Introduction To Climate Change, Climate Mitigation + Climate Adaptation

Climate change is now a well-known, broadly recognised and politically contentious phenomenon that is taking place across the globe. As such it is set to have major implications for humanity for centuries to come.

The key issues concerning climate change are how we, as humanity, respond to the challenges.

Basically, this comes down to actions to try to stop global warming (climate mitigation) and actions to deal with the consequences of global warming (climate adaptation). The reality is that both of these have large scale cost implications and will have significant impacts on country economies.

Much has been written and discussed about mitigation but a lot less about climate change adaptation.

In this economic lens I wish to consider the cost implications of climate change adaptation in the United Kingdom and how it might be financed.

See other climate related articles by EBD The Health Economics of Climate Change + The Economics of Climate Adaptation

What causes climate change?

The primary cause of climate change is global warming which manifests itself as an ongoing rise in the average surface temperature of the planet along with corresponding rises in the oceans and the atmosphere.

Data from the Met Office shows:

- A roughly constant average temperature in the late 19th century.

- A rise in the early 20th century.

- A levelling off or slight decline in the mid-20th century.

- A steep rise in the final decades of the 20th century, continuing into the 21st century.

Global warming not only drives climate change but also contributes to various critical weather-related impacts. These include an increased frequency of extreme weather events, such as floods, wildfires, heat waves, and droughts, as well as longer-term stressors like sea level rise and heat stress.

The consequences of these impacts are significant, leading to environmental issues such as loss of biodiversity and habitat destruction.

What causes rising temperatures?

The rise in temperatures is primarily a result of the imbalance between the solar energy received by the Earth from the sun and the energy radiated back into space as infrared radiation.

When these two factors are in equilibrium, the Earth’s temperature remains relatively stable. However, over the past two hundred years, particularly since the onset of industrialisation, the burning of fossil fuels—such as coal, oil, and gas—has significantly increased the emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs), including carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and water vapour, into the atmosphere.

These emissions create a “blanket” around the Earth that does not affect the incoming solar radiation but restricts the escape of infrared radiation.

As a result, the energy inputs and outputs become imbalanced, leading to an increase in the Earth’s temperature.

Consequently, we can be certain about two things

- The temperature of the Earth is rising and has been rising for many years

- These temperature rises are caused by the activities of humans rather than natural causes.

Scientists now refer to the current geological age as the anthropogenic age meaning the first period during which human activity has been the dominant influence on climate and the environment.

What is the world doing about climate change?

For several decades there has been an increasing focus on the issues of climate change at local, national and international levels. This has been led and facilitated by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) secretariat. Scientific support is provided by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) which undertakes a huge amount of research climate related issues.

Nearly every year since 1997, parties to the convention meet at a Conference of the Parties (COP). At these events, countries discuss the situation regarding climate change, take decisions and make pledges about what should be done.

There are two pivotal United Nations climate change targets which must be achieved to avoid ongoing global warming with severe consequence. These are:

- Net zero – to achieve a situation of there being net zero emissions of GHG by 2050.

- Global surface temperatures – to contain the rise in the average temperature to 2.0°C but preferably 1.5°C. These rises relate to global temperatures pre-industrialisation.

Clearly a huge amount of time and resources have, and are still being, committed to international climate change and there have been some big achievements in relation to the Kyoto Protocol and the Glasgow Climate Pact. However, there are still many concerns around the pace of action, a lack of engagement by some countries and a failure by countries to provide funds to meet certain pledges which require finance.

What the four main barriers to achieving global climate targets?

I am strongly of the view that the world will fail to meet the twin targets of net zero by 2050 and a rise in global surface temperatures of 1.5°C.

My four main reasons are as follows:

1: Escalating temperatures

The world is already close to the 1.5°C surface temperature rise. Temperatures have already risen by 1.2°C since the start of industrialisation (the benchmark) and it is anticipated that there is a 50% chance that 1.5°C limit will be breached in the next five years.

2: Concentration of GHG Emissions

Analysis of available data shows that getting on for almost 70% of global GHG emissions derive from just ten (out of 197) countries. These “top ten” countries, in order of pollution levels, are: China, USA, India, Russia, Japan, Iran, Canada, Germany, Saudi Arabia and South Korea.

These countries show a mix of political structures (e.g. democracies, monarchies, theocracies). Some are major industrial economies while others are major fossil fuel producers which rely heavily on oil and gas revenues.

The key point here is that the predominance of these ten countries in terms of GHG emissions means that if they do not take appropriate climate change mitigation actions, the impact of other country actions will be negligible.

3: Insufficiency of climate mitigation actions

The extent of climate change mitigation efforts of these “top ten” polluting countries has been sorely lacking. All of these countries have been described as having climate change mitigation efforts which are deemed insufficient, totally insufficient or critically insufficient.

4: Tensions between countries

Many of these countries have, today and in the past, had serious conflicts and/or tensions with one another. Levels of trust between them are low. This would seem to inhibit cooperation on climate change.

At this point it is useful to mention an example drawn from game theory entitled “The Prisoners Dilemma”.

According to game theory, and in particular the prisoner’s dilemma, rational individuals might not cooperate with each other even though it would be in their combined best interests to do so. By prioritising their personal interests, individuals acting rationally can create a worse overall result. The key here is how much trust exists between the parties.

In the light of this, some countries may wonder about the wisdom of continuing climate change mitigation actions at current levels when such actions will be expensive, may seriously damage a country’s economy and significant climate change may happen anyway.

Take for example Australia which produces 7% of the worlds coal output. Discontinuing coal production would have a huge impact on the Australian economy and, if other countries continue to mine coal at existing or higher levels (which they might do) then it will be all in vain for Australia.

What top 10 challenges will humanity face if climate change targets are missed?

Given a failure to achieve the targets set, it is likely that there will be substantial challenges facing humanity including the following:

- Record high temperatures

- Record low temperatures

- Stronger storms

- Shrinking sea ice

- Desertification of land

- Coastal flooding

- Famine

- Drought

- War

- Mass migration

This is not a pretty picture for the future. In rich countries, life will become difficult and uncomfortable for many. Traditional habits/lifestyles may change. However, in poorer countries, the results may be catastrophic.

Climate change mitigation and adaptation: What are the costs?

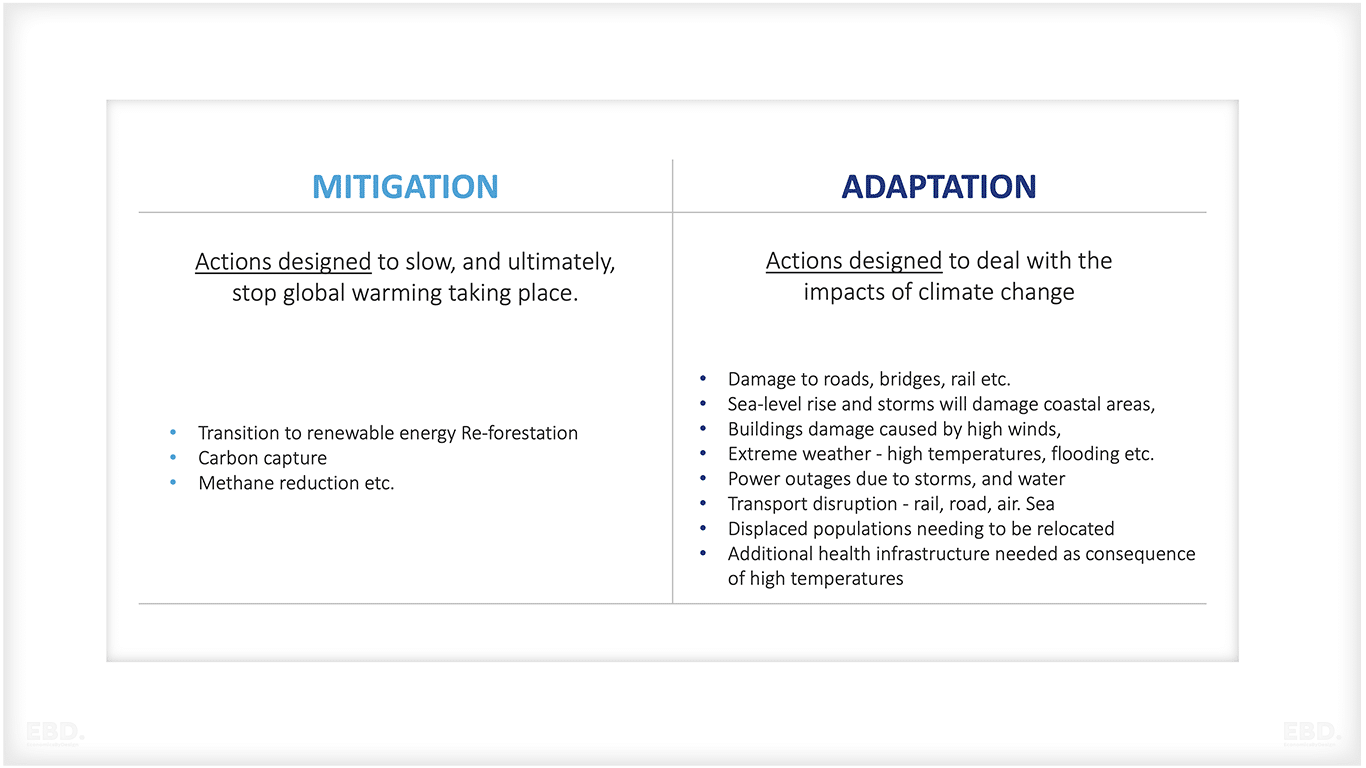

Climate change actions can be broken down into two main types – mitigation and adaptation.

The distinction is shown in the table below:

Spending on climate change mitigation

Turning first to the costs of mitigation the current/historic costs of UK mitigation are difficult to ascertain. In 2019, the UK government committed to provide £11.6bn between 2021 and 2026 for financial assistance to developing countries.

The Office for Budget Responsibility reported in 2021 a total of £25.5bn between 2021-22 and 2024-25, rising from £4.4 billion per annum to £7.7 billion in 2024-25.

Firm data appears to be lacking for the private sector. While many companies incorporate climate change mitigation into their operations, this spending is often not categorized as climate mitigation expenditure.

The private sector is urged to invest more in mitigation for several reasons: potential long-term cost savings, enhanced customer perceptions, and a meaningful contribution to combating global climate change.

Spending on climate change adaptation

When we consider climate change adaptation, the reality is that the historic expenditure is either limited and/or difficult to estimate because it isn’t classed as climate change related.

Costs of climate change to the UK

Considering the potential costs of climate change in the UK, the figures are quite concerning:

The European Environment Agency

Estimates suggest:

- A temperature rise of 1.5°C could lead to costs of €40 billion annually.

- For a rise of 2°C, the costs could escalate to between €80 billion and €120 billion each year.

The UK would account for approximately 10% to 15% of these estimates.

Co-designing the assessment of climate change costs (COACCH)

COACCH projects that by 2045, the financial impact of climate change on the UK could reach at least 1% of GDP, translating to £20-25 billion.

The UK Climate Change Committee (UKCCC)

The UKCCC indicates that adaptation costs could exceed £10 billion per year during this decade, with significant increases anticipated in the coming years.

So where would this leave the UK in relation to future expenditure on climate change actions. I suggest that while a single definitive cost for UK adaptation isn’t available, available evidence suggest it could be several tens of billions annually and this will increase, possibly substantially, in later years and as global temperature rise and exceed 1.5°C. The mix between costs falling on the public and private sector respectively is unclear.

So, can we afford to continue financing mitigation at current levels in addition to the financing the costs of adaptation which are enormous? This question is especially pertinent if we think (as I do) that the world will not achieve the climate objectives set by IPCC.

How do we finance the costs of climate change adaptation?

Six contextual factors

We need to look at the context in which the financing of climate change adaptation must be set.

The following six factors seem key ones:

- Public Debt – High levels of UK public debt and (arguable) unsustainable global public debt.

- Economic Growth – UK (and other country) economic performance has been sluggish for many years, which has implications for public finances. The new government is placing great emphasis on higher economic growth, but it remains to be seen if that takes place.

- Aging populations – impacts on demands for health and social care services, and the supply of labour to the UK economy.

- Defence requirements – pressure to increase defence spending (as a % of GDP) in response to the international security situation.

- Health protection – as of September 2023, the cost to the UK government of the Covid pandemic is estimated at between £310 bn to £410 bn. There are still ongoing costs associated with Covid. However, the conditions under which the Covid virus developed still exist with the two major hypotheses being a natural zoonotic spillover. Hence, a new pandemic is always possible and protection arrangements ned to be in place.

- Asylum seekers – Home Office figures released in August 2023 showed that costs of running the UK asylum system reached £3.96 bn in the 12 months to the end of June 2023, up from £2.12 bn in the same period a year earlier, and more than six times the £631 mn in 2018 when the asylum backlog began to build. Hence, there seems significant cost to Government which will be ongoing.

Options for financing climate change adaptation actions

In the light of the above (and other factors) we have to seriously consider how the UK government might finance the adaptive responses required to deal with the impacts of climate change. Some options are outlined below:

Switches in public spending

The funds for climate change adaptation could be obtained by switching existing funding on various public services. However, a moment’s thought would suggest that this is just not feasible.

The scale of funds requires might lead to significant reductions in funding for large public expenditure programmes (e.g. the NHS) or the complete abolition of a smaller programme such as culture media and sport (£6bn).

Higher levels of general taxation

Clearly additional public funds cold be obtained by raising the tax rates of existing general taxes such as income tax, corporation tax, VAT and capital gains tax.

At the time of writing the main political parties are adamant about not raising tax levels to finance problems with existing public services and it seems unlikely they would do so for climate change adaptations.

Hypothecated tax

A hypothecated tax is one where the revenue from a specific tax is dedicated for a particular programme or purpose. This approach differs from the classical method according to which all government spending is done from a consolidated fund.

Hypothecated taxes are not common and are disliked by politicians and government officials as they reduce their control over the use of tax revenues. However, they are often regarded favourable by voters.

One approach might be to establish a hypothecated tax to finance the annual costs of climate adaptation. This would provide greater transparency for taxpayers.

Private finance schemes

The private finance initiative (PFI) was a procurement method utilised initially in the 1990s and which utilised private sector investment in order to deliver public sector infrastructure and/or services, according to a specification defined by the public sector.

It is strongly debated as to whether the PFI gave good value for money in the use of public funds, but the big advantage of the approach was that the public sector did not have to find the up-front capital finance needed to construct the infrastructure.

It does seem possible that some form of PFI approach could be developed to finance climate change adaptations in the future.

State owned investment fund

Many countries maintain funds that allocate financial resources for specific future purposes. In the UK, for instance, the national insurance fund finances various state benefits and supports the NHS.

Meanwhile, Norway boasts a sovereign wealth fund exceeding $1.6 trillion, generated primarily from its oil industry. A significant portion of this fund is earmarked for addressing climate change and diversifying the economy.

Consequently, the UK government could consider establishing a similar fund, making annual contributions to accumulate resources for climate change adaptation.

Conclusion

My general observations are that the bulk of the debate about climate change has been about mitigation with only limited discussion on the issue of adaptation.

Part of this may be wishful thinking that if we achieve the mitigation then adaptation won’t be an issue. There are two fallacies here:

- My view expressed above, suggest that the world will fail to properly mitigate climate change because of the inactions of the most polluting countries; and

- Much of the damage has already been done and there will be major adaptation issues based on what has already happened.

When we come to the costs of climate change, we see a number of estimates, all of which are of dubious accuracy. However, the common factors are that the amounts of cost are large and that, in addition, there will be significant impacts on GDP. Hence we need to think seriously about how these should be financed.

A final comment is whether we can afford the costs of mitigation and adaptation given that global mitigation Is likely to fail.

This is a controversial statement, but I do see examples of where individual governments, including the UK, are backsliding on mitigation pledges (such as not drilling form more oil or putting back the date for eliminating petrol/diesel cars) and I wonder if this is based on a view that mitigation is not likely to be successful internationally.

References & Sources

- Climate Action Tracker

- COACCH Project. Codesigning the assessment of climate change costs.

- Our world in data: GHG country emissions

- Stanford: Prisoners Dilemma.

- The Met Office: Global average temperatures

- UNEP 2022 Adaptation Gap Report

- UKCC. 2022. The Costs of Adaptation, and the Economic Costs and Benefits of Adaptation in the UK

- European Environment Agency. 2023.Assessing the costs and benefits of climate change adaptation clam

- LSE. What will climate change cost the UK? Risks, impacts and mitigation for the net-zero transition.

- Financial Times. Cost of UK Asylum System.

- The Origins of Covid-19 – Why It Matters (and Why It Doesn’t).

- World Economic Forum – These-are-the-worlds-biggest-coal-producers-2018