economy [3].

To the extent that consumers don’t change their behaviour, tax revenue will be generated for the government to fund (in part) public health programmes more generally.

There is plenty of evidence to show that these types of policies do reduce consumption of harmful products.

The World Health Organization cites tobacco tax as one of the most effective and cost-effective interventions available to governments to promote health and wellness [4].

In practice though, the economics of this are a little more complex.

If the market for the affected product is highly competitive, or consumers are inclined to switch to other products even where there is a small increase in price, producers will not be able to pass the tax to consumers.

Much of the tax burden will fall on the producers and will increase the costs they face and reduce their profit margins. This will reduce the size of the market as less profitable companies close down, or move their focus to other products or economies with more related tax regulations.

Some producers will mitigate the effect of the tax by finding cost-effective alternatives to the taxed substances, such as artificial sweeteners to replace sugar.

These producers will continue to provide consumers with a version of the product, albeit with tighter profit margins.

In these circumstances:

Consumer prices may well still increase, which should impact on consumer behaviour;

Government tax revenues from the policy will be positive;

There will be short adjustments to industry and the labour market and hence to the contribution these products make to the economy;

In the long-term, improved healthy life expectancy will generate net additional economic growth[3].

If the market is less competitive, or consumers are relatively unresponsive to price increases, much of the tax burden will fall on consumers. Consumers will still consume the product, they will just pay more.

Still, the tax revenues of the policy will be positive. Industry will be largely unaffected. But the longer-term opportunities to improve healthy life expectancy will be limited.

Either way, the tax is regressive. Consumers in lower-income groups will pay disproportionately more of their income in tax than higher-income consumers.

This could have a negative impact on health inequalities. For products where markets are less competitive, or consumption is not so responsive to price increases, health inequalities could widen still further.

The evidence suggests, on balance, these taxes are a good thing for public health

A recent article reviewing the global evidence on sugar sweetened beverage tax reported significant evidence that such taxes reduced consumption significantly [5].

The evidence of the impact of these taxes on health inequality is more complex. The authors report the potentially regressive nature of these taxes. But, they argue this negative impact is offset if you consider that the risk of these chronic diseases is also highest amongst low-income groups.

Furthermore, if the revenues from these taxes are reinvested in other complementary efforts to reduce health inequalities, such as improving access to community leisure services, this can also mitigate the impact on low-income groups.

Whilst there is a paucity of actual evidence of the longer-term impact of sugar sweetened beverage tax on health inequalities, the same article does reference the evidence relating to tobacco tax.

Here the evidence is that any short-term impact on income is more than offset in the longer-term because of the reduction in risk of disease and associated health costs and income loss [6]. The same should apply to sugar sweetened beverage taxes.

In practice, the impact of introducing a tax on harmful products is likely to be a little different depending on the tax and the affected consumer markets. A tax on sugary drinks will be different in impact to a tax on sugar as an ingredient in processed foods.

It’s worth taking a little time to think through the potential complexities of these policies, and how to reduce the risk that they may inadvertently increase the gap between the health of low and high-income families.

[1] Masters R, Anwar E, Collins B, et al. Return on investment of public health interventions: a systematic review. (2017)

[2] Stephen Martin, James Lomas, Karl Claxton: Is an Ounce of Prevention Worth a Pound of Cure? Estimates of the Impact of English Public Health Grant on Mortality and Morbidity CHE Research Paper 166

[3] /spring-2022-forecast-statement/

[4] //www.who.int/activities/raising-taxes-on-tobacco

[5] Petimar J, Gibson LA, Roberto CA. Evaluating the Evidence on Beverage Taxes: Implications for Public Health and Health Equity. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2215284. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.15284

[6] Chaloupka FJ, Powell LM, Warner KE. The use of excise taxes to reduce tobacco, alcohol, and sugary beverage consumption. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:187-201.